Cat 3, Cat 5, Major Hurricane: What does the jargon mean?

Meteorologist/Science Writer

Friday, September 14, 2018, 3:44 PM - With all eyes on Hurricane Florence, the flooding and damage already caused by it, and the potential impacts to come, there have been a lot of terms thrown around - hurricane, category, eye wall, intensification - so what, exactly, do all of these really mean?

'Tropical cyclone' is the blanket term for used by meteorologists and atmospheric scientists to describe all of these large, rotating storms that spin up over tropical ocean waters. Several other terms are showing up in forecasts and news stories, however - hurricane and tropical storm for activity in the Atlantic, and typhoon and super typhoon for the Pacific - depending on what region of the world these storms form, which country is doing the reporting, and how strong the storms get. Even with all the other possible factors involved in determining how strong they are (central pressure, rainfall, speed, etc), when it comes to which term these storms go by, it all boils down two things - the location, and the strongest sustained wind speeds in their core.

Editor's Note: This article was originally published on August 2, 2016. It has been updated to reflect news that has occurred since that time.

Specifically for storms in the Atlantic and eastern Pacific oceans:

When one of these cyclones is just in the process of developing, so it's just a collection of clouds (storming or not) rotating around a low-pressure centre, with no distinct spiraling or central eye, but with maximum sustained wind speeds measured at less than 63 km/h, it earns the term Tropical Depression. It doesn't yet earn itself a name, however. Every storm starts out this way, so technically there are several tropical depressions every year. Since the term that sticks with any particular storm is the 'highest' one it reaches, Tropical Depression Four, which developed to the central Atlantic on July 1, 2017 and dissipated well north of Puerto Rico two days later, is the latest example we've seen in the Atlantic.

Since they were mentioned, what do "maximum sustained wind speed" and "landfall" mean?

The exactly meaning of maximum sustained wind speed depends on which meteorological organization is reporting, but it is the strongest winds of the storm, averaged over a period of 1 minute (for the US National Hurricane Center) or 10 minutes (for the World Meteorological Organization). It's basically one of the easiest ways to measure the strength of a tropical cyclone (besides central pressure), and winds are used as a scale to rate these storms (see below).

Landfall occurs when the point at which the storm is rotating around (rather than the edge of the storm or even the eyewall) makes contact with the shoreline of some body of land.

This graphic of Hurricane Florence shows the storm making landfall in the Carolinas, on September 14, 2018.

Back to the storms themselves, though.

When a tropical depression becomes a bit more organized, takes on the more familiar spiral shape as the clouds rotate around the core, and the maximum sustained wind speeds are 63 km/h or more, it becomes a Tropical Storm. It's at this point that the storm earns itself a name.

Atlantic and Pacific storms around North America work off separate lists of names, which are set by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). Each list has 24 alphabetical names (they skip I and Q), which alternate between male and female names. Odd years start with a female name and even years start with a male name. Each year, the list changes, but the lists are recycled every six years. So, the first storm of 2017 was named Arlene, the second was Bret, the third was Cindy, and so on. For 2018, the first three names will be Alberto, Beryl and Chris, and a different list will be used for 2019, 2020, 2021 and 2022. In 2023, we will again start off with Arlene, Bret and Cindy. If there are more than 24 named storms in a year, forecasters switch to the Greek alphabet, so the 25th storm is called Alpha, the 26th is Beta, and so on.

The only time names change on any of the lists is when a storm is particularly deadly or costly. At that point, the WMO makes the decision to drop, or "retire", the name of that storm, and they replace it with another name starting with the same letter.

(RELATED: Curious about how weather works? Watch Weather Wise on The Weather Network's YouTube channel!)

The order in which storms take on a name depends on when they become a tropical storm. If three tropical depressions form in succession, but the third is the first to become a tropical storm, due to being over warmer waters and with less shear influencing its development than the other two, that storm will become the first named storm of the three, and will take on the next name in the list. The other two will follow, in order, if and when they actually strengthen to be tropical storms.

|

|

If a tropical storm still has warm ocean waters under it, to tap into as a source of energy, and the winds blowing across the top of the storm aren't driving too hard (ie: wind shear is low), it will grow stronger. When sustained wind speeds in the storm reach 118 km/h, it graduates to become a Hurricane. Technically, this branches off on its own scale, now, defined by what's known as the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale (SSHWS).

The weakest storm on this scale is considered a Category 1 Hurricane, with wind speeds of 119-153 km/h. By far the most common strength of hurricane, Hurricane Beryl (July 2018) was the last Atlantic storm to top out in this category, Hurricane Isaac (Sept 2018) also peaked at this strength, before slipping down into the Caribbean Sea and weakening to a depression, and this was the strength of Hurricane Earl when it hit Nova Scotia back in 2010. A Category 2 Hurricane, like Hurricane Juan in 2003, or the latest, Hurricane Helene, is one with peak sustained wind speeds of between 154-177 km/h.

Beyond these are the 'major hurricanes' - Category 3 Hurricanes, like Sandy in 2012, that have maximum sustained winds measured anywhere between 178–208 km/h, Category 4 Hurricanes, such as 2017's Harvey, 2018's Florence, and famous Hazel back in 1954, with maximum sustained winds between 209–251 km/h, and the true monsters, Category 5 Hurricanes, where maximum sustained winds exceed 252 km/h.

In our record-keeping, out of the hundreds of Atlantic storms we've seen, there have been only 33 that have reached Category 5. An excellent example of the devastation these are capable of is Hurricane Katrina in 2005, which was one of the five deadliest hurricanes to ever hit the United States, and the costliest natural disaster in the nation's history. While we had not seen a storm this powerful since Hurricane Felix, in 2007, both Hurricane Irma and Hurricane Maria both reached Category 5 in September of 2017.

Note: Although wind speeds are used to rank the category of a storm, a lower category storm is not necessarily less of a threat than one in a higher category. As we are seeing now, with Hurricane Florence stalled along the Carolina coastline, there is a potential for devastating flooding due to the combination of storm surge and sustained rainfall, even though the storm has now weakened to the point where it is only category 1.

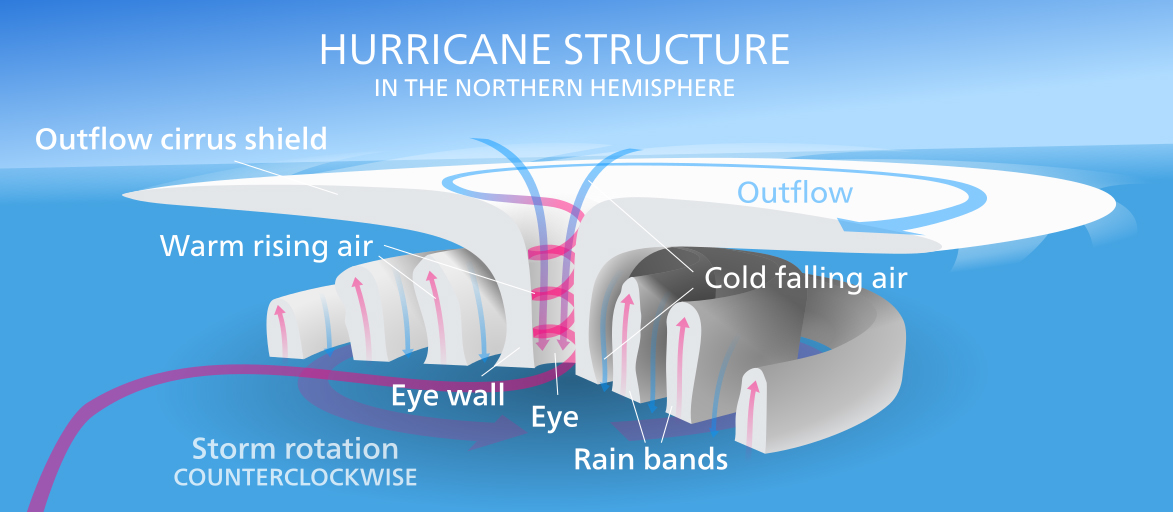

There is plenty of jargon when talking about the parts of a tropical cyclone, as well.

The most common term we hear is the "eye" of the storm, which is a region at the storm's axis of rotation that is characterized by warm air, light winds and a (usually) relatively clear sky. The eye is formed as air in the very core of the storm slowly sinks, which both suppresses cloud formation, and compresses the air, causing it to warm up. A close second is the "eye wall", which is the band of clouds directly surrounding the eye, which is usually the location of the most intense winds, and the strongest updrafts of air.

The structure of a hurricane. Credit: Kelvinsong/Wikimedia Commons

The "storm surge" associated with these cyclones is a swell of ocean water, caused by both the storm's winds and its low pressure, which is driven along ahead of the storm's core, and can cause severe flooding as that swell of water is pushed up into waterways and over land. Combine this surge with the normal ocean tide that is affecting the region at that time (either low, high or in-between), and you have the "storm tide".

As for their behaviour, the term "rapid intensification" refers to a storm's winds increasing by at least 30 knots (55 km/h) within a 24 hour period. One of the most extreme cases of rapid intensification we've seen is Hurricane Maria, currently in the Caribbean Sea, which strengthened from a Category 1 Hurricane to a Category 5 Hurricane in just over 1 day!

As mentioned above, the strength of a storm depends on how much energy it has available to it, and the ocean surface is the primary source of that energy.

For storms making their way up the U.S. east coast towards Atlantic Canada, like Arthur, the Gulf Stream supplies most of their energy. This warm ocean current hugs close to the east coast of the United States until it reaches North Carolina, and from there it flows on a fairly straight course to the northeast, out into the North Atlantic (shown to the right). The heat spreads out beyond this course, into the waters off of New England and past Nova Scotia, and the amount of heat that flows into these regions fluctuates, depending on shifts in the track of the main current, the time of year, weather patterns, and even climate change.

If a storm maintains a track along the east coast, exactly how long it maintains its strength typically depends on how warm the waters are off of New England. However, on its way, it will weaken any time it encounters land, due to friction with the ground and removal of its ocean energy source, or if it encounters cool waters, and it will strengthen again any time it moves back over warmer waters. This can cause the storm to change status - up and down between hurricane categories and even down to a tropical storm and back up to a hurricane again.

It's when the storm moves over a large tract of land or moves over persistent cool waters that it will quickly lose strength and status. It will scale back down through whichever categories it reached before that, until its maximum sustained wind speeds drop below 62 km/h. At this point, the storm becomes Post-Tropical, meaning its just a leftover remnant of a tropical cyclone, but it can still pack some very strong short-term wind gusts and significant rainfall.

There are two more terms that get used once in awhile, which are applied to storms that transition from one type to another.

Although the term Extra-Tropical Cyclone is used to describe your everyday standard weather system - typically shown on weather maps by a Low centre with a warm front and a cold front - a tropical cyclone can become extra-tropical if its vertical structure becomes more tilted. At that point, it no longer gets its energy primarily from below, but instead from the differences in temperature horizontally across the storm, it develops warm and cold fronts, and it typically joins up with any other frontal systems that happen to be in the vicinity. Hurricane Sandy went through this kind of transition just minutes before it made landfall on October 29, 2012, causing it to merge with a storm front that was moving in from the west, to become what one meteorologist called a 'Frankenstorm' - in honour of Halloween. As Sandy demonstrated, even when a tropical cyclone makes this transition, it can still be very powerful, continuing to pack hurricane force winds and enough moisture to produce heavy rainfall that can touch off major flooding.

The opposite situation to this is when a storm system moves from over land to over water and takes on a more vertical structure - like that of a tropical cyclone. This produces a Subtropical Cyclone. These can form much further north than tropical cyclones do, since these storms have colder temperatures at the storm's top, and thus don't need water temperatures quite as warm at their base to maintain their strength.