Antarctic's never-frozen Blood Falls has new explanation

Meteorologist

Sunday, April 30, 2017, 3:45 PM - Research has turned up a new answer for what makes Antarctica's Taylor Glacier weep ruddy tears.

The phenomenon - known as Blood Falls for its distinctive colour - was previously attributed to red algae from under the ice sheet, but a new study points to a different culprit.

Scientists have been investigating how running water flows from the 1.5 million-year-old glacier for more than 100 years, since the falls' discovery in 1911. The mean temperature of the surrounding air is an icy -17oC, sparking debate as to how regularly running water was possible at all.

Blood Falls. Photo courtesy Erin Pettit.

The research team, operating out of the University of Alaska and Colorado College, used radio echo sounding - sort of like a bat's echolocation - to track the origin of the water under the glacier and found a surprising result; a large source of salt water that may have been trapped under the glacier for more than 1 million years.

Their new study, released this week, pins the process on this pool of salt water - so salty they refer to it as brine - which dramatically lowers the freezing temperature, and the actual process of freezing itself.

If we take a brief trip back to high school science class, you might recall the molecules of liquid water have more energy than those of frozen water. In order to freeze, that energy must be released, as heat - known as 'latent heat of freezing'. "While it sounds counter-intuitive," study co-author Erin Pettit said in the team's press release, "water releases heat as it freezes, and that heat warms the surrounding colder ice."

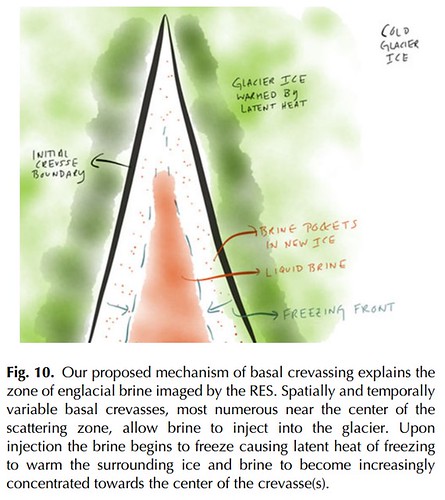

Salt-rich water is injected at variable cracks along the base of the glacier; water which then begins to freeze, releasing heat into the surrounding ice.

Image courtesy Journal of Glaciology.

When repeated, the process serves to concentrate the iron-rich brine which then flows from the ice in the macabre display known as the Blood Falls; their red colour the result of the iron 'rusting' (oxidizing) when it comes in contact with the air.

While the "Blood Falls" phenomenon is thought to be unique on the planet, the study gives a glimpse at how hydrological systems might work within other glaciers. "Taylor Glacier is now the coldest known glacier to have persistently flowing water," said Pettit.

Sources: Journal of Glaciology | National Geographic | University of Alaska Fairbanks |