How big was Comet PanSTARRS? A LOT bigger than expected!

Meteorologist/Science Writer

Tuesday, March 29, 2016, 3:03 PM - In late March, a newly-discovered comet made one of the closest flybys of Earth ever recorded for one of these dirty snowballs, and newly-released radar images have revealed that it is roughly ten times larger than originally thought!

On March 22, 2016, at just around 7 p.m. EDT (midnight UTC on March 23), Comet P/2016 BA14 (PanSTARRS) made a close pass of the Earth, at a distance of 3.6 million kilometres, or a little over 9 times further away than the Moon. This is now considered to be the third or fourth closest pass of a comet ever recorded.

When this newly-discovered comet was first discovered, it was producing a faint coma and tail and was fairly dim. It was also travelling along with another comet that we've known about for around 16 years now, named 252P/LINEAR, which flew past Earth at a distance of around 13 times farther away than the Moon just a day before, on March 21. The orbits of both comets are similar enough astronomers believe it's possible they may be two parts of a larger comet that broke up long ago.

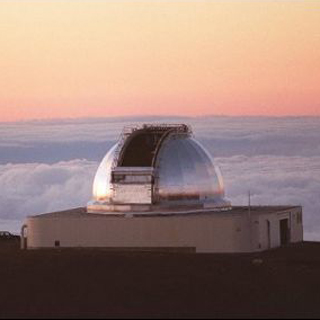

As Comet P/2016 BA14 (PanSTARRS) made its close pass, astronomers were not sitting idly by. They locked onto it with detectors at NASA's Infrared Telescope Facility (IRTF), located atop Mauna Kea in Hawaii, and radio dishes at NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory's Goldstone Deep Space Communications Complex, to gather as much information about it as possible.

|

|

|

What they found was surprising.

Original estimates of the size of P/2016 BA14 (PanSTARRS), based on its brightness as it approached, put the comet somewhere around 100 metres in diameter. Based on the observations by IRTF and Goldstone, the comet turned out to be much larger - more like 1,000 metres wide, or 10 times larger than originally thought!

Why this big discrepancy?

According to Dr. Vishnu Reddy of the Planetary Science Institute in Tuscon, AZ, figuring out how big a comet is depends not only on the brightness, but also on knowing how much sunlight the object reflects from its surface (its albedo). Assumptions are made when an object is first detected, based on the typical properties of comets and asteroids. Once the actual albedo is known - from combining optical and infrared observations - astronomers can get a better idea of the object's size.

Typically, the nucleus of a comet - its "dirty snowball" core - is darker than freshly-poured asphalt, reflecting only 2-3 per cent of the sunlight that falls on its surface. The coma - the cloud of gases that surrounds the nucleus while it's closer to the Sun - is much brighter.

|

|

So, since Comet P/2016 BA14 (PanSTARRS) was so dim to optical telescopes, the initial estimates included the assumption that a bright coma would be surrounding the nucleus, thus the nucleus itself was thought to be very small. As it turns out, though, this comet must be producing only a very small coma, so most of the light being reflected was actually from the nucleus.

Based on the infrared observations Reddy gathered of P/2016 BA14, he puts a range on the comet's diameter of between 600-1,200 metres. Since any size estimate from brightness and albedo includes some factor from the comet's coma, there is still going to be uncertainty using that method. As he wrote in an email to The Weather Network on Monday, "nothing beats radar direct measurement of the size."

"Radar signals can penetrate through the coma and allow us to look directly at the nucleus," Dr. Shantanu Naidu, the NASA JPL scientist who headed up the radar observations of P/2016 BA14, explained in an email. "The radar images resolve the nucleus into several pixels. From the number of pixels the nucleus covers in the radar images and from the size of each pixel we can get a very reliable size estimate of the nucleus."

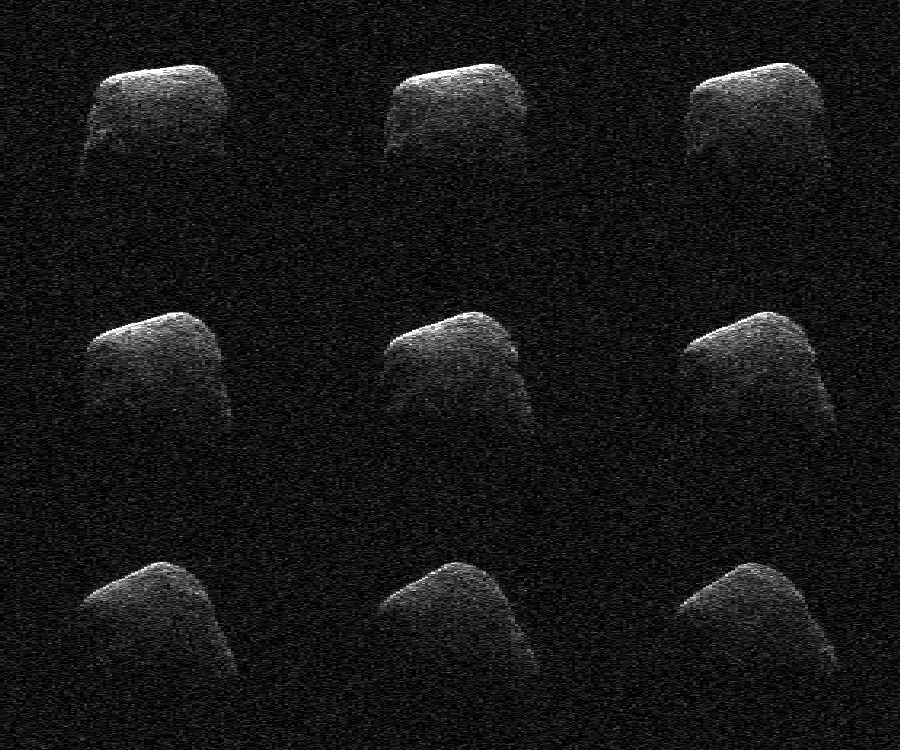

These radar measurements locked the nucleus in at a diameter of around 1 kilometre, and they also revealed the shape of the nucleus.

"The radar images show that the comet has an irregular shape: looks like a brick on one side and a pear on the other," Naidu said in a NASA press release. "We can see quite a few signatures related to topographic features such as large flat regions, small concavities and ridges on the surface of the nucleus."

Radar images captured by Goldstone on March 22, 2016, when the comet was roughly 3.6 million kilometres away. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/GSSR

A new relationship with 252P/LINEAR?

Based on the original 100 m estimate for P/2016 BA14 (PanSTARRS)'s diameter, which was roughly half the estimated size of 252P/LINEAR, one possible explanation for the similarity of their orbits was that 252P/LINEAR is a "parent" to P/2016 BA14. So, at some point in the past, for some reason, P/2016 BA14 broke off from 252P/LINEAR to take its own, slightly altered, path around the Sun.

With P/2016 BA14's diameter now coming in at ten times that initial estimate, and around three to four times larger than 252P/LINEAR, does this imply a different relationship between the two objects?

Dr. Jian-Yang Li, the senior scientist at the Planetary Science Institute, is in the process of analyzing one set of images of comet 252P/LINEAR, taken during its pass using the Hubble Space Telescope, and he has another set planned for the beginning of April.

"I can't say much about its size now, but it does look like BA14 is possibly larger than 252P," Li said in an email. "However, I do not think we can say one is the parent of the other, because their sizes are not too different. A better way is to say that they might be the fragments of a common parent object, if the link between these two objects is confirmed by further observation and analyses."

According to Li, despite their apparent size difference, 252P/LINEAR was discovered first because it is a more active comet than P/2016 BA14, and thus much brighter and easier to spot.

Sources: NASA Goldstone | Planetary Science Institute

![]() NOW ON YOUTUBE: Subscribe to The Weather Network's YouTube channel for access to the best weather-related videos in Canada VIEW THE CHANNEL | VIEWER VIDEOS | MOST POPULAR | SUBSCRIBE

NOW ON YOUTUBE: Subscribe to The Weather Network's YouTube channel for access to the best weather-related videos in Canada VIEW THE CHANNEL | VIEWER VIDEOS | MOST POPULAR | SUBSCRIBE