What a Prairies' fireball says about our space junk problem

Meteorologist/Science Writer

Monday, November 27, 2017, 6:17 PM - As residents of the Prairies witnessed a burning fireball pass overhead late Friday night, they were seeing the evidence of a growing problem around out planet - the increasing amount of junk that is littering space and what happens when it falls back to Earth.

At just around midnight, central time, over Alberta and Saskatchewan, a piece of flaming debris from space slowly tracked across the sky. The event caught the attention of some lucky local residents, some of whom noted that this was not a typical fireball.

A meteor fireball is the bright flash of light that results from a meteoroid entering Earth's atmosphere. These are pieces of ice or rock that have been floating around in space for a very long time, even going back to the birth of the solar system. These meteoroids travel at speeds of tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of kilometres per hour, so when they streak across the sky, they are typically gone in a matter of seconds.

Friday night's display was caused by something much, much younger, and something to be far more worried about - a rocket booster, which fell back to Earth after having delivered its payload into orbit.

The trajectory of the rocket as it burned up over Alberta and Saskatchewan. Credit: American Meteor Society

This particular rocket was the Antares booster that carried Orbital ATK's latest Cygnus CRS OA-8E cargo ship, named after NASA astronaut Gene Cernan, on a delivery mission to the International Space Station. Launched on November 12, 2017, the Gene Cernan is still birthed with the ISS at this time, and it is scheduled to leave the station on Dec 4, when it will release a number of cubesats before burning up somewhere over the Pacific Ocean.

The hardware that carried the Gene Cernan into orbit was up in space for just shy of two weeks, making several trips around the Earth, as one of the nearly 170 million pieces of space junk that have been accumulating since the late 1950s.

According to the European Space Agency (ESA), as of January 2017, there's an estimated 29,000 pieces of space debris in Earth orbit that are larger than 10 centimetres wide, 750,000 objects down to 1 cm wide, and 166 million objects smaller than 1 cm. From their records, the US Space Surveillance Network regularly tracks 23,000 objects.

For anyone or anything in space, any of this debris, even one of the millions of smaller bits, is most certainly a concern. A bullet, fired from a modern rifle, can cause enough harm as it travels at around 4,300 km/h. A similarly sized piece of metal from a spacecraft, though, such as one of the bolts that secured a satellite inside its rocket fairing, is travelling at speeds of around 27,000 km/h as it circles the Earth. If that bolt were to hit a satellite, or the International Space Station, or one of the astronauts while they're on a spacewalk outside the station, it could easily cause damage or even death.

Back in April of 2013, when Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield was commander of the ISS, he reported seeing a small hole in one of the station solar panels, due to some piece of debris.

It's unknown whether this was some natural meteoroid or a piece of artificial debris, but the result was the same.

Also, one of the windows of the space station's cupola, where the crew frequently take images of Earth, still sports a chip from a similar impact, as shown in this Tweet from ESA astronaut Tim Peake.

The concern over these impacts, and the potential for disaster from them, was explored by NASA scientist Donald J. Kessler in 1978. The Kessler Syndrome, named after him, is when the number of space debris objects grows so large that an impact between two objects results in a cascade effect. One impact generates a swath of smaller debris, which goes on to strike other objects, generating even more debris, which strike even more objects, and so on. The result of this could, potentially, destroy every functional satellite and spacecraft in low-Earth orbit, and could also make it impossible to successfully launch satellites afterward, until the debris was eventually thinned out by re-entry into the atmosphere (a process that could take decades). See the movie Gravity for a not-entirely-unrealistic example of this scenario.

Smaller bits of space junk are of little concern for those of us living on the ground. At the speeds they're travelling, they vapourize as they plunge through Earth's upper atmosphere, producing ordinary-looking meteor flashes. Even something larger is unlikely to reach the surface intact, since the atmospheric friction tends to break these apart into smaller and smaller pieces, which are then vapourized. Even if something larger did reach the surface, these objects usually fall over remote parts of the oceans, but this is not always the case.

On January 22, 1997, two pieces of a Delta II rocket second stage, which had launched into space nine months earlier, managed to survive re-entry to crash down in Texas.

|

|

|

Noone was hurt in either of these incidences, and according to NASA, not one person has been injured or killed by falling space junk in the decades we have been launching rockets into space. Still, if these two pieces had hit the ground in a more heavily populated area, they would likely have caused significant damage, and people in the vicinity could be injured or killed.

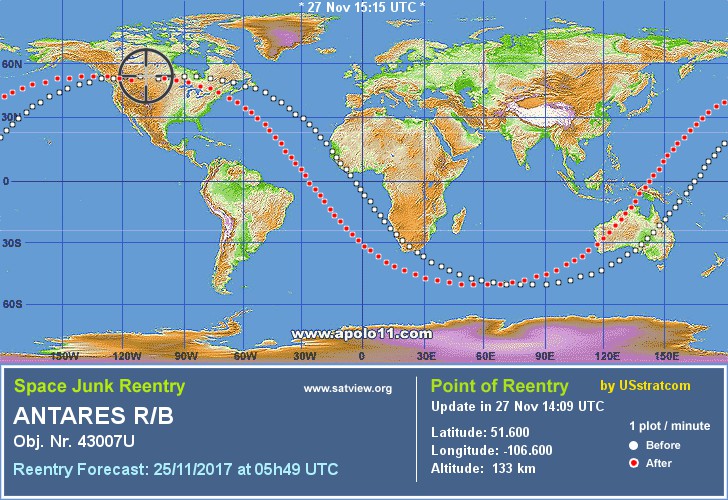

Websites such as Satview.org track these objects, as well as operational satellites and the International Space Station, and they issue forecasts for when orbital debris will re-enter the atmosphere.

Antares rocket body orbital track, and point of re-entry into Earth's atmosphere. Credit: Satview.org

According to that site, large objects enter the atmosphere once every week to two weeks. The next object of concern is China's Tiangong-1 space station, which is currently making an uncontrolled decent, and is expected to re-enter the atmosphere sometime in late March 2018. Satview's current forecast has Tiangong-1 splashing down somewhere in the western Pacific Ocean, however being off by only a few hours, either way, would put it over a vastly different part of the world. This forecast, and the projections of agencies monitoring it (including China's space agency), will narrow this down closer to the time of re-entry.

Re-usable rockets, such as SpaceX's Falcon 9, are one way to reduce the amount of space junk that accumulates, moving forward. SpaceX even has plans to make its satellite fairings (the clam-shell-like structure that surrounds and protects a satellite during launch) recoverable, and they may even pursue plans to make their second stage recoverable as well.

There are also plans being made for various technologies that could reduce the amount of space junk that is currently orbiting the planet. Proposals have suggested everything from satellites capturing pieces with nets or harpoons, to using lasers from ground stations to slow objects so that they fall out of orbit.

Sources: American Meteor Society | European Space Agency | Satview | NASA