Magdalen Islands' gravel shield against climate change

Hurricane Fiona hammered the Magdalen Islands’ already fragile coastline in late September. In the aftermath, we met someone working on solutions to shield the islands against the impacts of climate change.

Long before European settlers arrived, the Magdalen Islands were know by their Mi'kmaq name, which means "islands swept by the surf". It’s an apt description, as the archipelago’s famed red sandstone cliffs were literally sculpted by the waves and wind, eroding it into its ever-changing dunes and beaches.

Geographically situated in the heart of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, the archipelago is also at the forefront of climate change, but its inhabitants are resilient. In the field during Hurricane Fiona, MétéoMédia reporter Patrick de Bellefeuille met up with Jasmine Solomon, Coastal Erosion Project Manager for the municipality of Îles-de-la-Madeleine, to learn more about their interventions to protect the islands from rising seas and more frequent storms.

She identified erosion and flooding as the main threats to their coastline. Both are aggravated by global warming, which reduces the ice cover, an important barrier against the waves. More frequent and severe storms also accelerate erosion.

One major investment in climate change adaptation is called soft armoring, or beach refill. It’s a simple idea: the beach is eroding away, so we replace it. Traditionally, beach refill was done with imported sand (which just washes away) or large boulders, but here they are building a shield of gravel.

Smaller-caliber pebbles — also known as riprap — are dumped on the most vulnerable shores, creating steep rock beaches. Unlike larger rocks or seawalls that block waves but accelerate their energy, gravel dampens and absorbs them. This protects the more friable sandstone banks and cliffs.

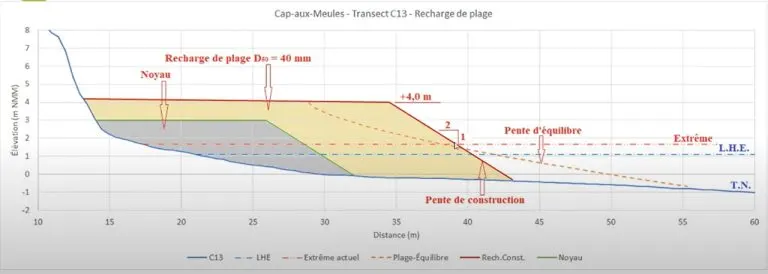

Schematics for the refill at La Grave (Source : Municipalité des Îles-de-la-Madeleine)

With our expert, we visited the Cap-aux-Meules refill, which was started last August to protect 857 meters of coastline at a cost of $11.6 million. Over a nucleus of island sandstone, they will deposit 103,000 tons of Nova Scotia gravel. A similar project was completed in 2021 to shield the historic site of La Grave in Havre-Aubert with 37,800 cubic meters of gravel from Newfoundland.

Fiona put the new gravel beaches to the test, and according to Solomon, it was a success. The gravel “reacted well” to the storm of the century. Without this shield, the roads and downtown core may have seen even more damage.

“It really protected a good part of La Grave. The idea is that the waves penetrate the rock and are absorbed, and that's what happened,” she told MétéoMédia. “We are really happy that it was there, because I think we would have seen much more damage.”

Soft armoring protects key island roads like this one (Source: MétéoMédia)

Extending the gravel shield to the whole island would be impractical, given the astronomical cost of importing tons of rock from the continent. The experts on Solomon’s team have prepared an intervention plan that targets the most vulnerable sections of the coastline, based on the funds available.

“Madelinots have gone through many storms and hardships. Whether it's Fiona or Dorian or the ice storm, we always have this feeling that we'll get through it,” said Solomon. “But I think mentalities have changed a lot over the past decades. People here are increasingly aware of climate change, they observe it more and more. When you lose meters of your yard every year, you tend to be much more alert to climate change.”

With files from Patrick de Bellefeuille. Header image: the natural stone beach at Entry Island, Magdalen Islands (source: Patrick Donovan/Getty Images)