Tropical cyclones decreased last century as global warming sped up

Compared to the past, fewer tropical cyclones are spinning up around the world, but that does not diminish their danger.

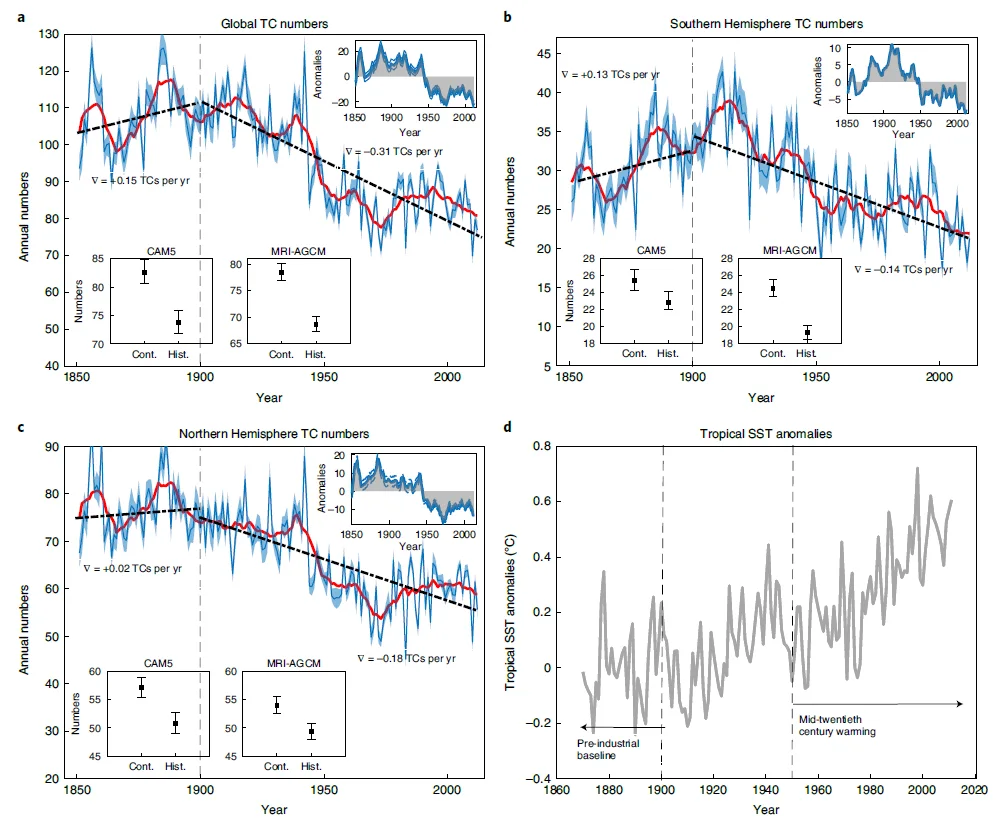

A new study shows that as the world warmed throughout the 20th century, there was a significant decrease in tropical cyclones seen in all but one of the world's ocean basins.

How are global warming and climate change impacting tropical cyclones? Researchers have been trying to answer this difficult question for years. One of the hurdles they face is the sparseness of records from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Without satellites and worldwide systems of weather reporting, it was possible to miss entire storms that were not witnessed by ships or that did not come near land.

In recent years, 'climate reanalysis' has become a valuable tool in this field. By running sophisticated climate models using actual past data, researchers can accurately reproduce past weather events.

Applying this to tropical cyclones, climate reanalysis uses our modern understanding of how these storms form and affect the weather around them, to look at past weather records from land and ships. The results can then tell us what the total number of storms likely was — the ones we already know about from historical records and those that likely occurred but were not witnessed by anyone.

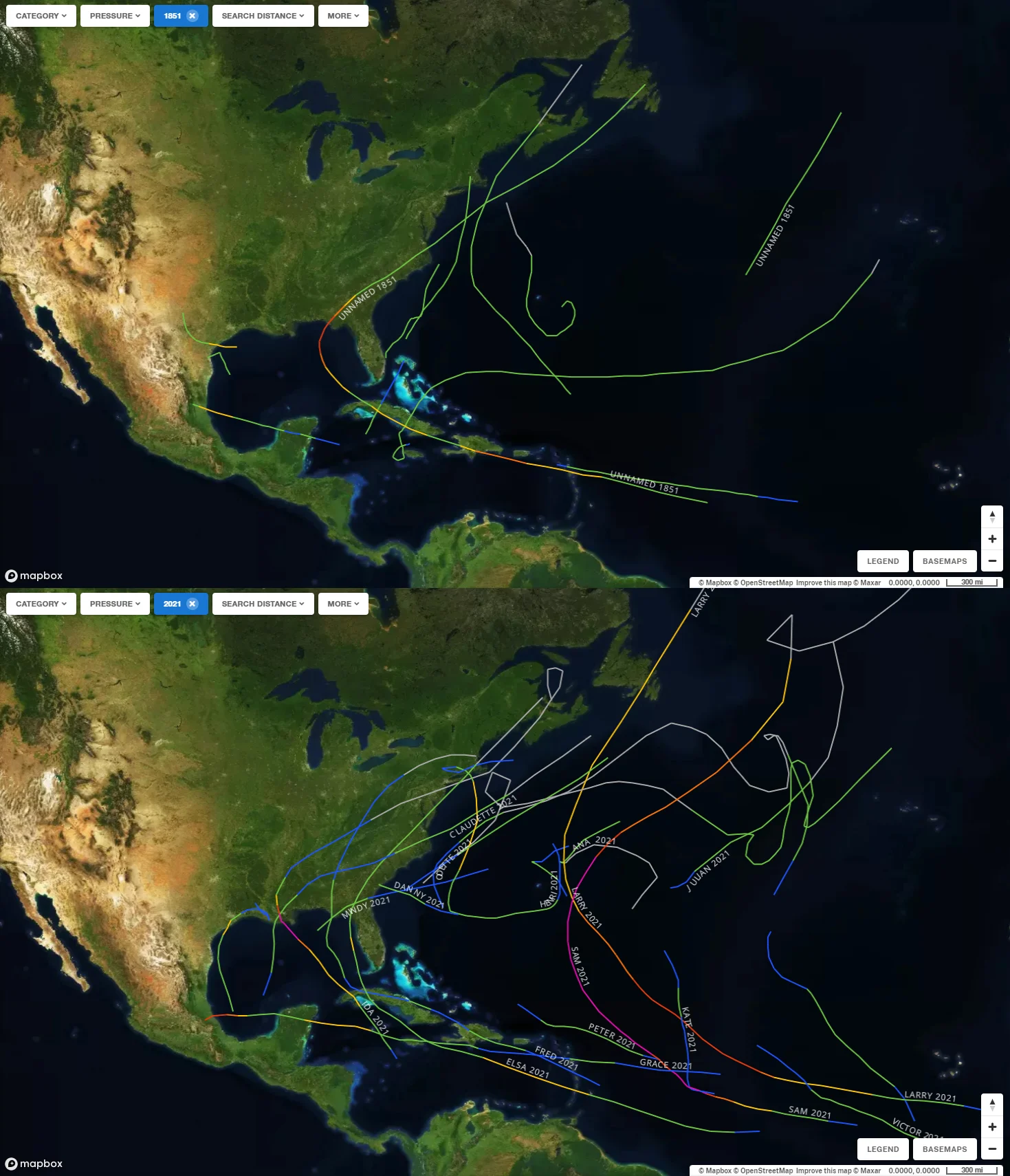

North Atlantic hurricane tracks from NOAA’s official records, from 1851 (top) and 2021 (bottom). Although there are only 13 storms on record from 1851, compared to 21 in 2021, the lower number is likely due to several storms being missed because they were not witnessed by ships and did not make landfall. (NOAA Historical Hurricane Tracks)

Last December, research out of MIT used climate reanalysis to show that the number of tropical storms and hurricanes in the North Atlantic Ocean had increased throughout the 20th century.

A new study by an international team of scientists has confirmed that trend. However, at the same time, it has also revealed a decrease in the number of tropical cyclones in the rest of the world. This includes eastern Pacific hurricanes, western Pacific typhoons, and south Pacific and Indian Ocean tropical cyclones.

"For most tropical cyclone basins (regions where they occur more regularly), including Australia, the decline has accelerated since the 1950s," Dr. Savin Chand, the lead author of the new paper published in Nature Climate Change, wrote in an article on The Conversation. "Importantly, this is when human-induced warming also accelerated."

Global tropical cyclone numbers, reconstructed from the 20th Century Reanalysis dataset, from 1850 into the early 21st century. Globally this study found a 13 per cent reduction in the number of tropical cyclones while tropical sea surface temperatures (lower right) increased. (Chand, et al., 2022)

"The only exception to the trend is the North Atlantic basin, where the number of tropical cyclones has increased in recent decades," Chand explained.

Both Chand and Kerry Emanuel, the MIT climate scientist who confirmed the increase in North Atlantic storms over the 20th century, attributed that increase to local climate effects. This could be changes in atmospheric patterns and ocean currents or even the reduction of aerosols in the atmosphere during the latter half of the 20th century.

However, even with the recent increase in storm frequency in the North Atlantic, Chand says that even that region of the ocean is still seeing fewer tropical storms and hurricanes than there were in pre-industrial times.

Watch below: NASA scientist explains the 2020 record hurricane season's place in the climate record

No reason for celebration

"It may initially seem like good news fewer cyclones are forming now compared to the second half of the 19th century," Chand wrote. "But it should be noted frequency is only one aspect of risk associated with tropical cyclones."

Climate change is shifting where tropical cyclones form, pushing them towards regions which do not have the infrastructure to handle their impacts. Storms are also growing stronger as sea surface temperatures increase, and we are seeing them stalling in place for extended periods of time. Research also shows that cyclones are maintaining their strength for longer after they make landfall, thus drawing out the impacts of their powerful winds, torrential rainfall, and storm surge.

As a result, despite fewer tropical cyclones, the risks of devastating damage to coastal regions from these storms are rising.

(Thumbnail image of Pacific hurricane Linda, from 2021, courtesy NASA Worldview)