Climate change has altered where tropical cyclones occur, study says

Researchers confirm that the increasing frequency of hurricanes in the North Atlantic cannot be explained by natural climate processes only.

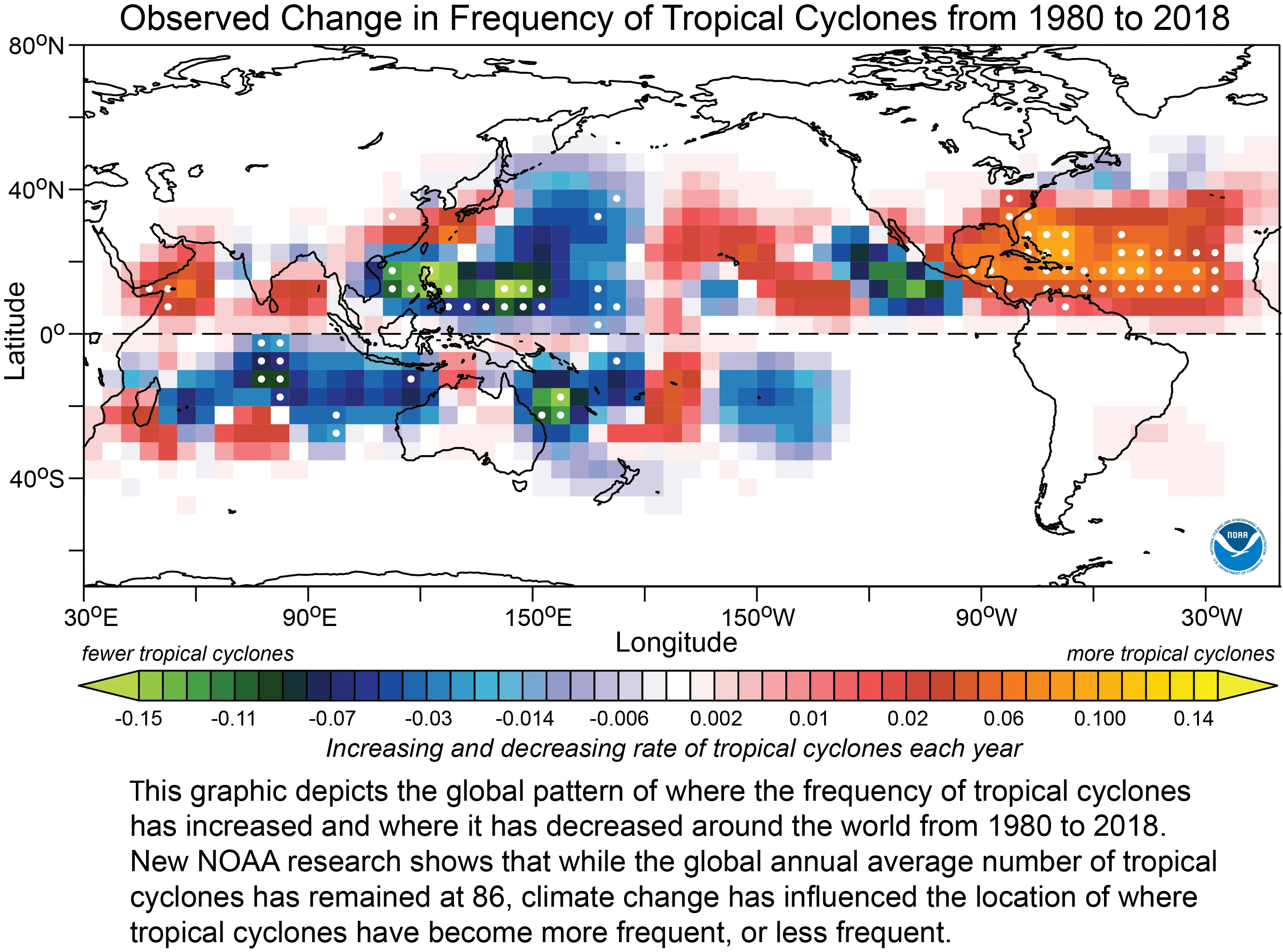

The number of tropical cyclones in the North Atlantic and Central Pacific has been on the rise since 1980 and a study says that this increase has likely been caused by human-released greenhouse gas emissions, aerosols and volcanic eruptions.

Other parts of the world, including the western Pacific and in the South Indian Ocean, have seen a decline in tropical cyclones. Knowledge of how tropical cyclones are impacted by climate change is limited and has considerable uncertainty due to a lack of reliable historic data before 1980. Despite this, the researchers conclude that the increase of tropical cyclones in certain regions cannot be explained by natural climate processes only.

A tropical cyclone is a rotating, organized system of clouds and thunderstorms that originates over tropical or subtropical waters and has closed, low-level circulation, as defined by NOAA. Tropical cyclones that occur in the North Atlantic, central North Pacific, and eastern North Pacific with a maximum sustained winds of 119 km/h or higher are hurricanes, whereas those that occur in the Northwest Pacific are called typhoons.

Though the number of tropical cyclones that occur each year has not changed, the relatively rapid shift in frequency in certain areas is a pattern that is being observed “for the first time,” according to Hiroyuki Murakami, a climate researcher at NOAA’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory and lead author of the study.

Credit: NOAA

Just a few weeks after this study was published, experts at Colorado State University (CSU) released their forecast for the Atlantic hurricane season this year and expect hurricane activity to be above average this year. The researchers cite the absence of an El Niño as the primary factor for this forecast and also state that the unusually warm tropical and subtropical Atlantic sea surface temperatures could favour an active 2020 Atlantic hurricane season.

CSU states that the probability of a major hurricane making landfall in the U.S. is 69 per cent, which is above average for the last century when the likelihood was only 52 per cent. The Caribbean is seeing a 58 per cent likelihood of a major hurricane making landfall, which is worrisome for countries that are still recovering from Hurricane Dorian (2019) that caused hundreds of fatalities and billions of dollars in damages.

CLIMATE CHANGE AND HURRICANES

The rate of evaporation speeds up as the planet warms, which causes a greater amount of water vapour to be stored in the atmosphere. A 1°C increase in global temperatures causes the atmosphere to hold seven per cent more moisture, which creates more water vapour in the air that can act as a ‘fuel’ for hurricanes. Water vapour releases latent heat that warms the surrounding air as it changes from liquid to vapour. As a hurricane forms, it draws surface air towards its center where winds strengthen and cause even more evaporation.

The regions that are seeing an increase in tropical cyclone frequency are also seeing single cyclone events that have a high likelihood of being made more severe by climate change. NOAA says that a 2°C increase in global temperatures will likely cause 10-15 per cent more rainfall within 100 km of a tropical cyclone and they will likely be between 1 and 10 per cent more intense. More tropical cyclones could reach Category 4 and 5 levels because of warmer temperatures, which would cause more severe damages and higher fatalities.

Hurricane Dorian destruction in Bahamas on September 2, 2019. Credit: Wikimedia Commons/United States Coast Guard

Increasingly severe hurricanes in the Atlantic Basin could cast a dire outlook on many communities that have yet to recover from previous hurricanes, such as Katrina (2005) and previously mentioned Dorian (2019). The study notes that the climate models indicate a decrease in tropical cyclones by 2100 when the annual global average could drop from 86 to 69. However, researchers emphasize that even though there might be fewer tropical cyclones, it only takes one to remind us of their tolls.

“We hope this research provides information to help decision-makers understand the forces driving tropical cyclone patterns and make plans accordingly to protect lives and infrastructure,” Murakami says.