Climate impacts are worsening faster than they ever have on record

Melting glaciers, rising sea levels, and record heat are all intensifying according to an early-edition WMO report aimed at the COP27 negotiations.

A new report has revealed that, over the past eight years, the impacts of climate change are not only growing worse, the rate at which they are getting worse is accelerating.

The World Meteorological Organization released their provisional State of the Climate Report for 2022 this week. These annual reports closely examine the levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, as well as key impacts of climate change — global temperature rise, sea ice and glacier loss, sea level rise, ocean heat, and extreme weather — to put them into context with the rest of our climate record. Although this year is not yet over, the WMO produced this early edition to emphasize to the negotiators at the COP27 climate conference the urgency of our situation.

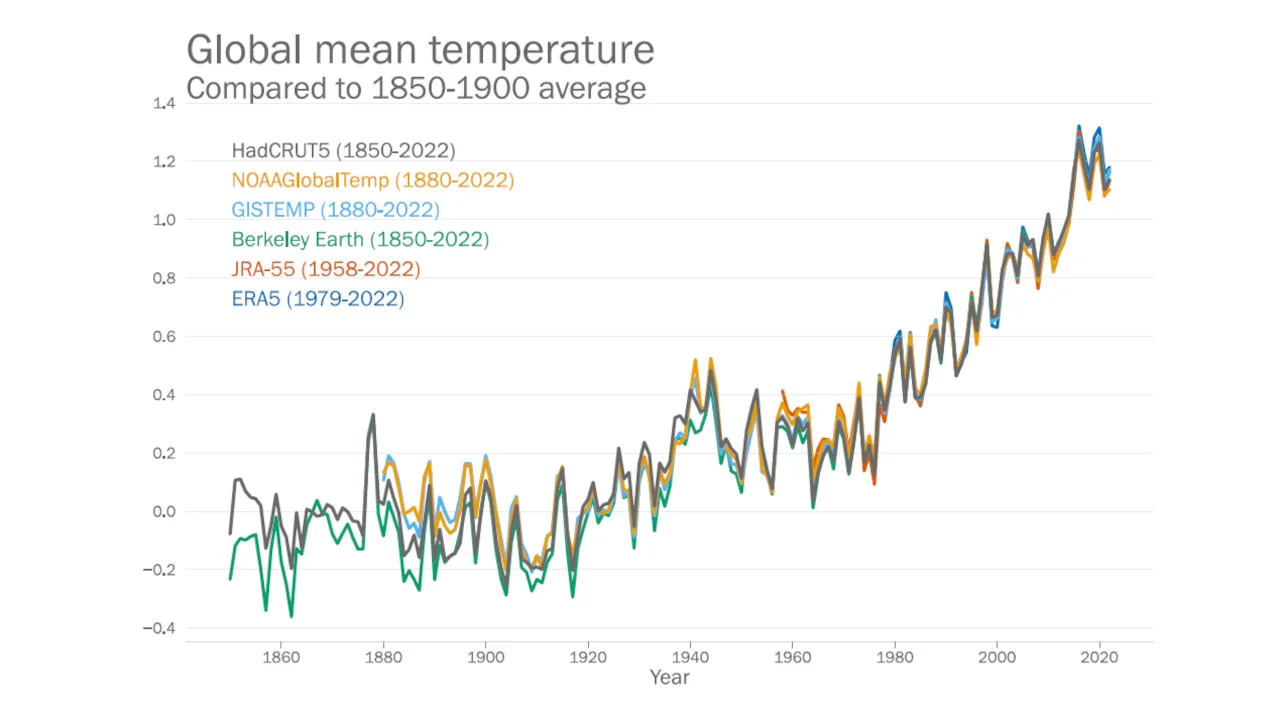

So far, 2022 is on track to become the sixth warmest year of the past 143 years. Additionally, the stretch from 2015-2022 is looking to clock in as the eight warmest years of that entire period.

This graph shows the rise in global temperature (°C) compared to pre-industrial conditions (1850–1900), year-by-year since 1850, using six data sets. 2022’s temperature is based only on the average from January to September. (WMO)

What’s especially alarming is that the past two years have ranked so high. Since 2020, a persistent La Niña pattern across the Pacific Ocean has kept the global average temperature slightly cooler than the current normal. Without that La Niña, 2021 and 2022 may have challenged 2016 for its spot as hottest year on record. If there had instead been an El Niño over the past two years, it would have likely guaranteed that record.

“We have such high levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere now that the lower 1.5°C of the Paris Agreement is barely within reach,” WMO Secretary-General Prof Petteri Taalas said in a press release.

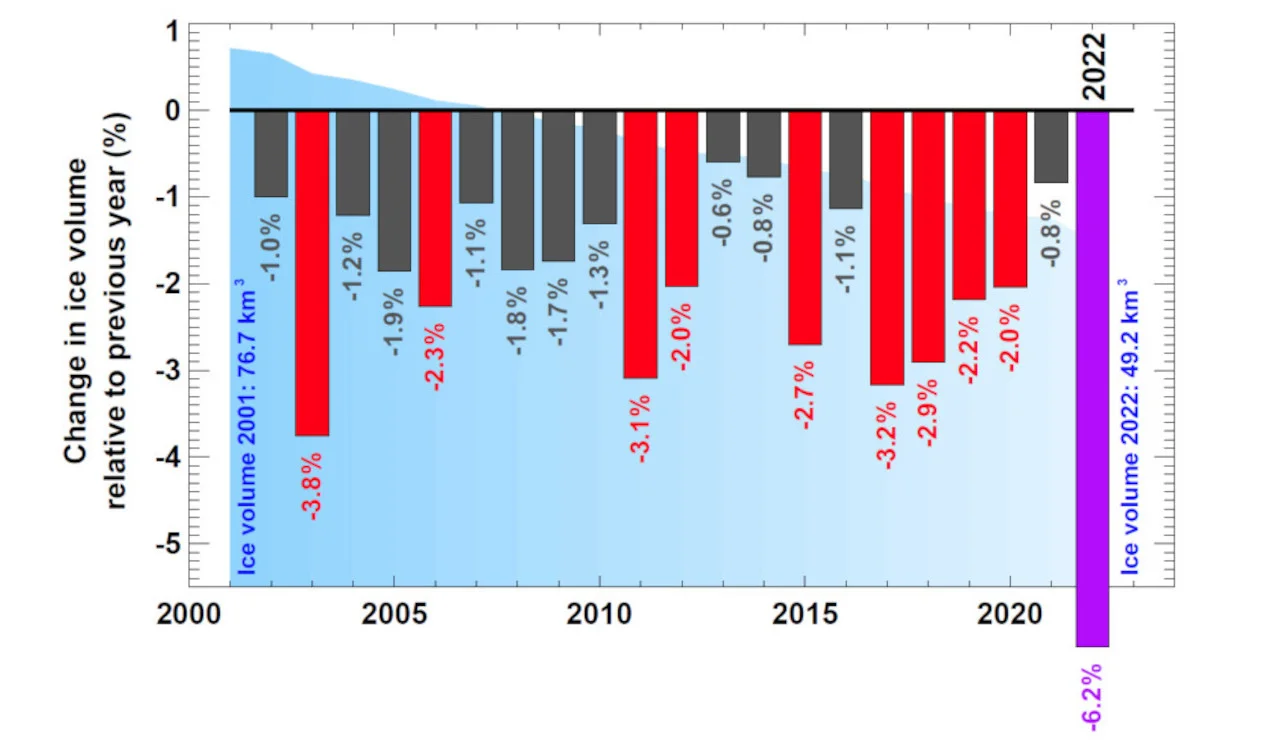

According to the report, glaciers in the European Alps have suffered record-shattering melting so far this year, with average losses measuring between three and four metres throughout.

WATCH ALSO: 4-year timelapse shows Alps glacier melt away in seconds

Switzerland alone saw its biggest drop in ice volume so far, and has lost over one-third of its glacial ice between 2001 and 2022.

“It’s already too late for many glaciers and the melting will continue for hundreds if not thousands of years, with major implications for water security,” Taalas said.

Total annual loss of Swiss glaciers related to the current ice volume 2002-2022. The vertical bars indicate the percentage change in ice volume relative to the previous year. Red bars are the 10 largest relative mass losses on record. The purple bar is the relative mass loss for 2022. The blue shaded area in the background represents the overall ice volume. (WMO)

For sea ice, the Arctic saw a below average minimum extent in September, continuing the long-term decline there. In Antarctica, which has seen increasing sea ice extent over the past few decades, the February 2022 summer minimum was the lowest seen on record.

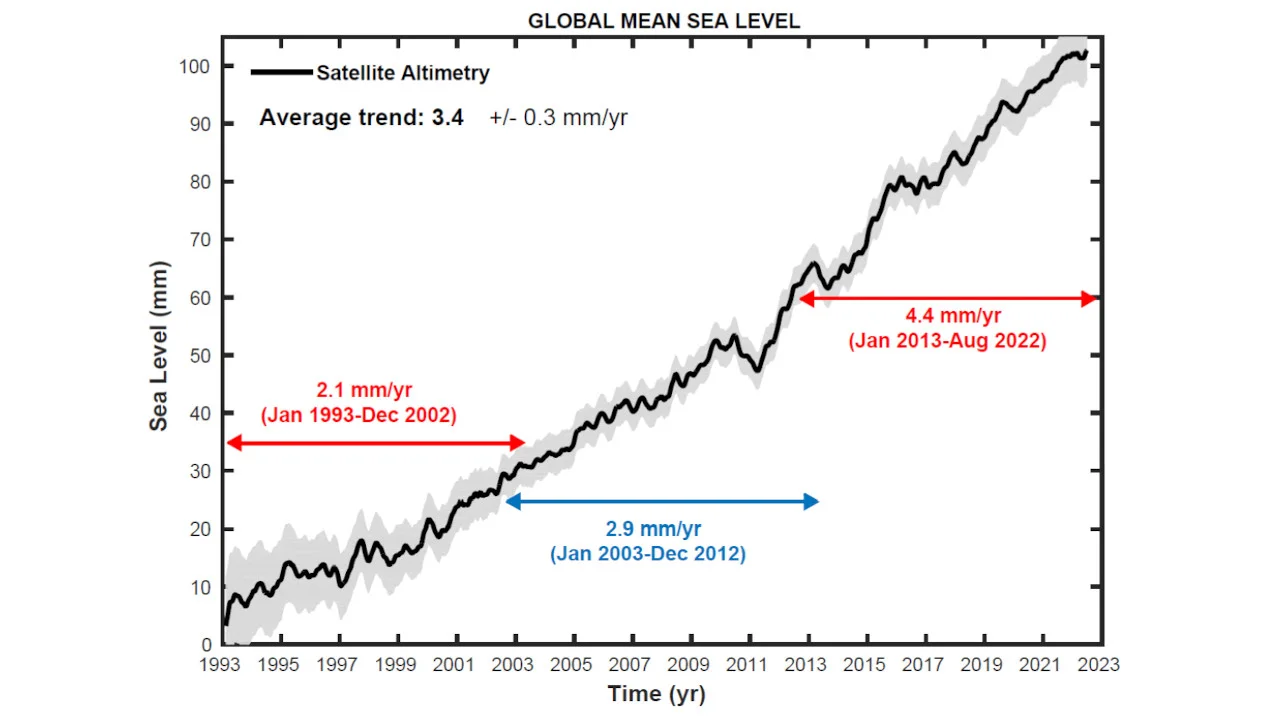

Meanwhile, sea levels continue to rise, and are now an average of at least 100 millimetres higher than they were in the early 1990s. Also, the rate that the ocean surface is rising is accelerating. The rate over the past 10 years has more than doubled from what it was 30 years ago, and roughly 10 per cent of the total rise was seen in just the past two-and-a-half years.

Partly, this rise is due to runoff from melting glaciers. However, thermal expansion is also playing a major role, with the volume of the oceans literally growing because of the increase in water temperature. According to the report, over half of the ocean area on Earth experienced at least one marine heatwave this year. In contrast, only a little over one-fifth of the ocean surface has had a marine cold spell in 2022.

“The rate of sea level rise has doubled in the past 30 years,” Taalas said. “Although we still measure this in terms of millimetres per year, it adds up to half to one metre per century and that is a long-term and major threat to many millions of coastal dwellers and low-lying states.”

Global mean sea level evolution from January 1993 to August 2022 (black curve) with associated uncertainty (shaded area). Decadal trends are shown as well, with an average rise of 2.1 mm/yr between 1993 and 2002, 2.9 mm/yr from 2003-2012, and 4.4 mm/yr from 2013 to the present. (WMO)

Climate is the accumulated record of weather conditions, and one key indicator that our climate is changing is extreme weather that pushes beyond the boundaries of what has come before.

Several instances of extreme weather are also noted in the report.

Record-breaking heat waves were felt across Europe, with the UK experiencing its first temperature above 40°C on record. The hot, dry weather also caused the Rhine, Loire, and Danube rivers to fall to critically low levels.

China suffered its most extensive and longest heatwave on record.

India and Pakistan suffered through record heat in April and May, followed up by record rainfall in July and August that caused devastating floods in Pakistan.

Flooding also impacted Madagascar due to a series of cyclones that made landfall across southern Africa in January and February.

Meanwhile, in East Africa — Kenya, Somalia, and southern Ethiopia — drought conditions have been intensifying, as the region has been suffering the longest stretch of dry conditions in the past 40 years. According to the WMO, an estimated 18-19 million people have faced “crisis” levels of food insecurity up until June of 2022, and this will only get worse if crops fail due to another dry season.

“All too often, those least responsible for climate change suffer most – as we have seen with the terrible flooding in Pakistan and deadly, long-running drought in the Horn of Africa. But even well-prepared societies this year have been ravaged by extremes — as seen by the protracted heatwaves and drought in large parts of Europe and southern China,” said Taalas. “Increasingly extreme weather makes it more important than ever to ensure that everyone on Earth has access to life-saving early warnings.”

As the discussions at COP27 have demonstrated, the lives at stake depend on how quickly governments and industries respond to these increasingly severe warnings.