Blocking the Sun’s rays too risky to consider as climate change solution

An open letter to the world's governments says that we should not consider solar geoengineering as a viable solution to climate change.

Scientists from around the world are calling for global leaders to ban the development of technologies that would cool Earth's climate by dimming the Sun's rays. Such programs, they say, are far too risky and may actually do more harm than good.

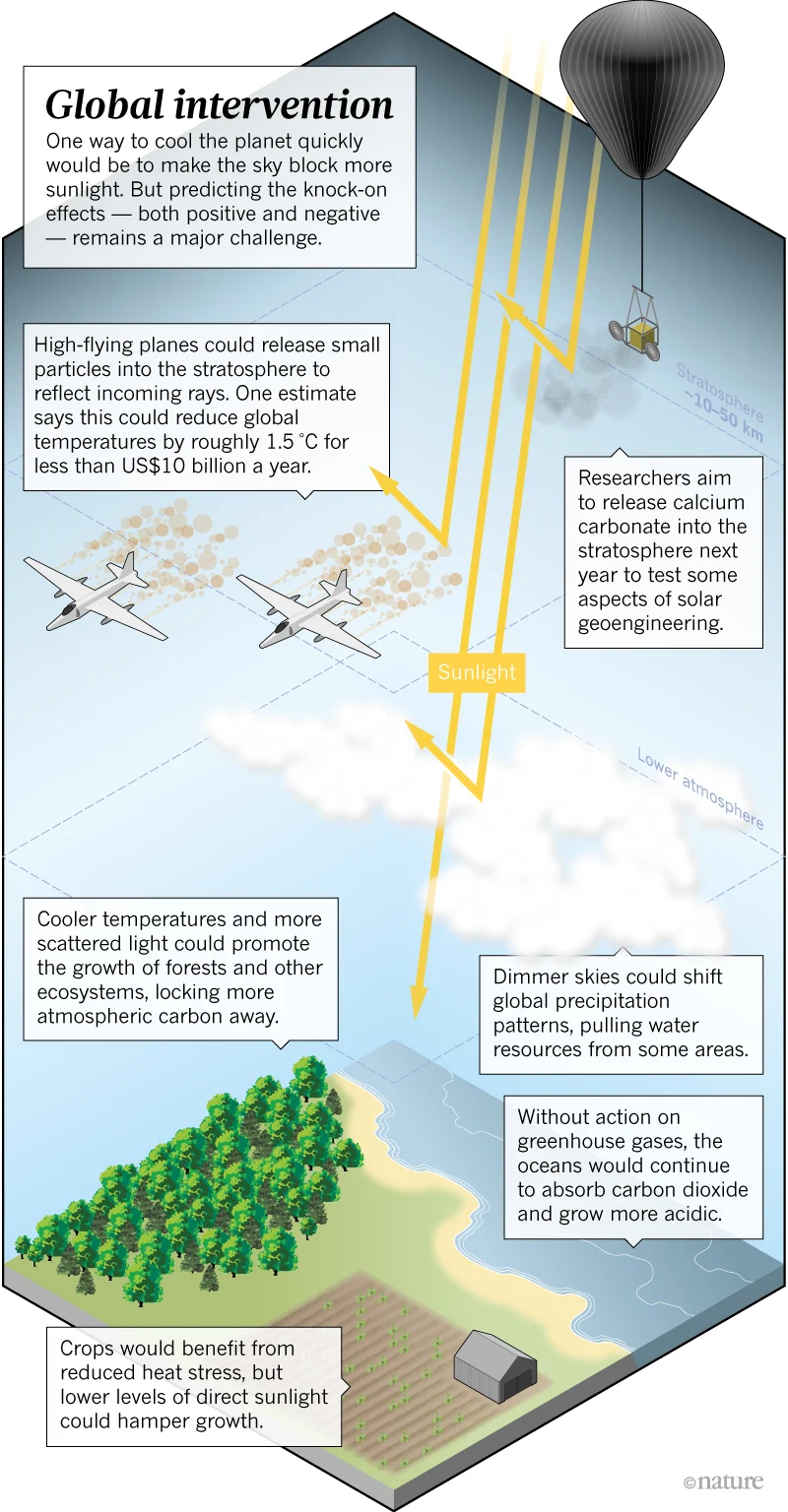

Solar geoengineering is an idea proposed some years ago, which would see the use of technologies to block some of the Sun's light from reaching Earth's surface. Some of the more achievable plans for how to go about this have ranged from having aircraft spread reflective particles across the stratosphere, to the use of ships to convert surface seawater into bright clouds that reflect more sunlight, to altering the properties of high-altitude cirrus clouds to allow more heat to escape into space. The purpose behind all of these ideas is to lessen the impacts of global warming and climate change, while we ramp up efforts to reduce greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere.

Solar geoengineering has both potential benefits and potential negative consequences. Credit: Nature

The concepts behind the global use of such technologies are still hypothetical. There are no global-scale solar geoengineering projects currently in operation, nor are there any currently in development.

Despite this, a group of over 70 scientists from around the world have signed an open letter to the United Nations and the governments of the world, calling for an international ban on the development and use of global-scale solar geoengineering technologies.

In their letter, they list three reasons for this call: the poorly-understood risks and uncertain impacts of implementing such a system, the distraction these ideas represent from efforts to mitigate climate change through decarbonizing our society, and the inability of current world governments to fairly implement and maintain such long-term plans.

"The risks of solar geoengineering are poorly understood and can never be fully known," Professor Frank Biermann, the leader of the call for the Non-Use Agreement on Solar Geoengineering, said in an Utrecht University press release. "Research on solar geoengineering is not the preparation of a Plan B to prevent climate disaster, as its advocates argue. It will instead simply delay and derail current global climate policies. Moreover, the current system of international institutions is incapable of effectively regulating the deployment of this technology on a global scale. Solar geoengineering is no solution."

If signed, the International Non-Use Agreement on Solar Geoengineering would represent a nation's commitment to:

not spend national funds on the development of solar geoengineering technologies

ban outdoor testing of these technologies within that country's jurisdiction

restrict the granting of patents for solar geoengineering technologies

ban deployment of these technologies, even if developed by a third party

oppose solar geoengineering as a policy option for international institutions, including assessments by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

This infographic outlines the commitments and measures of this International Solar Geoengineering Non-use Agreement. Credit: Biermann et al., WIRES Climate Change

While this call is certainly motivated by caution and the acknowledgment of society's limitations, it is not without its critics.

Holly Buck is a researcher from the University at Buffalo who has authored several papers and a book about solar geoengineering and its consequences. In an opinion piece on the MIT Technology Review, Buck agreed with several of the points presented in the letter. At the same time, though, she expressed concern over the exact wording of this Non-Use Agreement.

"The trouble with [the] proposal is that it fails to adequately distinguish research from development or deployment," Buck wrote. "It's a thinly veiled (or maybe not at all veiled) attempt to stifle research on the topic."

As she pointed out, if signing nations must oppose assessments by the IPCC, "we would not be able to know how the foremost body of international scientists appraises the science."

Expanding on her thoughts on Twitter, Buck pointed out that restricting public research on solar geoengineering would prevent us from knowing if there are potential benefits, but it would also leave the research to private organizations and the military — both of whom may not report negative consequences. The alternative she proposed was for "a publicly funded research program that can be designed to look systematically at all risks, integrate social science, produce open data, and encourage international cooperation."

The Sun's rays shine down onto Earth in this photo snapped on July 4, 2018, by a camera mounted on the outside of the International Space Station. Credit: NASA

Last year, the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine proposed spending at least $100-200 million on researching the topic over the span of five years.

As their report states: "The centerpiece of this portfolio should be reducing GHG emissions, removing and reliably sequestering carbon from the atmosphere, and pursuing adaptation to climate change impacts that have already occurred or will occur in the future. Concerns that these three options together are not being pursued at the level or pace needed to avoid the worst consequences of climate change — or that even if vigorously pursued will not be sufficient to avoid the worst consequences — have led some to suggest the value of exploring additional response strategies. This includes solar geoengineering."

The plan for this study is not just to examine the feasibility of solar geoengineering. It would also thoroughly explore the risks of harmful unintended consequences, and it would approach the subject of how the technology could be deployed ethically. Additionally, since it only represents a tiny fraction of the total budget to address climate change it is not expected to distract from other solutions, and based on all the potential risks and consequences it would address the subject of whether we should be pursuing this technology at all.

"The US solar geoengineering research program should be all about helping society make more informed decisions," Chris Field of Stanford University, who led the committee that wrote the report, told The Guardian at the time. "Based on all of the evidence from social science, natural science, and technology, this research program could either indicate that solar geoengineering should not be considered further, or conclude that it warrants additional effort."

An editorial published in Nature, in May of 2021, summed up the issues with banning research well: "solar-geoengineering research brings risks, and there are other, more-promising ways to address global warming. But the world remains on a path to dangerous climate change, and future generations will bear an increasing burden. Governments need to step up climate efforts, and evaluate all possible options for action. If solar geoengineering is harmful, leaders will need evidence so that they can rule out the technology."