Antarctica's Doomsday Glacier 'really holding on today by its fingernails'

Thwaites Glacier has seen periods of very rapid retreat over the past 200 years.

New hi-res scans of the seafloor at the base of Antarctica's Thwaites Glacier have revealed just how quickly the glacier has retreated in the past. The data are raising new alarms about how much faster the Doomsday Glacier's retreat may become in the years ahead.

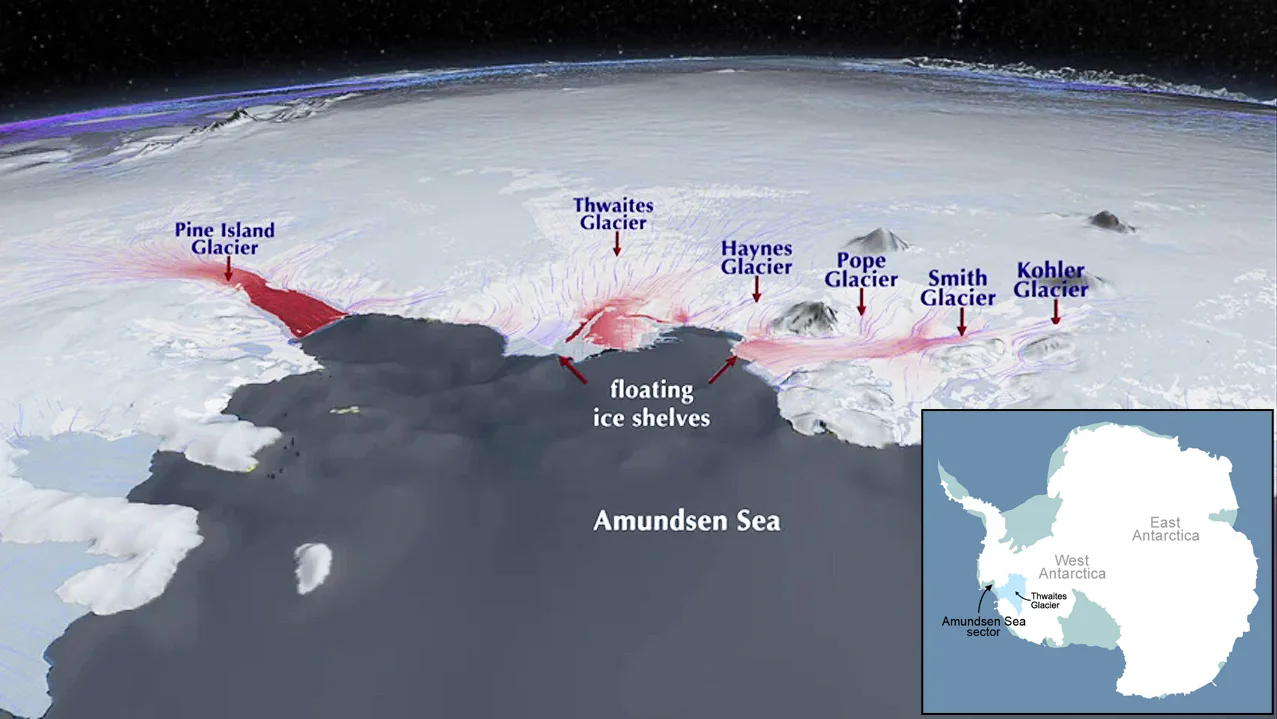

The West Antarctic Ice Sheet is one of the most important locations in the world when it comes to the impacts of climate change. This immense ice sheet is losing ice at an accelerating rate, in part due to the retreat of the glaciers that are "pinning" it in place.

The widest of these is Thwaites Glacier, located on the coast of the Amundsen Sea.

These maps show the location of Thwaites Glacier, pinned between the West Antarctic Ice Sheet and the Amundsen Sea. (NASA)

Satellite data has shown that, over roughly the past decade, Thwaites has been retreating at a rate of about one kilometre every year. This, alone, has caused concerns in the scientific community. Without a sizable ice shelf to push back against the glacier's flow, Thwaites is in danger of collapsing due to the impacts of climate change. If that were to happen, the ice released would not only immediately contribute to sea level rise, it would also open up a wide path for the core of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet to begin flowing down to the ocean.

The dire consequences of Thwaites' eventual collapse has earned it the nickname the "Doomsday Glacier."

READ MORE: Antarctica is crumbling at its edges, says NASA scientist

In 2019, a lack of sea ice in the Amundsen Sea gave researchers unprecedented access to the leading edge of the Thwaites ice shelf — the small portion of the glacier that currently floats out over the water. Taking advantage of this opportunity, a team of scientists made the journey along with a tiny orange submersible, named Rán, which they used to produce a high resolution map of the seafloor in front of the glacier.

The purpose of this was to get an idea of how quickly Thwaites has retreated in the past, which would then improve our understanding of how fast it may retreat in the future.

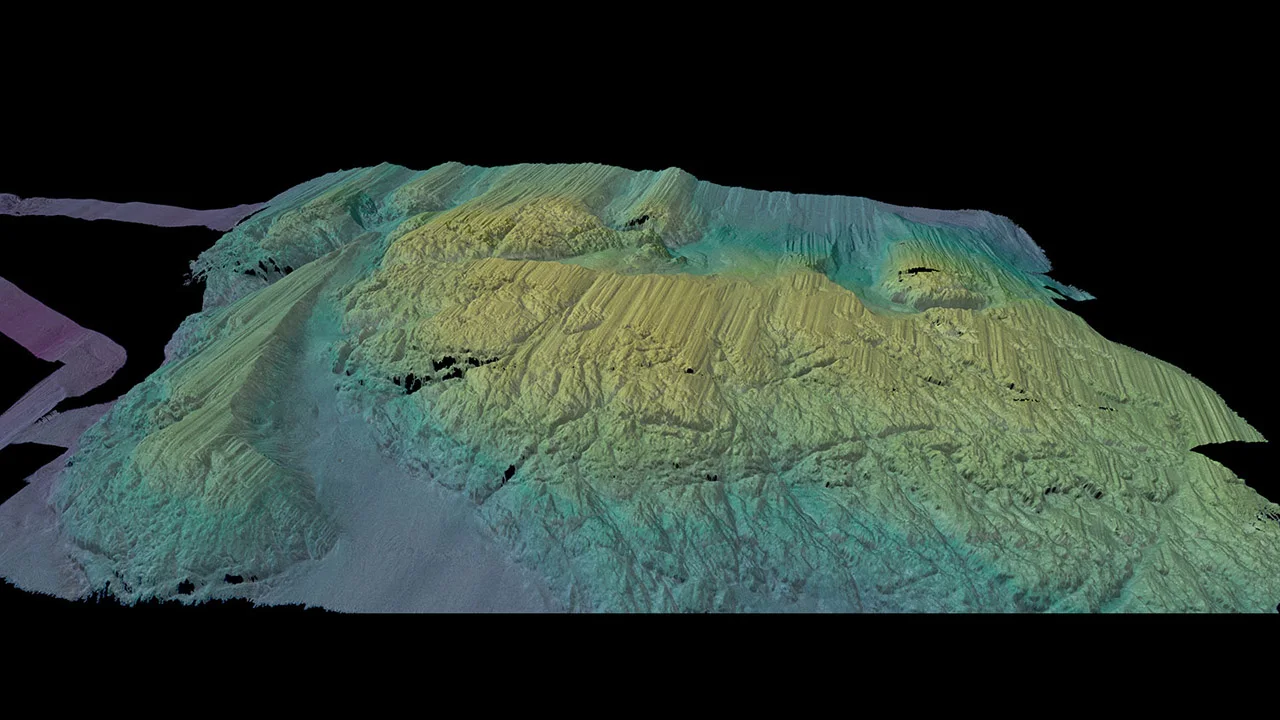

A 3D-rendered view of the seafloor shape, coloured by depth, collected by Rán across a seabed ridge, just in front of Thwaites Ice Shelf. The grooves in the seabed were carved by the retreat of the glacier's leading edge, as it rose and fell with the local daily tides. (Alastair Graham/University of South Florida)

The resulting map revealed grooves carved into the seabed by the retreat of the glacier's grounding line — the point where the ice makes contact with the seafloor. The map was so detailed that they were also able to pick out the saw-tooth pattern along the peaks of these grooves, which was produced as the grounding line was lifted off the seafloor during high tide and settled back down during low tide.

"The images Rán collected give us vital insights into the processes happening at the critical junction between the glacier and the ocean today," Anna Wåhlin, the physical oceanographer from the University of Gothenburg who operated Rán at Thwaites, said in a press release.

The researchers' analysis of the map showed that Thwaites experienced periods of very rapid retreat within the past 200 years.

"Our results suggest that pulses of very rapid retreat have occurred at Thwaites Glacier in the last two centuries, and possibly as recently as the mid-20th Century," Alastair Graham, the University of South Florida marine geophysicist who led the study, explained in the statement.

At one point, the study notes, over the span of five and a half months, the glacier's grounding line detached from the seabed and retreated at over twice the rate seen more recently through satellite observations.

Rán, a Kongsberg HUGIN autonomous underwater vehicle, amongst sea ice in front of Thwaites Glacier, after a 20-hour mission mapping the seafloor. (Anna Wåhlin/University of Gothenburg).

This discovery of these rapid retreat pulses is renewing concerns about the "doomsday" potential of Thwaites.

"Similar rapid retreat pulses are likely to occur in the near future when the grounding zone migrates back off stabilizing high points on the sea floor," the study said.

"Thwaites is really holding on today by its fingernails, and we should expect to see big changes over small timescales in the future — even from one year to the next — once the glacier retreats beyond a shallow ridge in its bed," said study co-author Robert Larter from the British Antarctic Survey.

(Thumbnail image courtesy NASA/OIB/Jeremy Harbeck)