Indigenous constellations; part-science, part-art, all-important

We're accustomed to the Greek and Roman constellations, but Canada's Indigenous Peoples have a rich history of sky stories, and we can all learn a lot from them.

Have you ever checked your horoscope to see what the day has in store for you? Whether you’re a dramatic Leo, a scientific Aquarius, or an adventurous Sagittarius, you’re looking to the ancient Greeks and Romans to tell your story. You don’t have to look that far.

The Indigenous Peoples of Canada have been connecting with the world around them via sky stories for epochs. Though the stories have been disrupted, there are leaders within the Indigenous community that continue to teach the importance of connecting with their stories as a way to connect with ourselves, others and nature.

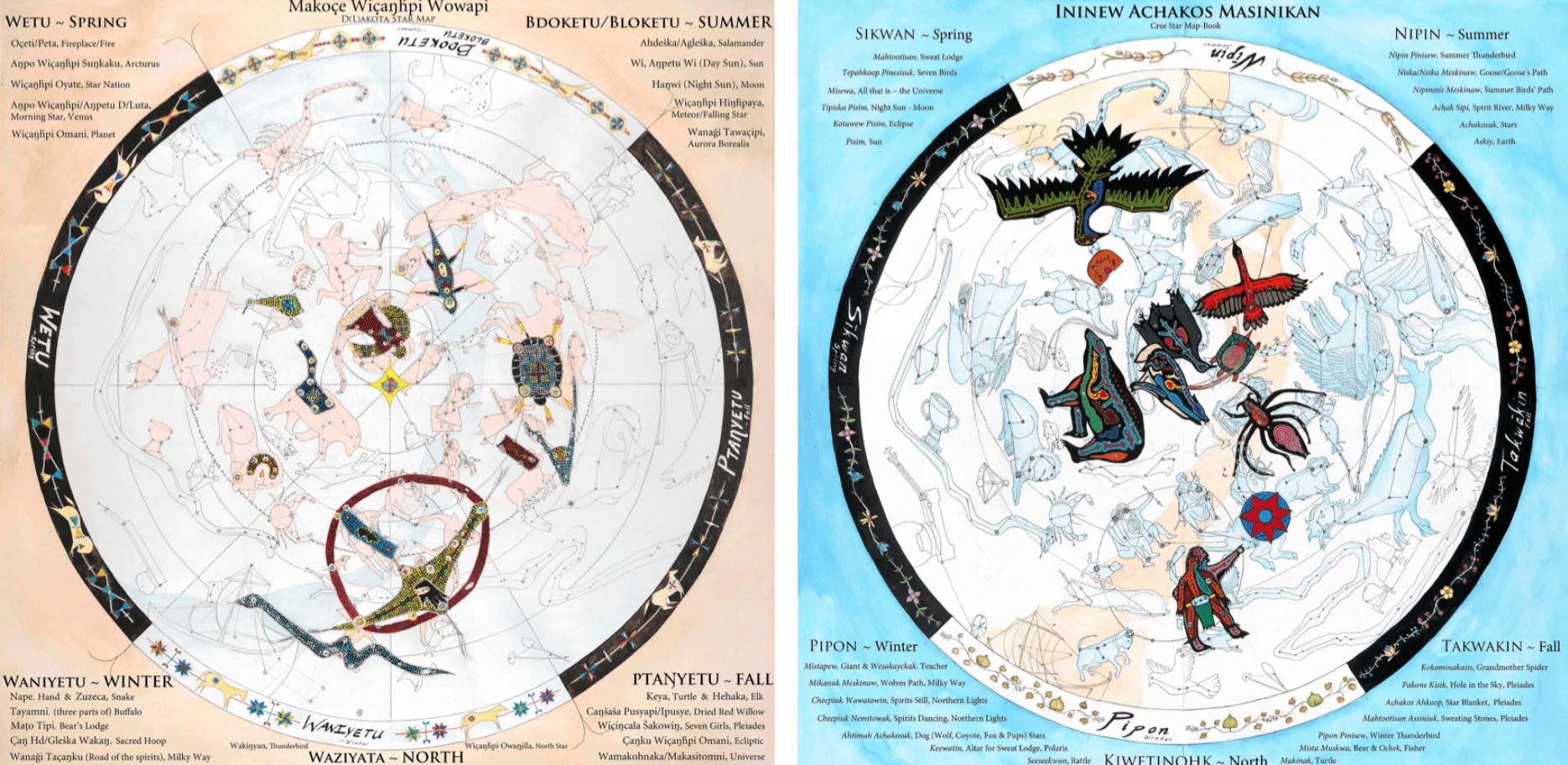

And the stories are darn-right beautiful, in their meanings and visually. Before we get into some of the science, meanings and expert insight, take a look at these two beautiful interpretations of what hangs out in our skies.

Star maps from Dakota/Lakota and Ininew/Cree First Nations. Credit: Annette S. Lee, William P. Wilson, Carl Gawboy, © 2012, Annette S. Lee & Jim Rock © 2012, and Annette Lee, William Wilson

SEE ALSO: Mi'kmaq artist captures life — and the changing coastlines — on P.E.I.

THE SCIENCE OF INDIGENOUS CONSTELLATIONS

Astronomy is the oldest form of science. It helps us understand how to prolong survival and how to navigate the world while we’re here. Astronomy is critical in understanding the weather, water, and climate changes. It’s a pretty big deal. And it’s pretty significant that it’s culturally normalized to only talk about one interpretation of sky stories.

Will Morin, a professor in the Department of Indigeous Studies at the University of Sudbury, explains that many Indigenous communities use stories of the stars to communicate seasonal focuses and traditions. And living in what is now Canada, we can all appreciate the very distinct four seasons. These are some key events that Indigenous Peoples use to connect the sky, the season, the people and the environment around them:

Winter: a time for family, storytelling, and reconnection with one another

Spring: the time when ice melts, floods could occur, and therefore danger is imminent

Summer: a time for trapping and enjoying hanging out in the warm weather

Fall: the season to hunt moose and get ready for the winter

So for example, what is widely known as Pegasus, the Anishinaabe people know as the Moose. And it couldn’t get more Canadian even if we had a maple syrup-dipped Celine Dion constellation.

Credit: Ontario Parks Blog

Morin continues to associate the connection between Indigenous star stories and science by explaining the pattern of a dreamcatcher (another nice intersection between art and science). Morin explains that the “Dreamcatcher is more than a “craft”, it is in fact part of the creation stories for some tribes. The dreamcatcher pattern echoes the math formula for ‘phi’ found in nature. This pattern is a star map of the constellations.”

The Indigenous studies professor continues to connect the sky stories with earth sciences by explaining that “Looking to the stars helps us to prepare for the future and links us to the past. The animals and beings among the constellations related to our relationship here on the earth, with the animals, the plants, and each other.”

If these stories have had great impacts on generations of Indigenous Peoples of Canada, then why won’t we hear about them? Why aren’t we still learning from them? How can we reconnect with the history of the people and land of Canada?

THE RECLAIMED ART OF INDIGENOUS SKY STORIES

J'net Ayayqwayaksheelth, the Indigenous Outreach and Learning Coordinator for the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM), explains that there’s a vast diversity of Indigenous star stories that span our country. But the Potlatch Ban, that span from 1884-1951, disrupted the transmission of traditions, including singing, dancing, seasonal celebrations and storytelling.

Ayayqwayaksheelth shares that in times when we need to ground ourselves, like during a worldwide pandemic, star stories provide a sense of belonging by learning directly from our ancestral homelands. She continues to explain that stories offer “Timeless knowledge of being in good relations with ourselves, our kin, and the land.’

Morin echos Ayayqwayaksheelth’s sentiments by sharing that “constellation beings tell us of when to hunt, to plant, to rest, when to sacrifice and prepare for the changes to come.” Though many Canadians don’t connect with hunting, or even planting, we’re a country of diversity, and learning about new ways to rest and prepare for changes can provide additional strength throughout the everchanging seasons.

Luckily, there are experts like J'net Ayayqwayaksheelth and Will Morin to help spread the word.

RESOURCES TO LEARN ABOUT INDIGENOUS SKY STORIES

There are certainly many ways to learn and experience the arts and sciences that comprise Indigenous sky stories. Ayayqwayaksheelth, and the ROM Learning Department, directed us to the knowledgeable and engaging Wilfred Buck. Buck has live virtual events, but his stories are also accessible on YouTube.

There are also books that share the sky stories of a particular Indigenous group. For example, this Ojibwe Sky Star Map.

Overall, Canada is lucky to be composed of rich cultural and biological diversity. Indigenous star stories teach us about Canada's heritage and suggest ways to connnect with our environment to move into a stronger future.