2020 is on track to be Earth’s warmest year on record

Despite the widespread drop in greenhouse gas emissions during the COVID-19 pandemic, NOAA reports that global temperatures will be record-breaking in 2020.

While the COVID-19 lockdowns have caused dramatic declines in greenhouse gas emissions, abnormally warm global temperatures are telling us that the climate is still heading into unprecedented territory.

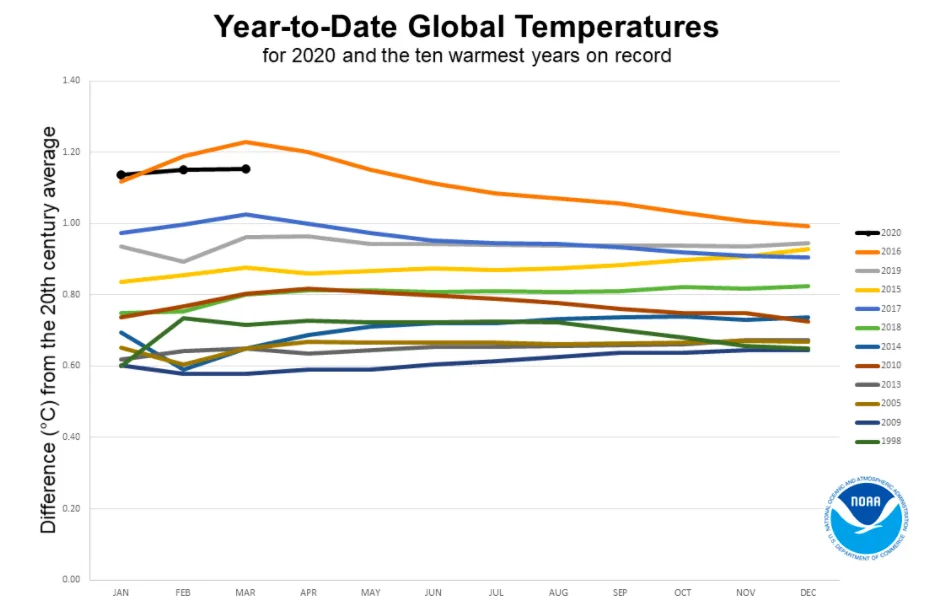

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has reported that there is a 75 per cent chance 2020 will be the warmest year on Earth since record-keeping began in 1880. Global temperatures are expected to be warmer than those in 2016, which was declared the warmest year on record at the time. The unusually strong El Niño event of 2015-2016 contributed to 2016’s record-breaking warmth. There are currently no indications that we will see an El Niño event this year, however, which makes NOAA’s projections particularly concerning.

Even if 2020’s temperatures fall short of those recorded in 2016, NOAA says that this year is 99.9 per cent likely to be in the top five warmest years on record. These projections were announced by Derek Arndt, the head of climate monitoring at NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information, during a news conference call in mid-April.

NOAA made these projections by analyzing monthly temperatures from the past 40 years and generated 10,000 potential outcomes for how the overall global temperature pattern could trend. The scientists calculated the 75 per cent likelihood based on the abnormally high temperatures that were recorded this past January, February and March, which indicate a global trend that will be warmer than 2016.

Credit: NOAA

The graph above is NOAA's 'horserace' visualization of temperature anomalies for 2020, which shows the difference in degrees Celsius between the observed temperatures and the 20th century average temperature. Each line represents a cumulative value for the year. For example, the January value is that month’s global temperature anomaly, the February value is the average of the January and February global temperature anomalies, and the March value will be the average of the January, February and March global temperature anomalies, and so on.

January was a stand-out month during this past winter season, as it was the warmest on record and the 44th consecutive January that was above the 20th-century average. During this time, Europe experienced an average temperature anomaly of 3.1°C and a large region of the continent stretching from Norway to western Russia saw average monthly temperatures 6°C above normal values.

COULD COVID-19 CHANGE THIS?

The widespread lockdowns that have been implemented to slow the spread of COVID-19 have slashed greenhouse gas emissions in some of the most polluted parts of the world. Satellites from the European Space Agency found that levels of nitrogen dioxide over cities and industrial areas in Asia and Europe were lower than in the same period in 2019, with some areas seeing up to a 40 per cent decline. Canadians have also seen improvements in air quality, with many residents in Vancouver remarking at the stunning scenes in the Fraser Valley.

While the pandemic is showing us that emissions can be lowered, the science shows that if the entire world stopped emitting carbon dioxide emissions tomorrow, the climate will still warm for decades. This is due to the delay between greenhouse gas emissions and the warming response of the atmosphere, which can be decades or centuries later, and the significant amounts of greenhouse gases that have already been released.

Once greenhouse gases are emitted into the atmosphere, they accumulate and trap heat near the surface of the Earth, which is then distributed across land and oceans. Between 65 to 80 per cent of the carbon dioxide that is released into the atmosphere will dissolve into the oceans, which can take anywhere from a few decades up to 200 years. The remaining 20 to 35 per cent of the human-released carbon dioxide takes centuries to thousands of years to break down through other processes, such as rock formation.

The climate change impacts we are currently observing, such as the abnormally warm winter we just experienced, are a result of the amount of carbon dioxide previously released into the atmosphere. Slowing the amount of carbon that we release will help reduce the severity of future climate change, but it is not a solution for the present situation.

Preventing the accumulation of heat in our atmosphere would involve unprecedented actions to eliminate all greenhouse gases, reverse deforestation and other land-use that is responsible for carbon release, and radically change our agricultural industries, among other necessary steps. Despite the disconcerting projections, scientists say that climate change can be managed if greenhouse gas emissions are lowered to levels that will have slower impacts, which will give us the chance to adapt to the new conditions and successfully manage the hazards we may face.