Melt or move? See what'll happen to that PEI-sized iceberg

Meteorologist/Science Writer

Monday, July 17, 2017, 6:36 PM - Iceberg A-68 broke off from Antarctica's Larsen C ice shelf a week ago, becoming one of the largest iceberg seen during the satellite era, but now what? What will be the ultimate fate of this immense chunk of ice?

The Larsen C ice shelf is a thick sheet of ice that floats atop the frigid waters along the east coast of the Antarctic Peninsula. Since at least 2010, scientists had been monitoring a sizable crack that had formed near the leading edge of the ice shelf, and watched over the past several months as the growth of this crack accelerated until it finally broke off a sizable chunk, in the form of Iceberg A-68, sometime between July 10 and 12, 2017. A closer estimate of the exact date of this "calving event" was not possible, due to cloud cover obscuring satellite imagery of the region.

With Iceberg A-68 calving off, it becomes the sixth largest iceberg ever recorded in the satellite era, at 5,800 square kilometres in size. That's larger, in total surface area, than Prince Edward Island.

Comparison between Iceberg A68 and Prince Edward Island. Credit: NASA Worldview/Google/Scott Sutherland

Based on Brigham Young University's Antarctic Iceberg Tracking Database, Iceberg B-15, which calved off from the Ross ice shelf in March 2000, is still the largest iceberg in the satellite record, at 11,000 sq km. The largest iceberg from the pre-satellite record books was reported off of Scott Island in 1956, by the crew of the USS Glacier, and was measured at 333 km by 100 km in size (roughly three times larger than B-15!). While the size measurements of the 1956 iceberg are not considered to be as reliable as those taken by satellite imagery, it was likely still larger than any others seen since.

What happens next for this trillion metric tonne chunk of ice?

At the moment, Antarctica is in the darkness of winter, and the seasonal sea ice around the continent is still growing towards its yearly maximum. The sea ice is not static, however, as the wind-driven currents in the western Weddell Sea (near Larsen C and A-68) are pushing sea ice past the iceberg, in a northerly direction. Exact how the sea ice interacts with the iceberg will likely have a large effect on what happens to A-68 next, at least in the short-term.

While impacts from the sea ice on different parts of the iceberg could simply have it rocking back and forth in the divot it created in Larsen C, satellite images taken since it calved off seem to indicate that the southern end of the iceberg is currently pulling away from the ice shelf. This could be friction from the sea ice dragging past it, and also ice impacting and pushing on its southern tip, possibly displacing A-68 out of that divot. Further observation is needed to know for sure, though.

When A-68 does exit that divot, whether due to the sea ice or after it has access to more open water, the Weddell Gyre - a clockwise circulation that exchanges water between the Sea and the Southern Ocean - will likely pick it up and pull it along the coast towards the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, and possibly out into the Southern Ocean.

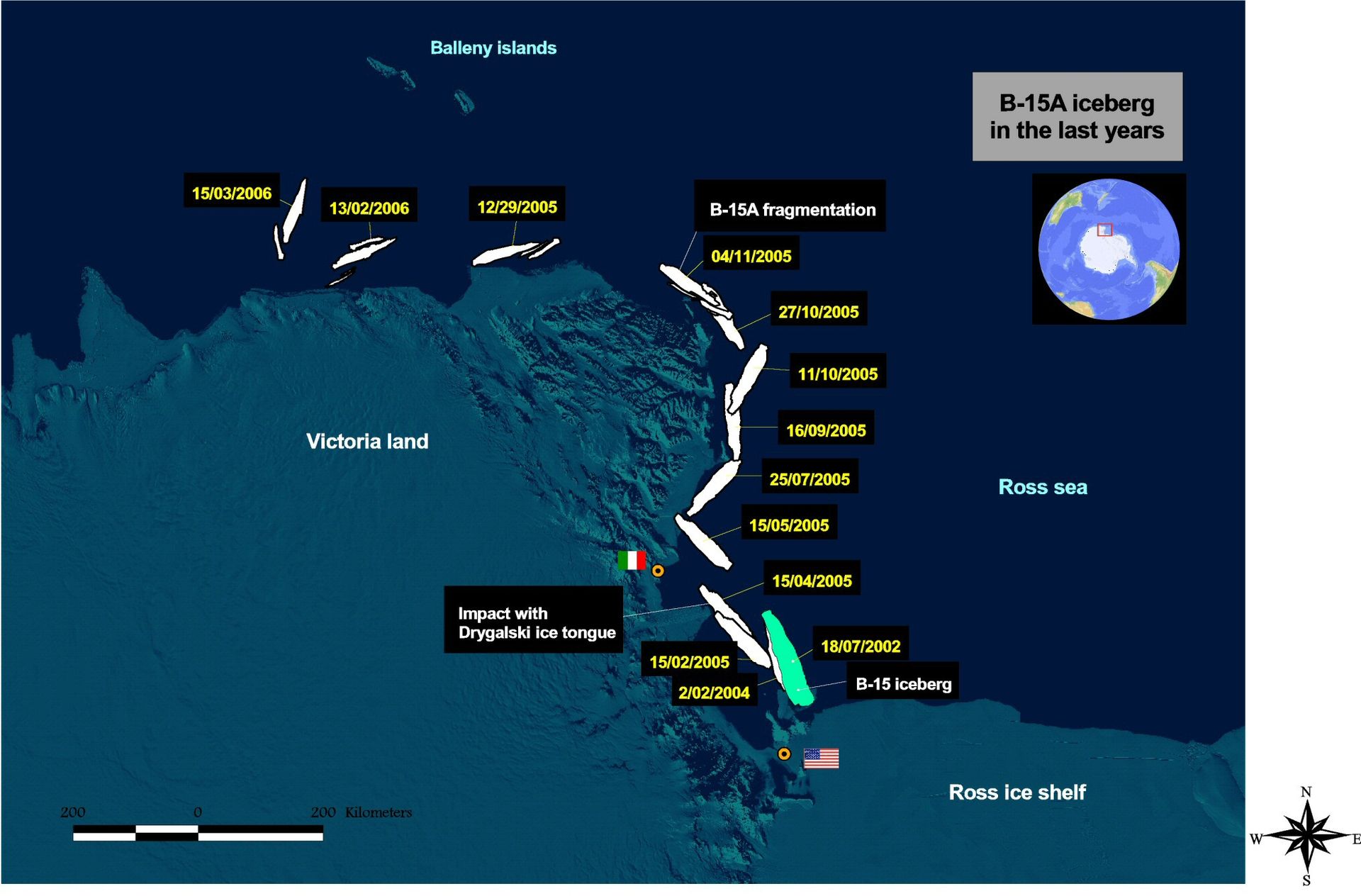

It's unlikely to get away unscathed, however. Just look what happened to Iceberg B-15, as it drifted away from the Ross ice shelf in the years after it calved off.

Iceberg B-15, between 2002 and 2006. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

In total, B-15 broke up into 28 pieces in the 17 years since it formed, four of which are still tracked by the U.S. National Ice Center (USNIC). The largest of these remaining pieces, B-15T, is roughly 46 km long by 11 km wide, and according to USNIC records, is currently located off the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula.

With the rugged coastline to the north of Larsen C, and with the inlets and bays largely open due to the loss of Larsen A and B, this iceberg could have a bumpy ride ahead of it in the months and years to come. This would likely fracture it into many smaller pieces, just as we saw with B-15. These pieces could get trapped in any of the inlets to the north, or they could become caught up in the currents surrounding Antarctica, but given where most of the icebergs in that area end up, their likely destination would be the open waters of the Southern Ocean.

Iceberg A-68 is sure to be monitored for some time, as it, or at least several of the smaller chunks it breaks down into, could be around for decades.

Is this climate change?

Larsen C was once one of four ice shelves that existed along the east coast of the Antarctic Peninsula. The Larsen A and Larsen B ice shelves, which were farther north of Larsen C, closer to the tip of the peninsula, are gone now. Both experienced similar large calving events in the past, and the rest of those two ice shelves quickly retreated in the aftermath - Larsen A in 1995 and Larsen B in 2002. Larsen D, which is farther south towards the main continent, remains intact and largely stable, however it is very narrow, and is more protected by the rugged shoreline of that part of the peninsula.

Now, there's no reason to say that the formation of Iceberg A-68 had anything directly to do with global warming or climate change. Iceberg calving is a natural process of these ice shelves, which formed in the first place due to glacial ice on land being pulled down-slope by gravity towards the shoreline. As the glacial ice continued to flow, it pushed the leading edge of the ice out over the water, where it floated on top of the denser water beneath it. Even with the ice shelf more or less fully formed, continued pressure from the glacial flow, as well as friction with the sides of the bay or inlet it resides in, interaction with the water beneath it and with the currents along its edge, all puts strain and stress on the ice. This can cause cracks to form, which leads to chunks breaking off along the leading edge.

Where global warming and climate change come in is the rate at which all of this happens, especially due to the warming ocean water underneath that weakens the ice shelf from below.

"The Antarctic Peninsula has been one of the fastest warming places on the planet throughout the latter half of the 20th century," Dan McGrath, a glaciologist at Colorado State University, told NASA Earth Observatory. "This warming has driven really profound environmental changes, including the collapse of Larsen A and B, but with the rift on Larsen C, we haven’t made a direct connection with the warming climate. Still, there are definitely mechanisms by which this rift could be linked to climate change, most notably through warmer ocean waters eating away at the base of the shelf.”

Does the loss of Iceberg A-68 portent the doom of the Larsen C ice shelf? Perhaps not.

"The remaining 90 percent of the ice shelf continues to be held in place by two pinning points: the Bawden Ice Rise to the north of the rift and the Gipps Ice Rise to the south," Chris Shuman, a glaciologist with the Goddard Space Flight Center and the University of Maryland, told NASA. “So I just don’t see any near-term signs that this calving event is going to lead to the collapse of the Larsen C ice shelf. But we will be watching closely for signs of further changes across the area."

So, unlike the Larsen A and Larsen B ice shelves, Larsen C may endure for awhile longer.

Sources: NASA Earth Observatory | NASA | US National Ice Center | Antarctic Iceberg Tracking Database