Chinook winds and Alberta weather

Meteorologist

Thursday, January 8, 2015, 7:08 PM - Alberta – the province where you can experience all 4 seasons in a single day (how’s that for an Alberta slogan?) If you live there, you’re no stranger to this, but allow me to enlighten the rest of the country.

Snow storms in the summer, radical 40 degree temperature changes in the winter – Alberta, you really do have it all, don’t you? And this past week has been proof of it. Let’s re-cap it, shall we?

The first week of 2015 brought dramatic temperature differences as an extremely cold, dense Siberian high pressure system traveled across the Arctic. It slid down and blasted the Prairies with another dose of temperatures 15-20 degrees below their normal – a pattern we occasionally see in winter. (To get a sense of the depth of this cold air so far in 2015, refer to Figure 1, below):

This past Sunday, Calgary reached a daytime high near -20°C (normal runs around -3 degrees Celsius). On Wednesday, the day started off at -15°C, but Calgary rose up to nearly +10°C that afternoon. So what caused this blissful reprieve from winter? A quick lesson in geography and your favourite theory (parcel theory, of course!), and you’ll have a much better understanding.

The infamous Rocky Mountains line western North America, towering from extreme northern British Columbia all the way south through to New Mexico in the United States. This mountain range plays a significant role in the modification and generation of weather systems. As warm, moist Pacific air meets the B.C. coast from the west, it encounters a series of mountain chains, the last of them being the Rockies. Once this air reaches its final vertical road block, the only choice it has is to rise along the mountain side.

Back to our science class days, we remember that as air rises, it expands and cools (a term we call adiabatic cooling). Crudely speaking, the air cools to the point where the moisture condenses into water droplets and the majority of it falls out either as snow or rain as it ascends to the top of the mountain. Once it’s at the peak, the forcing disappears and the now cooler air is free to do what it wants: begin its descent down the leeside of the mountain, where the opposite effect occurs (adiabatic warming). The air experiences gravitational compression. This compression is what causes the air parcel to warm up. Thus a warm, dry air mass is created on the east side of the mountain – a phenomena we refer to as a Chinook wind (refer to Figure 2):

Forecasting Chinook Winds

Now you’re probably thinking all westerly winds should produce a Chinook effect, and since our generic weather pattern has winds flowing west to east (you’ve done your research!) we would experience this dramatic occurrence more often than observed. While you wouldn’t be wrong to think this, there are a few other considerations besides wind direction that must be taken into account when determining whether you’ll be Chinook’ed that day.

1. Most low pressure systems coming in from the west are destined to encounter the Rockies on their eastward trek, yet many of them don’t have the strength to make it over the peak and re-form. Ideally, we need the wind to be flowing perpendicular to the mountain range (westerly flow) and traveling nearly 40 km/h or greater to overcome the mountainous barrier.

2. Another factor is what type of air mass is already in place over Alberta. In a set up where a cold high pressure system is over the Prairies, the winds flow in a clockwise fashion around the high pressure centre and easterly winds will keep the warm air at bay along the slope. Pulling again from our early education we remember that warm air rises and cold air sinks; therefore, it’s no surprise that dense cold air will not want to budge and any warm air that makes it over the peak will normally run over top of it. What we need now is a forcing mechanism and enough momentum to accelerate the warmer air to the surface and essentially push out the cold.

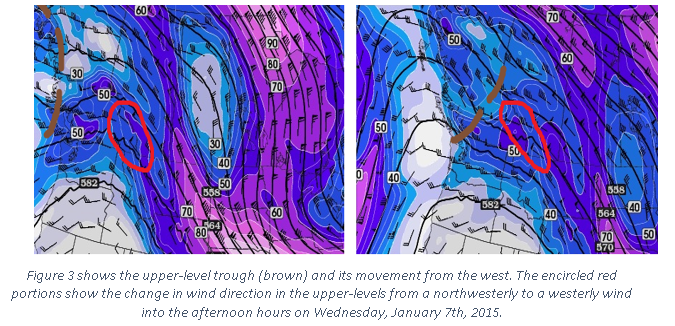

3. This past Wednesday, a large ridge in the jet stream over the B.C. coast was in place and it propelled a small scale upper-level trough across the Rockies, creating strong winds that changed from a north-westerly component to the desirable westerly wind (remember our first point). This supplied the needed momentum for the winds to reach the surface and force out the cold temporarily into South-Western Alberta (Figure 3).

4. There needs to be a temperature inversion at or above the mountain top. Simplistically, an area where the air temperature increases with height, as opposed to its normal decreasing with height. This ensures that the air that rises on the windward side of the mountain will be trapped and won’t be able to continue to rise – essentially forcing it back down towards the surface.

5. Last but not least, the air that does make it to the other side will form a weak surface low pressure and where this forms makes all the difference. Keeping in mind that winds circulate in a counter-clockwise manner around the centre of a low, if you are found south of the centre, you will continue to experience the westerly warmer chinook winds. However, if you are placed north of the centre, welcome in brisk north to north-easterly winds and say goodbye to your Chinook’d day. To put things into perspective, refer to Figure 4.

NEXT PAGE: THE GREATEST TEMPERATURE EVER RECORDED FROM A CHINOOK:

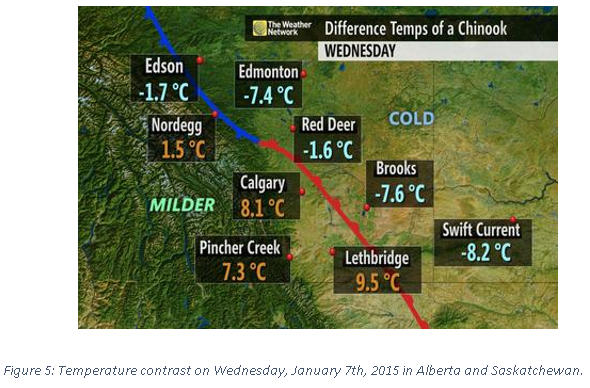

Although I’ve already mentioned the balmy temperatures on Wednesday, the interesting part is the drastic temperature gradient observed from western to eastern Alberta seen in Figure 5 (Notable: Lethbridge to Brooks, nearly a 20°C temperature difference over ~100 km distance). On a fun side note, the greatest temperature change ever recorded from a Chinook wind was back in 1962 where the temperature in Pincher Creek rose 41°C (from -19°C to +22°C) in just one hour. Weather, you are so impressive!

So now that we’ve gone through the key factors in what produces this phenomena, what comes next? Looking at the above picture, it’s obvious where our next issue lies. The trick now becomes determining the intensity and how far the warm frontal boundary will extend.

When attempting to predict tight temperature gradients days in advance we encounter a few issues. Interestingly, future weather for Canada will be dependent on what’s currently happening thousands of kilometers away. Most of the uncertainty in our forecast arises from our lack of available observations (especially over the ocean) and how the mathematics in our models are simply approximations and do not produce exact solutions.

As we push the technology to glance at the long-range, our confidence deteriorates, especially when considering small-scale features (such as Chinook winds) – they simply aren’t resolvable. Think of it like glancing into the distance with a terribly prescribed pair of glasses: you can see something is there, but the details are fuzzy.

However, once we reach a day or two before the event, our sight has improved and we generally have a better grasp since our high-resolution weather models are now at our disposal. For example, these models operate with a 4km or greater resolution, and it’s much easier to model these smaller-scale events to see where the extremes may lie, given they initialize well to the current environment.

At the end of the day, predicting a Chinook event accurately still boils down to the skills of an experienced forecaster. It’s all about pattern recognition and knowing the power and weaknesses of our weather models.