Acid rain: An environmental success story? Well, sort of

Credit: Wikipedia

Meteorologist/Science Writer

Wednesday, February 4, 2015, 12:30 PM - Back in the '70s, '80s and '90s, when the world was mobilizing to heal the damaged ozone layer, and the dire warnings about global climate change were really just starting, acid rain was making ominous headlines in the news. These days, we rarely hear anything about it, so what ever happened to this issue? Is it over? Did we solve that one?

Well, sort of...

Acid rain is caused when gases like carbon dioxide, nitrogen dioxide and sulphur dioxide - which can be naturally-occurring but are also released by burning fossil fuels like coal and oil - dissolve in water vapour and water droplets in clouds.

|

|

When combined with water, these gases (either directly or through a sequence of reactions) form into carbonic acid, nitric acid and sulphuric acid, respectively, which fall with the rain and end up in groundwater, lakes, rivers and streams.

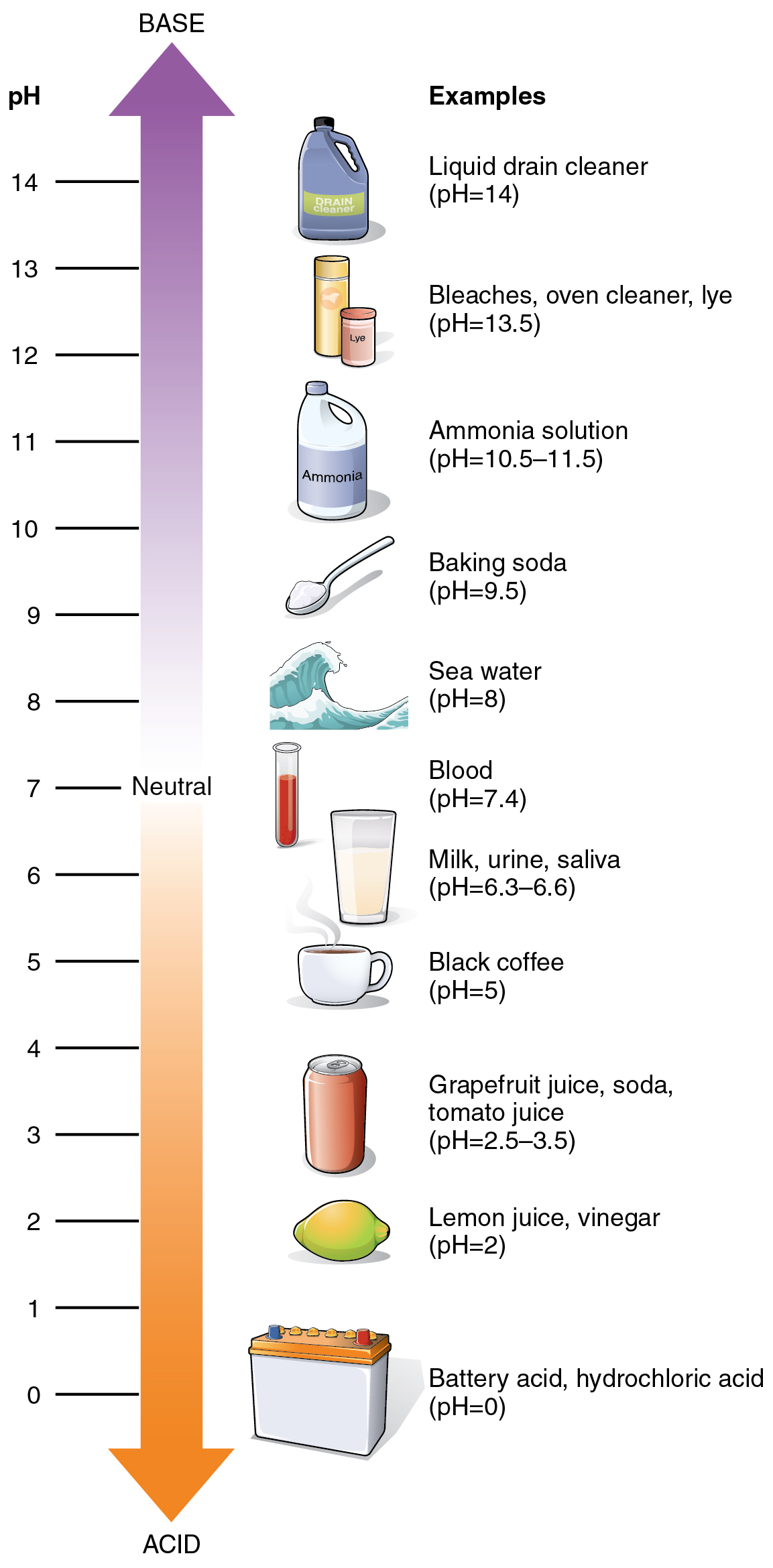

Even the cleanest rainwater can be ever-so-slightly acidic. Read on the pH scale (presented to the right) rainwater can come in anywhere between 5.5 and 6.5. This is generally fairly harmless to life and nature has ways of dealing with these slightly acidic levels (both biologically, and geologically - like through the dissolving of limestone, for example).

However, if the pH drops to less than 5.5, nature can't deal with these levels as effectively. The chemistry of waterways changes. Plants and trees are damaged, producing 'burned out' forests. Fish eggs won't hatch. Insect species die off. Entire aquatic ecosystems can be compromised, resulting in 'dead lakes'. In some cities, statues and buildings made of limestone and marble are being eaten away by the corrosive rain.

In Canada, nowhere were the effects of acid rain more severe and widespread than in the vicinity of Sudbury, Ont., due to the sulphur emissions from the nickel smelting operations there.

"Sudbury is often the poster-child for acid rain," said Professor John Smol, the Canada Research Chair in Environmental Change at Queen's University, in Kingston, Ont.

With the sulphur emissions depositing in the local environment, and the Canadian Shield's lack of any significant limestone buffer, this spelled doom for much of the plant life in the region (save those that could tolerate the acidic soils, like blueberry bushes and trees such as the paper birch).

With the need for action great, the United States and Canada stepped up to impose limits on the amount of sulphur dioxide and nitrogen dioxide being released into the atmosphere by industry and power generation plants.

How did these measures do? As of 2007, the EPA reported that - through the use of a cap-and-trade system - not only had the United States reached their emission targets at least three years ahead of schedule, but they'd done so even more cheaply than expected, with costs coming in at roughly one-quarter what they were originally projected. Environment Canada reports showed similar progress and successes with the cross-border program shared with the United States.

So, the acid rain story is a success story, right?

Not entirely, or at least not yet.

A "sort of" success story

Smol, who co-directs of the Paleoecological Environmental Assessment and Research Laboratory (PEARL), is an award-winning biologist who has been studying the problem of acid rain since the 1980s.

"I tend to refer to it as a success story... sort of," he said in an interview with The Weather Network.

"Compared to some other environmental problems, we caught the worst of it in time," Smol explained, "and we had significant legislation, especially in the early 1990s, that really made a big difference in acid rain. That's one of the reasons we don't hear about it as much these days."

"That's not to say that acid rain isn't a problem," he added. "The rain is still somewhat acidic, but just not as bad as it was."

According to the research of Smol and others, notably for Ontario and Canada at the Dorset Environmental Science Centre, the situation was very bad at the worst of it, and the future was looking very bad as well. However, through action, there have been improvements in the pH levels of rainwater, lake water and ground water, and places like Sudbury are seeing what Smol called 'remarkable' recovery.

While the pH levels of lakes and groundwater returning to a more normal level is certainly a good thing, the problem of acid rain hasn't yet been solved, due to three reasons:

-

The recovery of lakewater pH levels has been slow, and in cases has been going slower than some researchers had hoped,

-

The recovery of the biology of the ecosystems is proceeding very slowly, which is often the case in these situations, and this is being worsened by other stresses, such as climate change, and

-

There have been unanticipated impacts on the environment.

|

|

"There were things happening with acid rain 'under the radar', that we weren't even thinking of," said Smol. "One of the things that was happening was that calcium in many of these areas was declining - what we call aquatic osteoporosis."

With calcium so important - to plant, animal and insect life in the lakes - this long-term decline was having a big impact, especially on some of the smallest forms of life in the ecosystem, namely tiny, plankton-like crustaceans called Daphnia, aka 'the water flea'.

"You may say, 'who cares about a water flea?'," said Smol, "but they are an important part of the food chain, and they eat algae."

![]() DID YOU KNOW? Algae can be a big problem in lakes, as uncontrolled blooms can consume all the oxygen in deep water zones, creating dead-zones where other species cannot survive.

DID YOU KNOW? Algae can be a big problem in lakes, as uncontrolled blooms can consume all the oxygen in deep water zones, creating dead-zones where other species cannot survive.

With the decline of calcium, which is vital to these organisms to survive, it came down to a competition between different species revolving around which of them could tolerate the lowest levels of calcium. One species that has been winning out in this competition is the jelly-coated Holopedium glacialis.

|

|

"What's the consequence of this?" Smol said. "For one it's a much poorer food item, because it's covered in this jelly, and it's bigger, so more things can't eat it." That produces a problem where the abundance of food near the bottom of the food chain is reduced, impacting on recovery rates.

"Secondly," Smol continued, "there are even records now of it blocking water intake valves."

Smol and his colleagues have studied this 'jellification of lakes' over time, as one of the unforeseen consequences of the acid rain problem.

"This is a sequence of stories that goes back in time," he said, "and it shows the unexpected consequences, that we never would have thought of, that are actually now coming out as negative impacts."

Lessons to be learned?

As we see, although there have been overall improvements regarding the issues surrounding acid rain, it can be the problems that we don't, or can't foresee that produce the longest-term impacts.

"There are some lessons there to be learned for climate change," said Smol, "that it's the unexpected consequences we don't even think about that are causing problems, and that we're usually quite optimistic about these issues."

It's often lost in all the discussions, but the dire warnings coming out from the various reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), including the latest one, have always represented the lowest common denominator of expected consequences. Thus, all the worst-case and best-case scenarios from the research are examined, and the scenario that everyone can agree on is the one that gets presented.

This reflects the same kind of optimism that Dr. Smol discussed, but it's very likely that the true effects will fall somewhere in the middle, between the best and worst cases, and there will very likely be unforeseen consequences from climate change, which could turn out to be some of the worst, or longest-term effects.

Still, by acting to reduce emissions, and thus curb acid rain, we avoided a situation much worse than we have now.

Similar action on climate change will still include unknowns, but the world we end up with by avoiding or delaying action can only be worse than what will result from reducing carbon dioxide emissions now.

RELATED VIDEO: Climate Change in Canada