How volcanic eruptions can change hurricane season for years

Considering how closely Earth's systems -- be they atmospheric, oceanic, or geological -- are linked, it makes intuitive sense that volcanic eruptions have some impact on the formation of hurricanes, but until a recent study, scientists weren't sure how the two interacted.

Visit our Complete Guide to Spring 2019 for an in depth look at the Spring Forecast, tips to plan for it and much more

The study, led by researchers at The University of Quebec in Montreal and Columbia University, shows for the first time how large volcanic eruptions have impacts that echo through not just the tropical cyclone season following the eruption, but for years afterward.

"This is the first study to explain the mechanism of how large volcanic eruptions influences hurricanes globally," Suzana Camargo, one of the authors, said in a release from Columbia University.

Why has it taken so long to untangle the puzzle? A lot of it comes down to timing. While we've had the computing power to monitor and study the problem for a while, most of the major eruptions in recent history have occurred during El Niño or La Niña events (the El Niño Southern Oscillation, or ENSO), which themselves impact tropical cyclone seasons around the globe.

This study -- based on sophisticated simulations -- sought to isolate major eruption events from any ENSO impact, and a distinct pattern emerged.

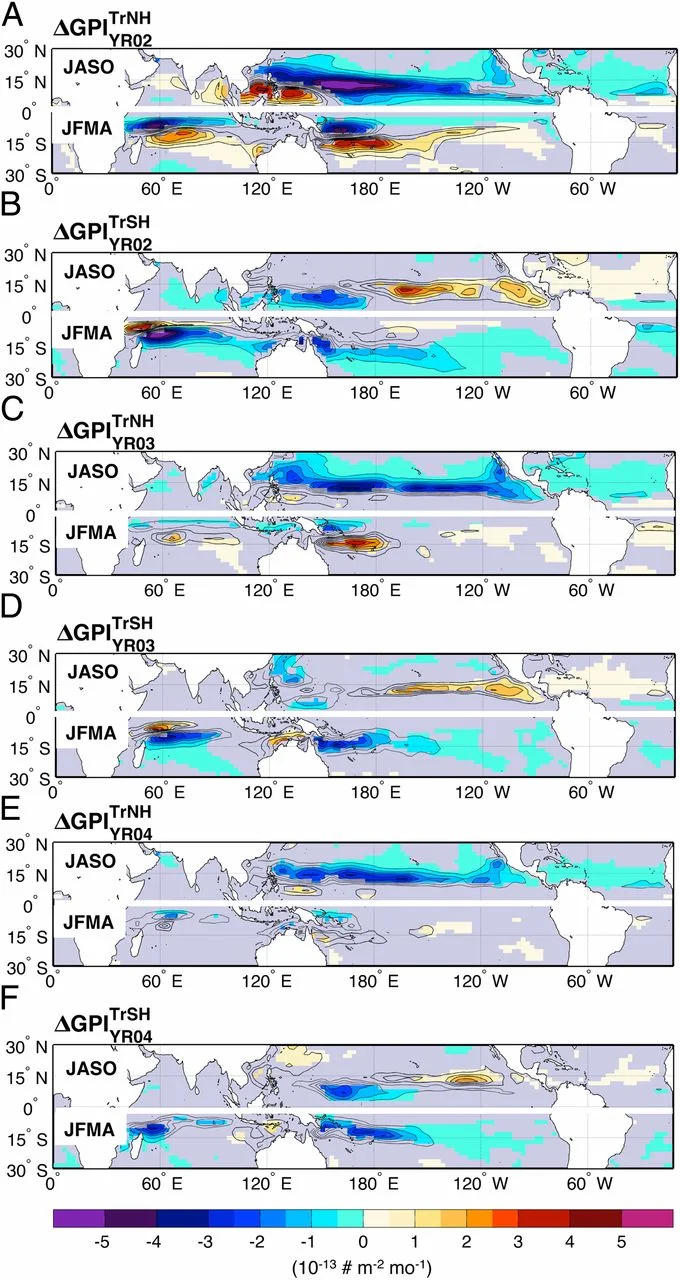

*The above image shows the change in potential cyclone intensity -- or the strength of storms that develop -- for eruptions in the Northern Hemisphere (top) and in the Southern Hemisphere (bottom). Image courtesy PNAS. *

The team found that large eruptions in either the northern or southern hemispheres served to push the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) away from its usual position -- further into the southern hemisphere in the case of a northern hemisphere eruption, and the opposite for an eruption south of the Equator.

The ITCZ is the band near the Equator where the trade winds converge, known as the 'doldrums' -- so named by sailors because the surface winds are calm at this convergence point. This region plays a key role in the formation of tropical cyclones when the boundary drifts north or south out of the doldrums and into regions more favourable for cyclone development, be they Atlantic hurricanes or Pacific typhoons.

"A large eruption in the tropical regions of the Northern Hemisphere leads to a southward shift of the Intertropical Convergence Zone. This results in an increase in hurricane activity between the Equator and the 10ºN line, and a decrease further north. The zone's southward shift has further effects in the Southern Hemisphere, causing a decrease in activity on the coasts of Australia, Indonesia, and Tanzania, while Madagascar and Mozambique experience an increase." Columbia University Earth Institute

DON'T MISS: Our country is warming two times faster than the rest of the planet. The Weather Network and Canada's leading experts on climate bring you 2xFaster, an exclusive series premiering Tuesday, April 16.

More succinctly, a major eruption in the northern hemisphere pushes the ITCZ south, and the hurricanes go with it. The reverse is also true.

More than that, the effects lingered for four years following the eruption, meaning even after the volcano has quieted, the tropical cyclone season was still altered.

Changes in GPI for TrNH and TrSH experiments relative to the no-volcano reference simulations for the second (A and B), third (C and D), and fourth (E and F) TC seasons (JASO in the NH; JFMA in the SH) following the eruption. Image courtesy PNAS.

With tropical cyclones generating tens of billions of dollars in damages every year, improved forecasting is one key to lessening the blow from future disasters. The more we can understand about the ingredients that go into determining the evolution of the storms -- be they volcanic eruptions or strong El Niño events, the better future forecasts will be.

Sources: PNAS | Columbia University | Science Alert |