Space-time ripples may point to black hole swallowing a neutron star

Astronomers detect gravitational waves that may point to a colossal collision

Did you feel that tiny wobble in the fabric of spacetime? It happened just a week ago, according to astronomers working to detect gravitational waves.

Scientists working with the LIGO and Virgo gravitational wave detectors say that their instruments picked up what could have been the effects of a black hole pulling in a neutron star.

Update: Further study into this event has revealed that this was more likely the merger of two black holes, rather than a black hole and a neutron star. Definitive evidence of a black hole-neutron star merger remains ellusive.

A black hole is essentially a bottomless pit in spacetime, from which nothing can escape, even light. A neutron star is one of the densest forms of matter known - the remnant of a dead star that packs more mass than is contained in our Sun into a compact sphere roughly 10-20 kilometres across.

A dense neutron star spirals in towards the maw of a black hole. Credit: Carl Knox/OzGrav ARC Centre of Excellence

While gravitational wave astronomers have already logged the collision of two neutron stars, and the merger of two black holes, if confirmed, this would be the very first detection of a black hole devouring a neutron star.

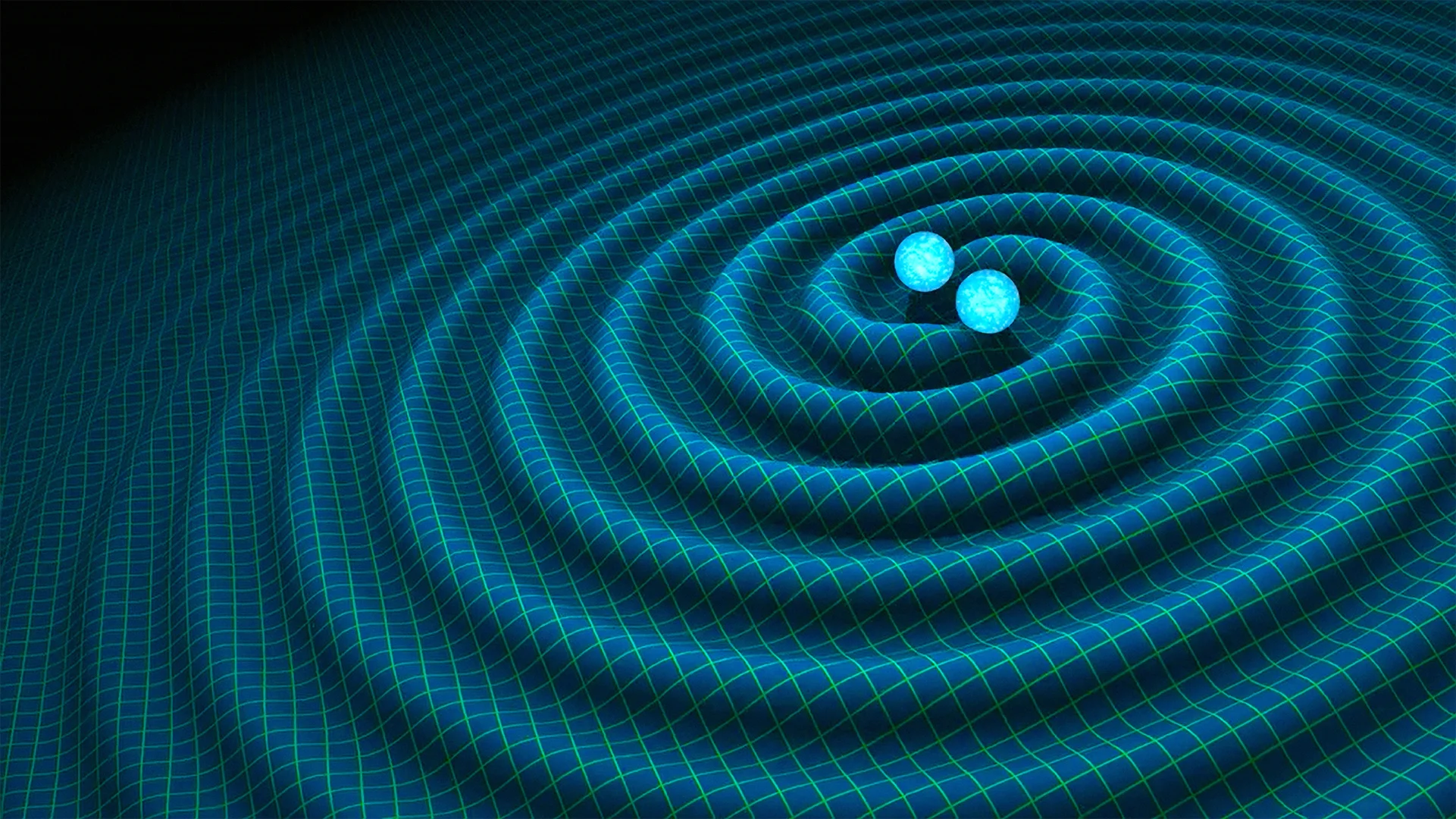

Two neutron stars spiral in towards one another in this artist impression, setting off ripples through spacetime known as gravitational waves. Credit: R. Hurt/Caltech-JPL

According to Australia National University, "Professor Susan Scott, from the ANU Research School of Physics, said the achievement completed the team's trifecta of observations on their original wish list."

The ripples in spacetime that passed through us were so tiny that we'd never notice them. You need laser beams bouncing down and back tunnels three to four kilometres long just to see their effects.

The LIGO Hanford observatory, in Washington State. Credit: Caltech/MIT/LIGO Lab

The two LIGO observatories in the United States and the Virgo gravitational wave detector in Italy detected these gravitational waves on August 14, 2019.

The neutron star merger detected nearly two years ago was picked up by a host of other telescopes and observatories, as it set off a bright 'kilonova' explosion that sprayed out gamma rays and other high energy light that was detected shortly after the gravitational waves swept past.

The black hole merger, on the other hand, was invisible except for the spacetime ripples that expanded outwards from it.

In this case, although telescopes scanned the region of the merger after the gravitational waves were detected, Professor Scott said that nothing was spotted to confirm it.

That is not necessarily a bad thing, however.

"Although we've not seen anything yet, we'll be able to learn a lot about the light we've not seen," Maria Drout, a University of Toronto astrophysicist who was part of the optical detection team for this merger, told CBC News. "There are some predictions that say you should get light out of systems like this and some that say you shouldn't. So this is this actually very informative."

The astronomers are still working on confirming exactly what they've detected, but based on the apparent masses of the objects, it matches what they expect from a black hole-neutron star merger.

"However, there is the slight but intriguing possibility that the swallowed object was a very light black hole - much lighter than any other black hole we know about in the Universe," said Professor Scott. "That would be a truly awesome consolation prize."

So, this is really win-win for science!

Sources: Australian National University | CBC News