Young Jupiter likely gobbled up millions of planetoids

Astronomers made a surprising discovery inside the solar system's largest planet.

New research suggests that Jupiter contains the remnants of numerous planetoids that it consumed as it grew in the early solar system.

Jupiter is the largest and most massive planet in our solar system, tipping the cosmic scales at over 317 times the mass of Earth. Most of its bulk is made up of just two elements — hydrogen and helium. However, a small percentage of the planet is composed of heavier elements, all of which astronomers group together into the category of metals.

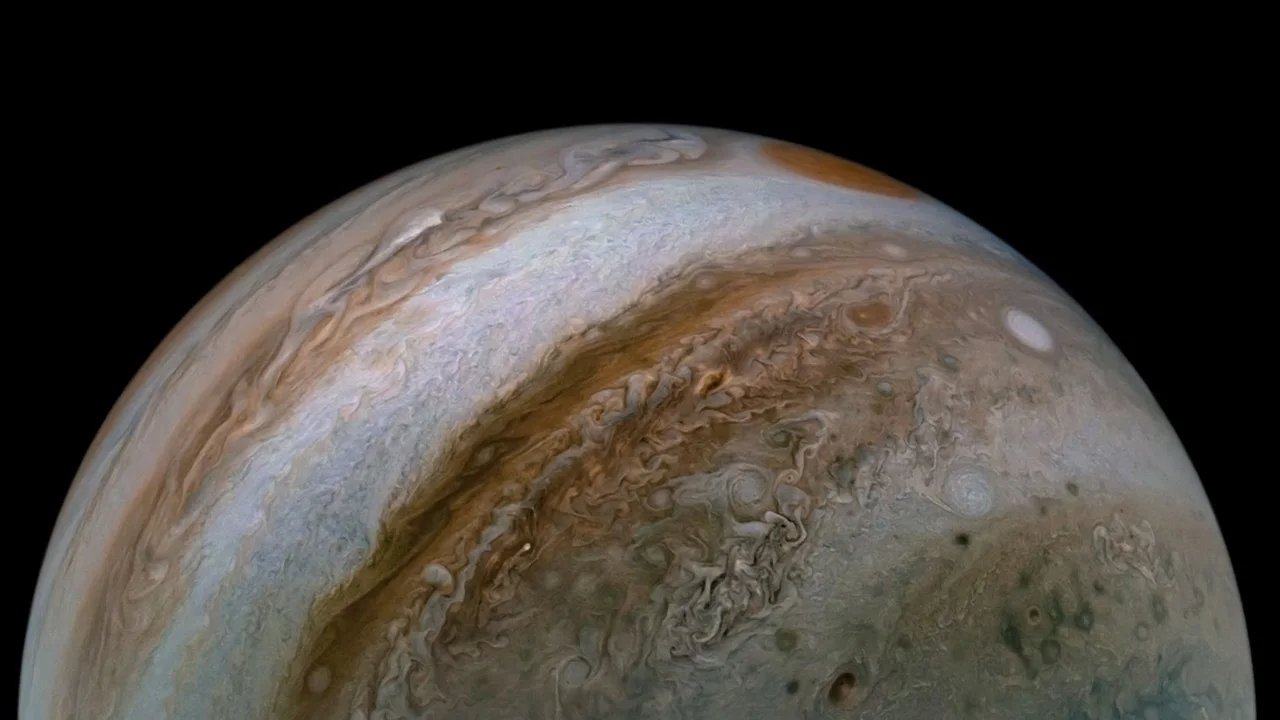

This artist impression shows dark scars in Jupiter's clouds due to shards of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 impacting the planet in 1994. Credit: ESO/M. Kornmesser/NASA/ESA

SEE ALSO: It’s a bird. It’s a plane. It’s the best products for stargazing this summer

This same distinction is used in stellar astronomy, where a star is described as having a specific metallicity, which refers to the amount of stuff in the star that is not hydrogen or helium.

New research has used data from NASA's Juno probe to investigate Jupiter's metallicity.

As Juno orbits around Jupiter, it makes periodic close passes over the planet's cloud-tops. During each of these passes, the spacecraft keeps careful record of the gravitational pull it experiences due to the material underneath it. This gives researchers an idea of exactly how much stuff is under Jupiter's clouds in different regions of the planet.

Using this data, an international team led by Yamila Miguel, from the Dutch national expertise institute for scientific space research (SRON) and the Leiden Observatory, constructed computer models of Jupiter’s interior to account for what Juno recorded.

Their study revealed some unexpected details about the massive gas giant.

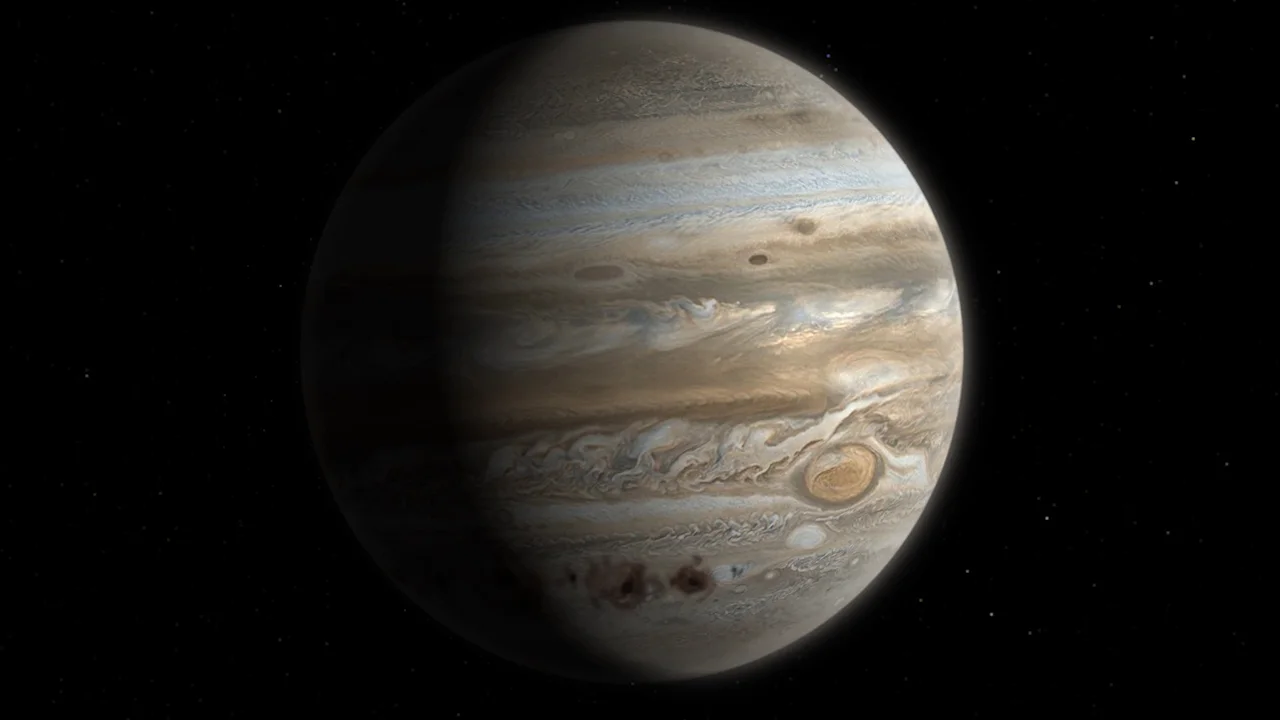

This view of Jupiter's cloud tops was taken by NASA's Juno spacecraft as it made its 31st close-pass around the planet. Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS, processed by citizen scientist Tanya Oleksuik (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0)

DON'T MISS: Overlapping meteor showers put on a show in the night sky this summer

Firstly, the distribution of the metals within Jupiter is not uniform. Instead, they are more concentrated the deeper into the planet you go. While heavier elements do tend to sink towards a planet's core, this discovery is unusual because it was assumed that the motions of Jupiter's atmosphere would cause the metals to be more evenly distributed.

"Earlier we thought that Jupiter has convection, like boiling water, making it completely mixed," Miguel said in a SRON press release. "But our finding shows differently."

Secondly, the total amount of Jupiter's metal content is somewhere between 3 to 9 per cent of the entire planet, or roughly equivalent to 11-30 times the mass of Earth. That's a lot of heavy elements for the planet to consume in a relatively short time.

"There are two mechanisms for a gas giant like Jupiter to acquire metals during its formation: through the accretion of small pebbles or larger planetesimals," Migel said.

Planetesimals (aka planetoids) are solid chunks of rock and/or ice that formed in the early solar system. This includes asteroids and comets larger than 1 kilometre across, but smaller than 100 km. Anything larger would be an 'embryonic planet' or 'protoplanet', while objects smaller than 1 km would be considered 'pebbles'.

Watch below: NASA Juno spots exotic SHALLOW LIGHTING on Jupiter

According to Migel, once a 'baby' planet grows massive enough, its gravity tends to snag the smaller pebbles and fling them out of the way. Thus, by the time Jupiter accumulated enough mass to develop its hydrogen-helium atmosphere, its own gravity would have blocked it from consuming these tiny objects.

However, as the researchers note in the paper, their results indicate that Jupiter continued to accumulate heavy elements, in large amounts, while its hydrogen-helium envelope was still growing. So, a significant amount of the planet's metals had to come from larger objects.

"Planetesimals are too big to be blocked, so they must have played a role," Migel said.

So, how many planetesimals has Jupiter eaten?

If we use some typical asteroid masses from NASA, to account for up to 30 Earth-masses worth of metals, Jupiter would have had to gobble up somewhere between a few hundred million larger ones to billions of smaller ones!