Keep watching the skies as Jupiter and Saturn continue their spectacular display

The Great Conjunction may be over, but Jupiter and Saturn aren't done showing off.

On December 21, we were witness to the greatest Great Conjunction seen in nearly 800 years. Keep your eyes on the southwest horizon just after sunset in the week to come, though, as Jupiter and Saturn continue to put on an amazing show.

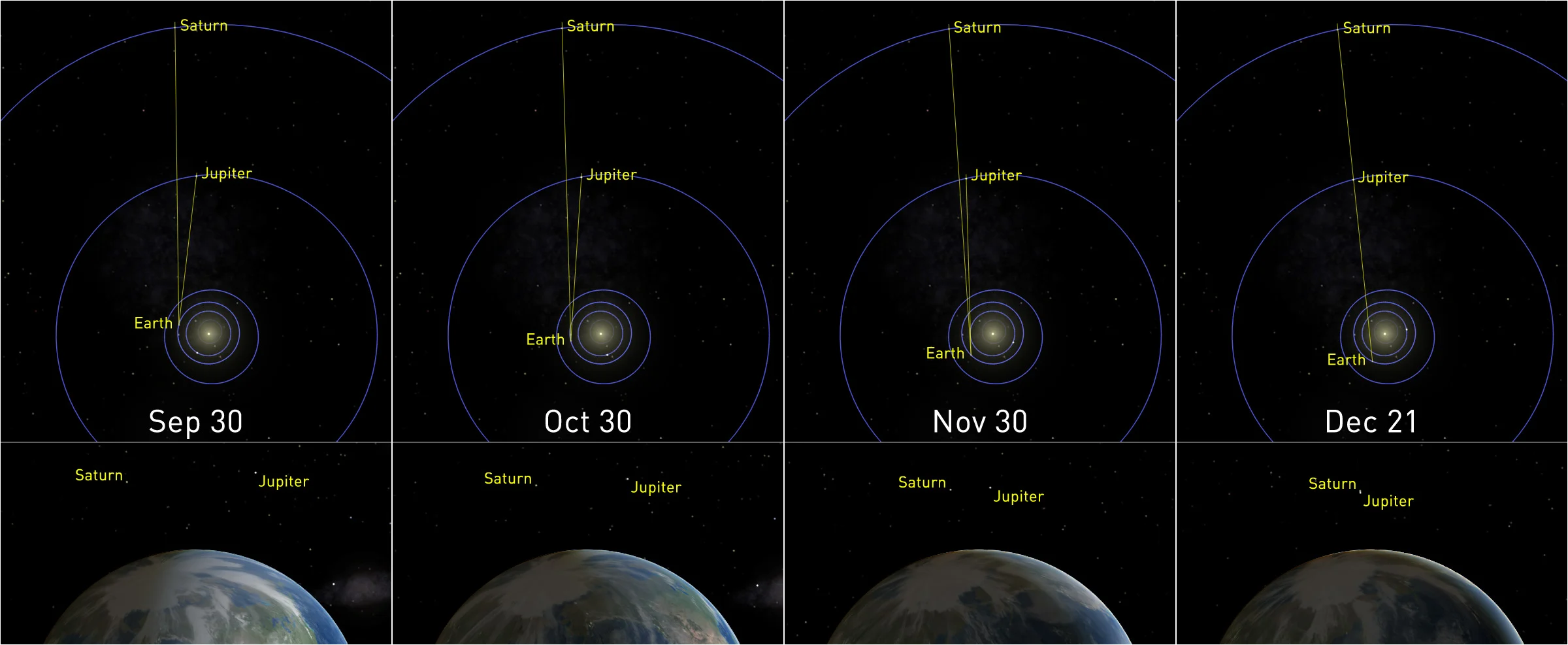

The two most massive planets in our solar system have been a constant sight in our night skies so far in 2020. Throughout the year, the Jupiter and Saturn have appeared to be locked in a slow dance. Drawing closer and closer for the first half of the year, they then pulled apart again until Fall, and then they slowly approaching again, night by night, leading up to the Winter Solstice.

Just hours after the Winter Solstice, on the evening of Monday, December 21, they were so close that, to the unaided eye, they appeared to be merged together into one bright point of light.

This was the Great Conjunction of 2020, and it was the closest such event that we have seen this well in nearly 800 years!

HOW TO SEE IT FROM ANYWHERE

Did you miss the event? If so, the Lowell Observatory — the location from which Clyde Tombaugh discovered the dwarf planet Pluto in 1930 — hosted a live event from Flagstone, Arizona. During the event, they streamed their telescopic view of Jupiter and Saturn, revealing details that would have been impossible to see with the unaided eye. Their event is still available to watch, via the embedded video below:

WHAT'S GOING ON HERE?

As Earth, Jupiter, and Saturn orbit the Sun, we complete one revolution in a year, while Jupiter takes 11.8 years and Saturn takes 29.5 years. Every 19.6 years, from our perspective, the two bright gas giants come into alignment in our sky. Astronomers call these alignments Great Conjunctions.

The positions of Jupiter and Saturn in the solar system relative to Earth, from Saturn Opposition on July 20 to the Great Conjunction on December 21, with the views from Earth. Credit: Celestia/Scott Sutherland

Not all Great Conjunctions are equal, though. During most of these events, the planetary pair just appear reasonably close to one another. Certainly close enough to be notable, but we actually have to go back pretty far to find one comparable to what we saw on Monday night.

"You'd have to go all the way back to just before dawn on March 4, 1226, to see a closer alignment between these objects visible in the night sky," Rice University astronomer Patrick Hartigan said in a press release.

According to Hartigan's records, this year's Great Conjunction had Jupiter and Saturn just one-tenth of one degree apart in the sky. That's 6.1 arcminutes for the astronomers out there. For the non-astronomers, if you hold your hand out at arm's length, palm facing away from you, and extend only your pinky finger up towards the sky, the width of that finger is roughly 1 degree or 60 arcminutes across. So, on the night of December 21, Jupiter and Saturn were about one-tenth of that span apart from one another.

Technically, that made this the closest Great Conjunction since July 16, 1623, when Jupiter and Saturn were only 5.2 arcminutes apart. However, as Hartigan points out, it would have been very difficult to see the 1623 event from Earth without some kind of special equipment. The two planets were too close to the Sun, from our perspective. Thus, that particular great conjunction was lost in the glare of twilight. Going back to March 4, 1226, Jupiter and Saturn were even closer than they come this year (just 2.1 arcminutes apart). Plus, they were high enough above the horizon that anyone would have seen them with the unaided eye.

WHY SO RARELY?

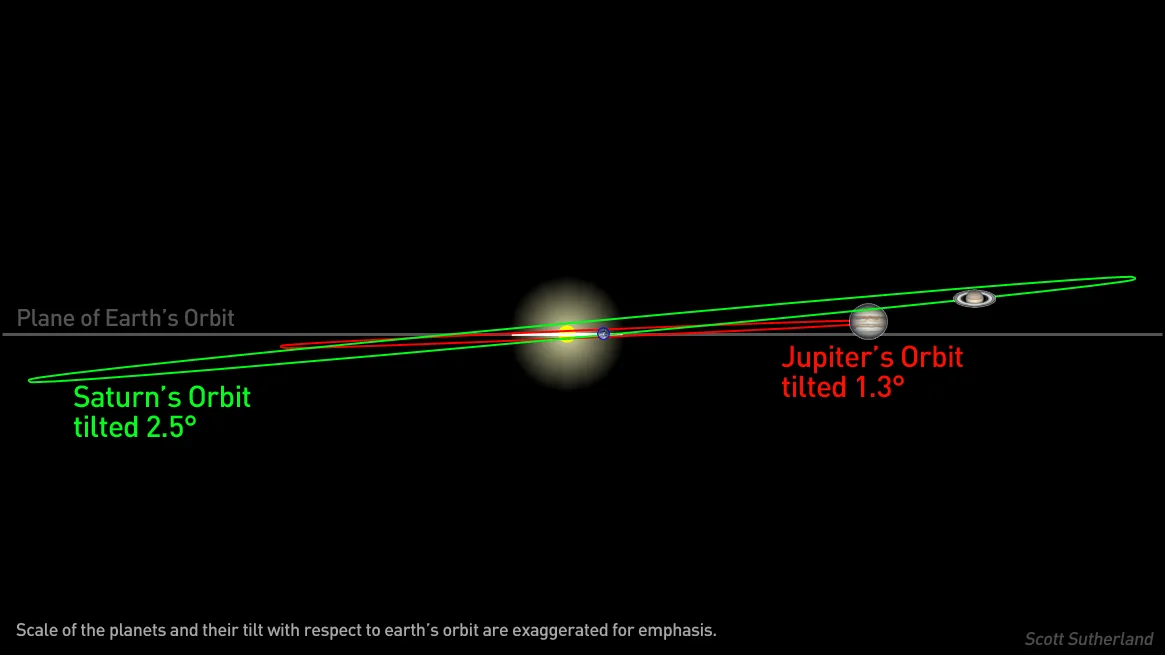

With these conjunctions happening every 19.6 years, one might ask: why don't we see Jupiter and Saturn overlapping every time?

The answer lies in the 'inclination', or tilt, of the two planets' orbits. Jupiter's orbit is tilted by a little over 1.3 degrees compared to Earth's orbit. Meanwhile, Saturn's orbit is tilted by nearly 2.5 degrees. Those are small angles, but when you're talking about planets millions of kilometres away, it's enough to ensure that they only line up this well at specific times.

The inclinations of Jupiter and Saturn's orbits, compared to Earth's orbital plane. As noted in the diagram, the scales have been exaggerated for emphasis. Credit: Scott Sutherland

IS THIS THE CHRISTMAS STAR?

As Jupiter and Saturn were drawning closer and closer in the night sky, some took to calling their impending conjunction "The Christmas Star".

Since the event took place specifically on the Winter Solstice, however, the name is not quite accurate. By Christmas Day, the two planets will be far enough apart that they will be noticeably two objects instead of one — even to the unaided eye. So, to be fair, specifically based on the timing, it would be more appropriate to have called this event a "Solstice Star".

A comparison of Jupiter and Saturn just after sunset on December 21 and December 25. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

Still, this bring up the question: What was the Christmas Star?

In the biblical story of the nativity of Jesus, told in the gospel of Matthew, three Magi, or wise men, were said to have followed a star to where Jesus was born. This may have simply been embellishment on Matthew's part, of course. Since the gospels of Mark and John do not mention the birth of Jesus or the nativity scene, and Luke's version has only shepherds in attendance, there is nothing to support his version of the story.

Still, for some time now, astronomers have been attempting to line up Matthew's account of the Star of Bethlehem with different astronomical events.

Given the precision with which the stars and planets move across our sky, astronomers can effectively 'turn back the clock' to see their locations long ago. If there was some real object (or combination of objects) in the sky at the time, they should be able to find it.

There appears to be some consensus between biblical scholars that Jesus was born in the summer months, sometime between the years 6-4 BC. Some scholars put it sometime between the years 3-2 BC, though.

Looking back to those times, a few candidates have been suggested:

bright Jupiter-Venus conjunctions, in 3 BC and 2 BC,

a supernova (which is known to have produced the binary pulsar PSR 1913 + 16b), in February of 4 BC,

a 'triplet' of Jupiter-Saturn conjunctions in 7 BC, or

an unnamed comet in 4 BC.

In all of these cases, however, the timing doesn't quite match up, or it requires some very specific interpretation or translation of Matthew's account. Without more accurate historical references, or without unearthing some lost text of ancient astronomical records that provides more candidates, it's unlikely we'll ever know for sure.