Earth just had its shortest day in over 60 years

A mysterious wobble of Earth's polar axis may be behind this record-fast day.

The atomic clocks tracking our time just logged the shortest day of the past 60 years.

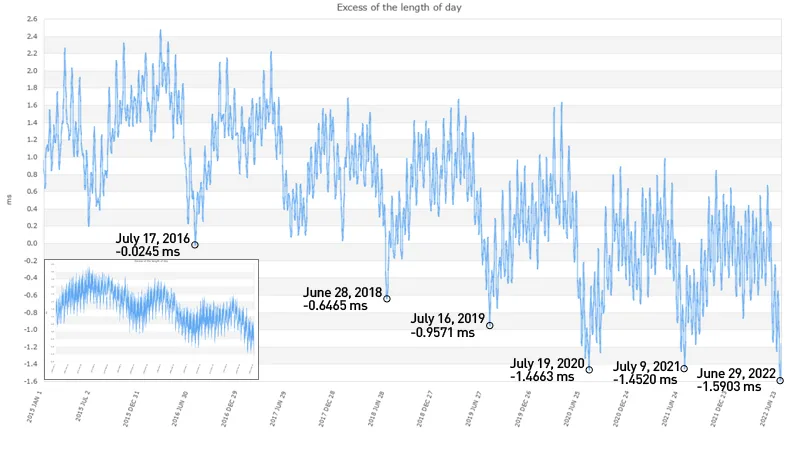

We track our days as all having precisely 24 hours. However, each day varies in length by a tiny amount, measured in milliseconds. Using atomic clocks, the most accurate measure of time we have, scientists track this variation by subtracting the number of seconds in 24 hours (86,400 to be exact) from the total number of seconds recorded during each day.

So far, we have just over 60 years of records, which are kept by the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS). During that time, the length of the day reached a maximum of just over 4 milliseconds longer than the 24-hour standard in the early 1970s. Since then — with a brief pause in the 1980s-1990s, and again through the 2010s — there has been a long-term trend of shorter days.

Now, in the 2020s, days are around an average of 4 milliseconds shorter than they were 50 years ago. About one-third of that change has taken place since 2015.

The length of Earth's days, compared to the standard of 86,400 s per 24 hours, is plotted here, between Jan. 1, 2015, and Aug. 1, 2022. Inset, bottom left, is the entire record from 1962-2022, revealing the general trend over the past 60+ years. Credits: Data from IERS, Plot by l'Observatoire de Paris, Labels by Scott Sutherland

The past three years have seen the three fastest days on record.

June 29, 2022, is now the shortest day we've seen, at more than 1.59 ms faster than the 24-hour standard.

What's Going On Here?

Several factors influence how much of a change we see in the length of our day. The Moon, the Sun and the other planets in our solar system all tug on the planet. The Moon's effect is particularly noticeable in the above graph, as the rapid oscillations in the timing of the length of day. The motions of the atmosphere and the movement of water on and under the planet's surface also play a part. The longer, yearly pattern in the graph is apparently due to these effects. Even the dynamics of Earth's core have a role in setting the timing of Earth's rotation.

The gravitational pulls of the Moon and the Sun have their influence on the length of Earth's days. Credit: NASA

According to TimeandDate.com, Leonid Zotov, a researcher at the Sternberg Astronomical Institute of Lomonosov Moscow State University, says that it may also be related to a periodic motion of Earth's polar axis, known as the Chandler wobble.

"The Chandler wobble is a component of Earth's instantaneous axis of rotation motion, so called polar motion, which changes the position of the point on the globe where the axis intersects the Earth's surface," Zotov told Forbes.

The Chandler wobble was discovered in 1891 by American astronomer Seth Chandler. While it is a tiny motion compared to the size of the planet — less than 10 metres every 14 months or so — it is still something that our technologies (like GPS) need to account for.

The exact cause of the wobble isn't known. However, it likely has something to do with the internal dynamics of Earth's core.

"We are not sure because Earth is a very complex system," Zotov explained, "but I believe it's causing the Chandler wobble to decay and the length of day to decrease synchronously."

The First 'Drop Second'?

We've heard of Leap Seconds. Every year, on June 30 and Dec. 31, there's a chance we will add an extra second to the day. This accounts for short-term variations in the length of the day compared to Universal Time (UTC), and it ensures that our clocks remain synced to our day.

Credit: Scott Sutherland

So far, 27 leap seconds have been added since 1972, with the last on December 31, 2016.

However, if our days continue on the long-term trend of getting shorter, we may eventually need to drop a second from a day to compensate. If so, it would be the first time we've ever applied a 'negative leap second'.

"If acceleration continues, the question of a one second subtraction from Universal Time would become actual," Zotov told Forbes.

We're not quite there yet, though.

Zotov told TimeandDate.com that it's likely we have already seen the shortest day of this year, and thus "we won't need a negative leap second."