Eyes to the skies! Don't miss these beautiful winter astronomical events

Despite the cold, winter is an exceptional season for skywatching and stargazing. Here's what to watch for in our skies.

Clear winter nights often present the best viewing, compared to other seasons, as the air overhead tends to be drier and more stable. Stars, planets and the Moon appear crisper and cleaner as their light encounters less turbulence in the air before it reaches us. The drier air also reflects back less of the light pollution produced by our urban centres. So our skies tend to be darker, allowing us to see more stars and more of the dimmer meteors during annual meteor showers.

So, stay warm when you go out skywatching this coming season, and don't miss these great events.

QUICK LIST

December 21 - Winter Solstice and Great Conjunction

December 21-22 - Peak of the Ursid Meteor Shower

January 2 - Earth at perihelion (closest to the Sun)

January 2-3 - Peak of the Quadrantid Meteor Shower

January 10 - Jupiter, Saturn and Mercury together at dawn

January 11 - Venus pairs with the Crescent Moon

January 24 - Saturn Conjunction

January 29 - Jupiter Conjunction

February 18 - 1st quarter Moon near Mars

March 1 - Zodiacal Light after evening twilight, western sky for two weeks

March 5 - Mercury and Jupiter nearly overlap at dawn

March 19 - Mars teams up with the Moon

March 20 - Equinox

Visit our Complete Guide to Winter 2021 for an in-depth look at the Winter Forecast, Canada's ski season, and tips for planning for everything ahead!

JUPITER, SATURN AND THE GREAT CONJUNCTION

On December 21, watch the western sky in the hours just after sunset. As twilight fades, you will see a very bright 'star' emerge, very low on the horizon. However, that is no star. That is actually the planets Jupiter and Saturn, seemingly merged in an event known as a Great Conjunction.

Jupiter and Saturn have been a constant sight in our night skies so far in 2020. During the Spring and the first half of Summer, these two bright planets were seen drawing closer together as they approached their 'Oppositions' with Earth. An Opposition is where a planet is on the exact opposite side of Earth from the Sun. Afterward, the two gradually pulled away from one another until late September, and since then, they have been slowly approaching again, night by night.

Just hours after the Winter Solstice, they will line up almost perfectly, in the closest Great Conjunction we've seen this well in nearly 800 years!

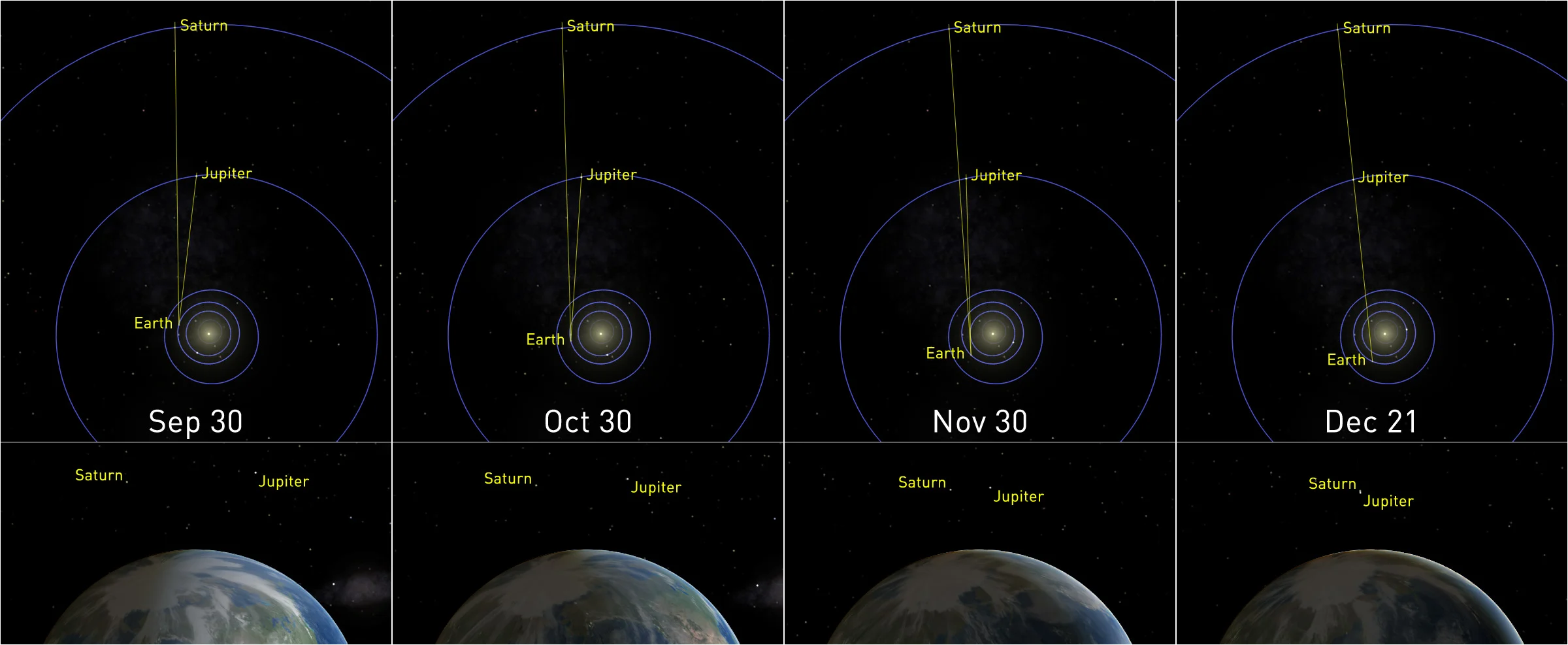

Jupiter and Saturn, in the southwestern sky, draw closer and closer between September and December until they appear to merge. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

So, what's going on here? As Earth, Jupiter, and Saturn orbit the Sun, roughly every 20 years, the timing works out to bring the two bright gas giant planets into alignment in our sky. Not all Great Conjunctions are 'created' equal, though. For most, the pair are reasonably close to one another. The event is certainly enough to be noticeable, but we have to go back pretty far to find one comparable to what we're going to see in 2020.

"You'd have to go all the way back to just before dawn on March 4, 1226, to see a closer alignment between these objects visible in the night sky," Rice University astronomer Patrick Hartigan said in a press release.

According to Hartigan's records, this year's Great Conjunction will have Jupiter and Saturn just one-tenth of one degree apart in the sky (that's 6.1 arcminutes, for the astronomers out there).

The positions of Jupiter and Saturn in the solar system relative to Earth, from Saturn Opposition on July 20, to the Great Conjunction on December 21, with the views from Earth. Credit: Celestia/Scott Sutherland

Technically, that makes this the closest Great Conjunction since July 16, 1623, when Jupiter and Saturn were only 5.2 arcminutes apart. However, as Hartigan points out, it would have been very difficult to see the 1623 event from Earth without some kind of special equipment. The two planets were too close to the Sun in our sky and thus were lost in the glare of twilight. Going back to March 4, 1226, Jupiter and Saturn were even closer than they come this year (just 2.1 arcminutes apart), and they were high enough above the horizon that anyone would have seen them with the unaided eye.

Now, in 2020, seeing this Great Conjunction for ourselves will require some planning. Jupiter and Saturn are nearly on the other side of the Sun from Earth on December 21. Thus, they will be very close to the horizon after sunset. So, while we will not need to find somewhere particularly dark to see this, we will need an excellent view of the horizon. This means a tall building or another high vantage point, or a wide-open field, with nothing obscuring the horizon.

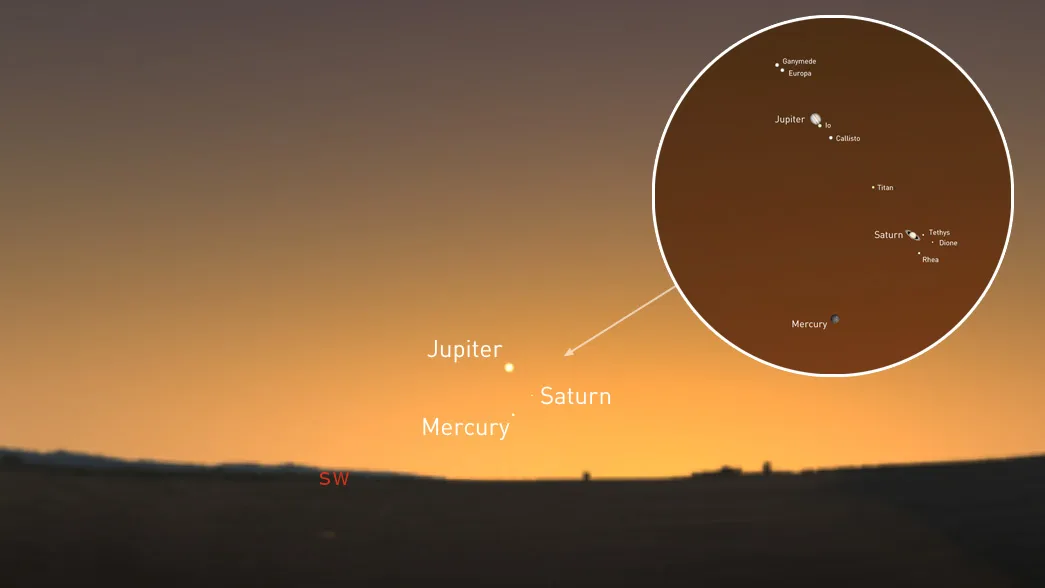

Jupiter and Saturn hover above the western horizon, just after sunset on December 21, 2020, during the Great Conjunction. Inset: both planets in a simulated telescopic view, along with several of their moons. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

It's definitely worth making plans to see this event if you can. We won't see another one like it for another 60 years.

One quick note: With these conjunctions happening every 19.6 years, one might ask: why don't we see Jupiter and Saturn overlapping every time? The answer lies in the 'inclination', or tilt, of the two planets' orbits. Jupiter's orbit is tilted by a little over 1.3 degrees compared to Earth's orbit, while Saturn's orbit is tilted by nearly 2.5 degrees. Those are small angles, but when you're talking about planets millions of kilometres away, it's enough to ensure that they only line up this well at specific times.

JANUARY 2 - EARTH AT PERIHELION

This event isn't so much something to see, but simply to experience...

Each year in early January, Earth reaches a point in its orbit known as perihelion — its closest distance to the Sun for the entire year.

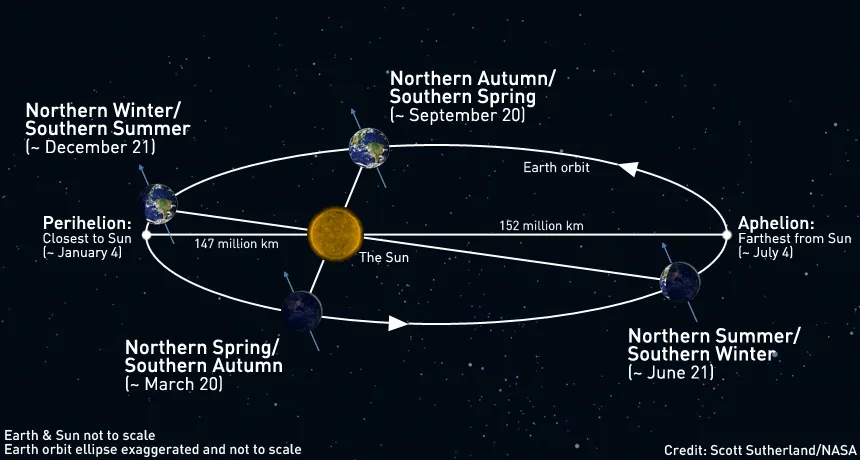

Earth's orbit around the Sun, noting the Solstices, Equinoxes and the timing of perihelion and aphelion. The image is not to scale. Credit: NASA/Scott Sutherland

If you want to mark the event, even if it's just to pause for a short break, it occurs at exactly 13:50 UTC, on January 2, 2021. That's:

10:20 a.m. January 2 NST

9:50 a.m. January 2 AST

8:50 a.m. January 2 EST

7:50 a.m. January 2 CST

6:50 a.m. January 2 MST

5:50 a.m. January 2 PST

At that exact time, Earth will be 147,093,163 km away from the Sun. That's a little farther away than we were at this same time last year, but closer than we'll be for at least the next few years ahead.

Will you feel anything when this occurs? Not specifically from the astronomical event, but it will still be pretty cool to mark the moment when it happens!

JANUARY 2-3 - QUADRANTID METEOR SHOWER PEAK

The best of the winter meteor showers occurs right after New Years' - the Quadrantids.

The location of the Quadrantid radiant, on the night of January 2-3, 2021. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

The Quadrantids originate from an asteroid known as 2003 EH1, which may be an 'extinct comet'. That makes it one of only two known meteor showers to originate from a rocky body! During this shower, the meteors are caused by tiny bits of debris from this asteroid as they plunge into the upper atmosphere and compress the air in their path.

According to the International Meteor Organization, this year's Quadrantids peak will occur on the night of January 2-3, specifically at 14:30 UTC, or around 9:30 a.m. EST. This favours viewers in western Canada, as the skies will still be reasonably dark close to the peak.

Usually, this wouldn't be an issue for anyone else, but unlike other meteor showers, the Quadrantids have a very sharp peak. The shower itself lasts for days — from December 28 to January 12 — but there's only a span of around 6 hours where the hourly rate of meteors spikes up into the double (and sometimes triple) digits.

The IMO says that, under dark skies, viewers can expect to see about 25 meteors per hour from the Quadrantids this year. Partly to blame for this is the timing of the Moon, which reached its Full phase on December 30. The light cast by the nearly 3rd quarter Moon will 'wash out' the dimmest meteors, leaving only the brightest for us to see.

Keep reading for our guide to watching meteor showers, below.

CONJUNCTIONS AND ALIGNMENTS

Look up into a clear sky on most nights of the year, and you'll likely spot the Moon, along with one or more planets. Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn are the most notable.

On certain nights of the year, these objects appear especially close together from our perspective here on Earth. Astronomers refer to these as conjunctions. As noted above, throughout 2020, Jupiter and Saturn were paired up in our sky nearly the entire year, culminating in a Great Conjunction on the Winter Solstice.

Here are the other notable conjunctions for Winter 2020-2021.

Jupiter, Saturn and Mercury form a tight triangle near the southwestern horizon, just after sunset on January 9, 2021. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

January 9 through 13 - Jupiter, Saturn and Mercury together, SW horizon after sunset

January 11 - Venus near very thin Crescent Moon, SE horizon just before dawn

February 18 - Mars near the 1st quarter Moon

March 5 - Mercury and Jupiter nearly overlap, SE horizon just before dawn

March 15 - Mercury, Jupiter, and Saturn form straight line, SE horizon just before dawn

March 19 - Mars near Waxing Crescent Moon

Mars tracks across the sky with the Waxing Crescent Moon on the night of March 19, 2021. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

MARCH 1 - THE ZODIACAL LIGHT

Moonlight and zodiacal light over La Silla. Credit: ESO

This winter, evening skywatchers will have a chance to see the immense cloud of interplanetary dust that encircles the Sun. This manifests in our night sky as a phenomenon known as The Zodiacal Light.

In the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada 2021 Observer's Handbook, Dr. Roy Bishop, Emeritus Professor of Physics from Acadia University, wrote: "The zodiacal light appears as a huge, softly radiant pyramid of white light with its base near the horizon and its axis centred on the zodiac (or better, the ecliptic). In its brightest parts, it exceeds the luminance of the central Milky Way."

According to Dr. Bishop, even though this phenomenon can be quite bright, it can easily be spoiled by moonlight, haze or light pollution. Also, since it is best viewed just after twilight, the inexperienced sometimes confuse it for twilight and miss out.

On clear nights, and under dark skies, look to the western horizon, in the half an hour just after twilight has faded, from about March 1 to March 14.

MARCH 20 - EQUINOX

As our Earth travels in its orbit, the tilt of the planet causes the angle of the Sun to change in our sky.

From late September to late March, the North Pole is angled away from the Sun so that the Sun is positioned more directly over the southern hemisphere. The Sun reaches its lowest point in the northern sky (and highest in the southern sky) on or around December 22.

From late March to late September, conversely, the South Pole is angled away from the Sun. The Sun is positioned more directly over the northern hemisphere, reaching its highest point in the northern sky (and lowest in the southern sky) on or around June 22.

At two points between these periods — specifically around March 20 and September 22 — it appears to us as though the Sun crosses the equator. In March, it traverses from south to north, and in September, it travels from north to south. The exact moment the Sun is over the equator, in either case, is known as an Equinox.

The coming Equinox, marking the start of Spring in the north and autumn in the south, occurs at exactly 5:37 a.m. EDT, on March 20.

TIPS FOR METEOR WATCHING

First, some honest truth: Many people who want to watch a meteor shower end up missing out on the experience. Follow this guide to get the most out of these events.

Here are the three 'best practices' for watching meteor showers:

Check the weather,

Get away from light pollution, and

Be patient.

Clear skies are very important for meteor-spotting. Even a few hours of cloudy skies can ruin an attempt to see a meteor shower. So, be sure to check The Weather Network on TV, on our website, or from our app, and look for my articles on our Space News page, just to be sure that you have the most up-to-date sky forecast.

Next, you need to get away from city light pollution. If you look up into the sky, are the only bright lights you see street lights or signs, the Moon, maybe a planet or two, and passing airliners? If so, your sky is just not dark enough for you to see any meteors. You might catch a bright fireball, but there's no guarantee, and those are typically few and far between. So, get out of the city, and the farther away you can get, the better!

Watch: What light pollution is doing to city views of the Milky Way

For most regions of Canada, getting out from under light pollution is simply a matter of driving outside of your city, town or village until a multitude of stars is visible above your head. In some areas, especially southwestern and central Ontario and along the St. Lawrence River, the concentration of light pollution is too high. Getting far enough outside of one city to escape its light pollution tends to put you under the light pollution dome of the next city over.

In these areas of concentrated light pollution, there are dark sky preserves. However, a skywatcher's best bet for dark skies is usually to drive north and seek out the various Ontario provincial parks or Quebec provincial parks. Even if you're confined to the parking lot after hours, these are usually excellent locations from which to watch (and you don't run the risk of trespassing on someone's property).

Sometimes, based on the timing, the Moon is also a source of light pollution, and it can wash out all but the brightest meteors. We can't get away from the Moon, so we can just make do as best we can in these situations.

Once you've verified you have clear skies and you've gotten away from light pollution, this is where having patience comes in.

For best viewing, you must give your eyes time to adapt to the dark. Give yourself at least 20 minutes, but the longer, the better. Warning: if you skip this step — even if you follow the rest of this guide — you will miss out on a lot of the action.

During this adjustment time, avoid all bright light sources - overhead lights, car headlights and interior lights, and cellphone and tablet screens. Any exposure to bright light during this period will cancel out some or all the progress you've made, forcing you to start over. Shield your eyes from light sources. If you need to use your cellphone during this time, set the display to reduce the amount of blue light it gives off, and reduce the screen's brightness as much as possible. It may also be worth finding an app that puts your phone into 'night mode' to shift the screen colours into the red end of the light spectrum, which has less of an impact on your night vision.

You can certainly look up into the starry sky while you are letting your eyes adjust. You may even see a few brighter meteors as your eyes become accustomed to the dark. If the Moon is shining brightly, turn so that it is out of your personal field of view.

Once you're all set, just look straight up!