Meteorological winter begins today! Why? It's all about the science!

Wait! Doesn't winter begin on December 21 in 2025? It sure does, but this winter is for science!

Did you know that there are actually two different sets of seasons, and thus two different winters, every year? Astronomically, the First Day of Winter occurs at the Solstice, around the 21st of December. However, meteorologically, the season begins three weeks earlier, on the 1st of December. This is the story behind Meteorological Winter.

Throughout the year, we typically use four different dates on the calendar to mark the passage of the seasons, each keyed to the Sun's journey across our skies.

Here, in the northern hemisphere, the December Solstice corresponds to when the Sun reaches its lowest point in the sky. Following that, the March Equinox is when it appears directly above the equator, as it heads from south to north. Then, on the June Solstice, the Sun reaches its highest point in the sky, and on the September Equinox, it appears above the equator again, this time going from north to south. Meanwhile, in the southern hemisphere, this is all flipped on its head, with the December Solstice marking when the Sun is highest in the sky, and so on.

These dates, and the seasons that lie between them, have been observed for centuries.

The reason for the seasons, and the source of this apparent motion of the Sun as it crosses our sky, is the tilt of Earth's rotational axis.

As our planet orbits the Sun, it traces out a flat, nearly perfect circle that we call the Ecliptic. However, the ecliptic doesn't line up with Earth's equator. Instead, probably due to the fact that it was struck by a Mars-sized protoplanet early in its formation, the axis the planet rotates around is tilted, by approximately 23.4 degrees.

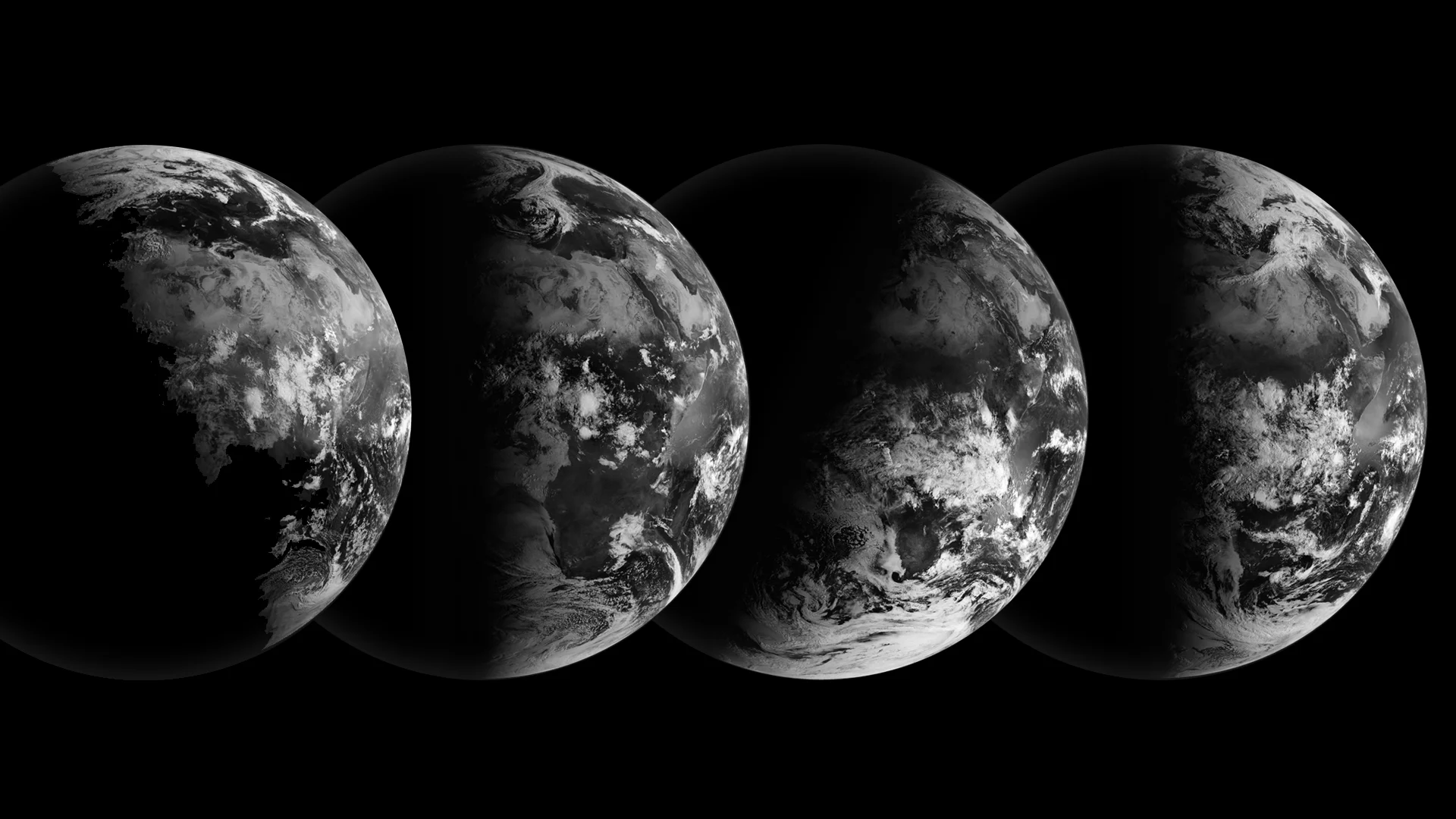

These satellite views of Earth show the start of the four seasons. From left to right, with respect to the northern hemisphere, we see the summer solstice, fall equinox, winter soltice, and spring equinox. Credit: NASA

So, during each of our year-long journeys around that orbit, Earth's tilt causes our perspective on the Sun to change.

For half of the year, it climbs higher in our sky each day, until it reaches its highest point. For the rest of the year it gets lower in the sky, until it reaches its lowest point. Then, the pattern starts all over again.

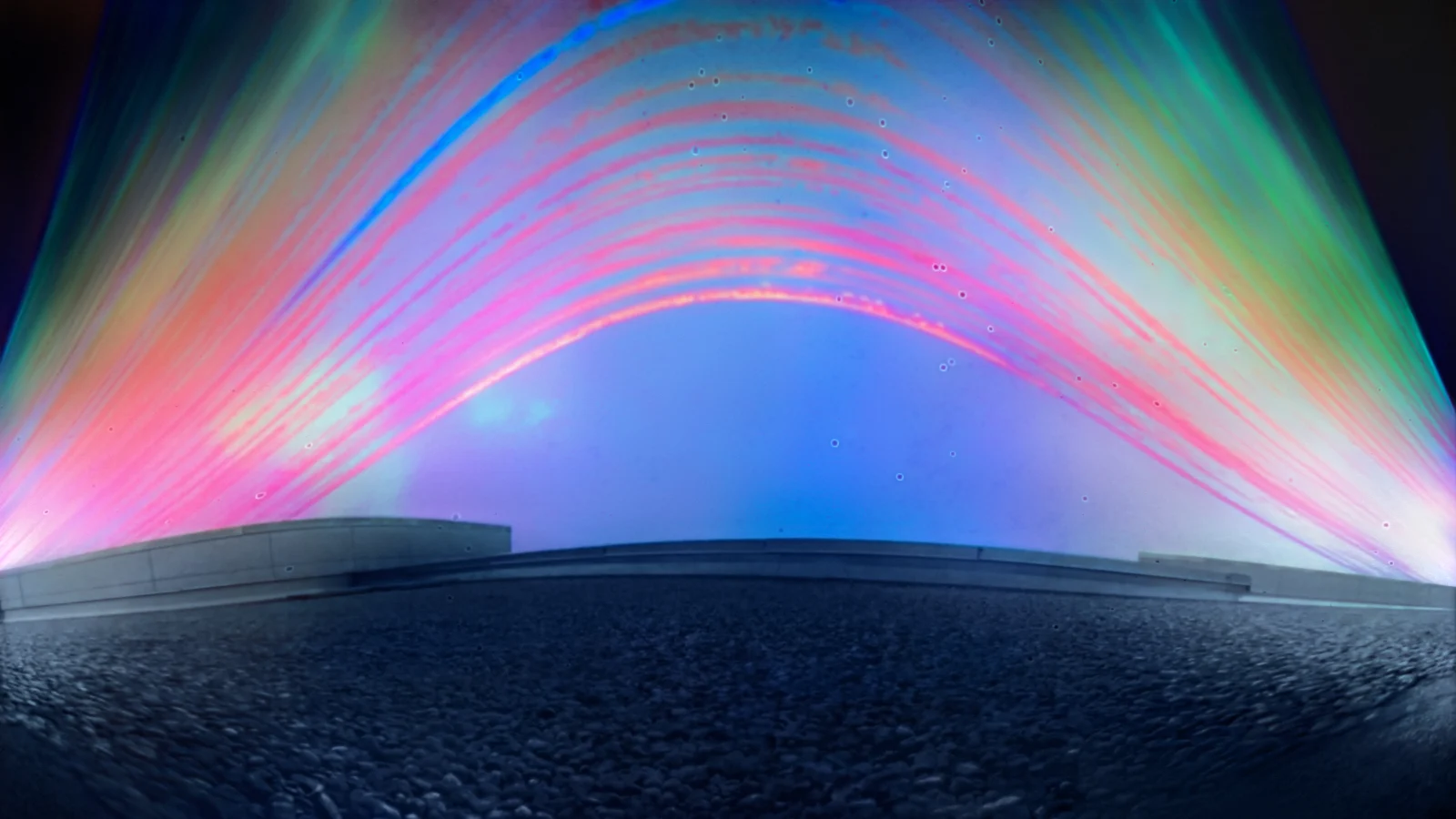

This 'solargraph' image captures the Sun's path across the sky, day by day, between June 21 and December 21, 2023, from atop Weather Network Headquarters. Credit: Bret Culp

READ MORE: What is a solargraph? How to record the Sun's seasonal journey across our sky, all in one image

Using this astronomical timing to define our seasons works just fine, in general.

However, specifically when it comes to keeping track of our weather and climate, they don't work quite as well. The start and end dates of the astronomical seasons typically fail to capture the weather that most defines a particular season. Also, they definitely do not mesh well with how we keep records of weather conditions throughout the year.

Shifting alignment

When keeping weather and climate records, consistency is essential.

Daily, weekly, monthly, and even yearly records satisfy this requirement quite well. A day is always 24 hours, a week is always 7 days, and except for the occasional leap year, each month is always the same length and each year is always 365 days. This helps atmospheric scientists to easily make comparisons, find extremes, and track trends in their recorded weather.

Comparing seasonal trends is important too. However, astronomical seasons aren't great for that purpose, as they are anything but consistent. Due to the influence of the Moon and the other planets, slight changes are introduced into the timing of Earth's orbit and rotation. As a result, exactly when the equinoxes and solstices occur also changes, which throws an added complication into the process.

Without meteorological seasons for comparison, the 'above normal', 'normal', and 'below normal' regions of this map would be much more difficult to predict. (The Weather Network)

It's not that comparisons can't be made. These days, computers can easily tally all the weather records between the precise start and end times for any astronomical season. However, comparing the resulting tallies to each other would then require a whole host of adjustments and corrections to account for the differences in length.

That's just the modern complication, though. The first meteorological network was established way back in 1780, by Societas Meteorologica Palatina. At that time, all record-keeping and calculations were done by hand, and this continued to be the case until computers were invented in the latter half of the 20th century.

So, for the first 300 years of weather records, making seasonal comparisons and calculating seasonal trends would have been far more cumbersome using astronomical seasons.

To better align the seasons with how weather records were kept, meteorological seasons were created.

Each is still three months long, but unlike astronomical seasons, they align precisely with our calendar months. Therefore, they start and end on the exact same dates every year.

Meteorological spring begins on the 1st of March, meteorological summer starts on the 1st of June, meteorological fall begins on the 1st of September, and meteorological winter starts on the 1st of December.

Does it make that much difference?

Meteorological seasons do more than bring consistency to seasonal comparisons. They also tend to capture the most 'representative' weather of each season.

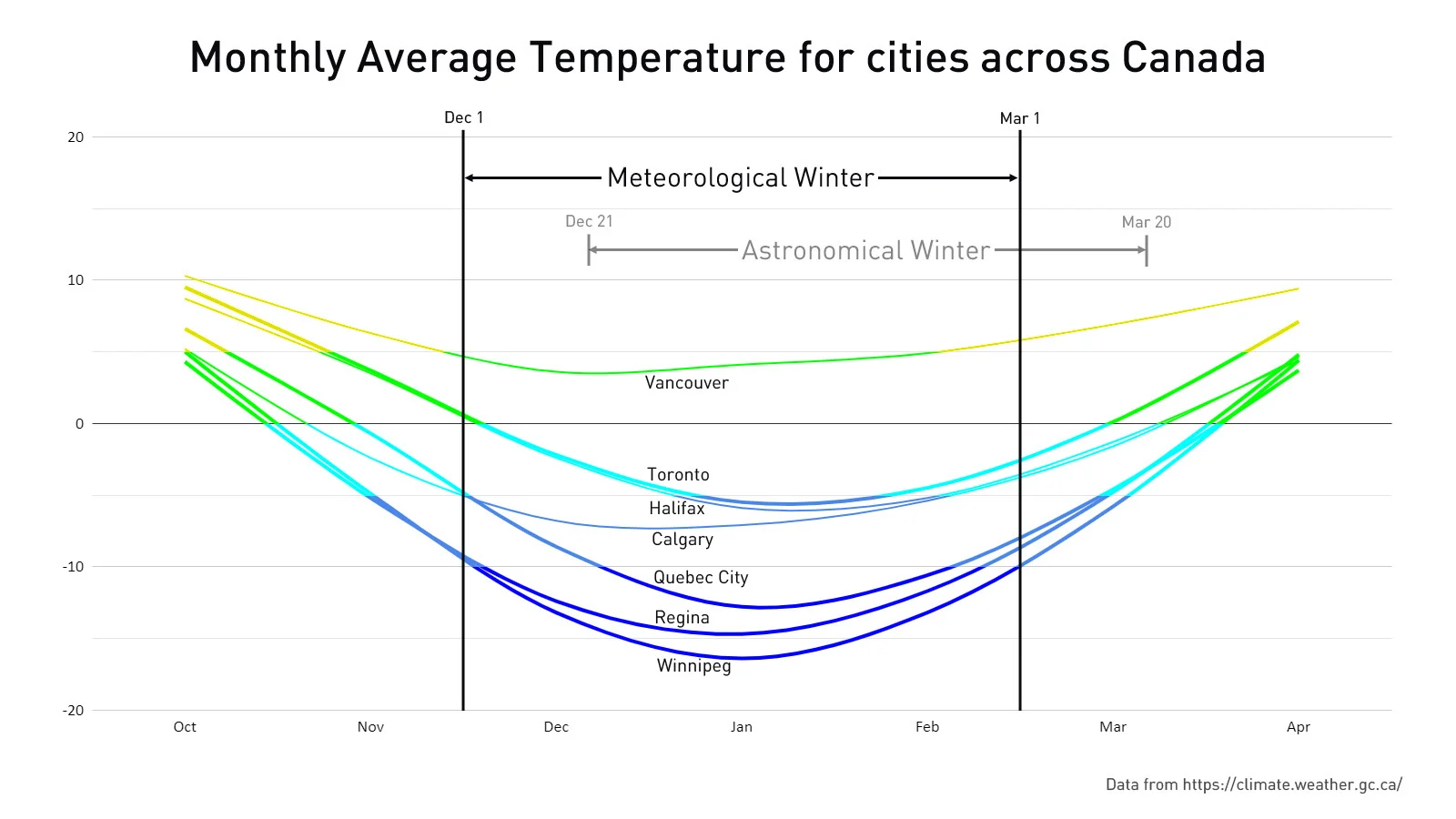

This graph plots average daily temperatures between October and April for seven cities across Canada. The start and end dates for both astronomical and meteorological winter are also indicated, to compare how they align with these temperatures. (Data from Environment and Climate Change Canada)

While some Canadian cities experience much colder winters than others, as the graph above shows, nearly all follow a similar temperature trend throughout the season.

What's clear here is that, over the long term, the coldest part of that trend is captured far better by meteorological winter than its astronomical counterpart.

(Thumbnail image courtesy of Kalyna Steciw, who took this picture from Edmonton on December 31, 2021, and uploaded it to The Weather Network's UGC gallery)