What to do if you get caught in a rip current

It might surprise those of us who cottage on the Great Lakes to know that rip currents are much more common—and deadly—than most of us realize. “It’s very much an overlooked issue,” says Chris Houser, a professor in the School of the Environment at the University of Windsor. That is, until the widely publicized story from early August about a Toronto-area family of four, caught in a rip current off a beach in Grand Bend, Ont., and rescued by an off-duty firefighter who was there with his own family.

Houser says that the conservative estimate is that approximately 30 per cent of drowning fatalities are associated with rip currents.

A rip current (riptide is a misnomer) can occur in any body of water in which there are breaking waves says the Lake Huron Centre for Coastal Conservation. They are narrow, fast-moving currents that run perpendicular to the beach. Rip currents differ from an undertow, says Houser: “Where the undertow flows at your feet, rip currents flow at the top of the water at chest level, where you are most buoyant.” Rip currents don’t pull us under, they pull us out to where we can’t touch the bottom. Because they’re hitting us at chest level, says Houser, we can’t get on top of them, as we typically can with undertows.

You’re most likely to find rip currents near low spots in sandbars or close to jetties or groynes (the Grand Bend incident took place near a pier).

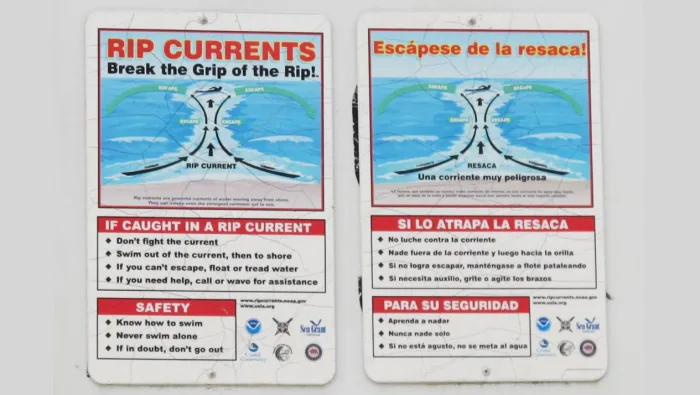

Houser urges three steps to survive a rip current:

The most effective step is prevention. Steer clear of beaches without lifeguards.

Don’t trust the behaviour of other people. If there are big waves, there are likely going to be rip currents. Just because other people are swimming, doesn’t mean it’s safe. If you do get caught in a rip current, the best thing you can do—and perhaps the hardest—is remain calm. “Get your feet up,” says Houser, which means your mouth won’t be at water level, and you’re less likely to swallow water.

Don’t fight the current, it’s too strong. Instead, try and swim parallel to shore. Remember a rip current is narrow—if you can get yourself out of its path, the waves will then help push you toward shore. If you’re too tired, float on your back. The current will continue to take you out, which is scary, but once you’re on the far side of the sandbar, the water will be calmer, and you can swim back to shore, avoiding the current.

Thumbnail image courtesy: Invertzoo/Wikipedia CC BY SA 4.0