What lives in the Pacific's 'ocean desert'

On Earth, the farthest place from land is a spot in the heat of the South Pacific Gyre. What lives there? This is what we know.

Do you know where to find Nemo? In the heart of the South Pacific Gyre; the area of water that is furthest from land. It's called Point Nemo because the name means "no-one." It's an apropos name because just like a land desert, not much lives there. Or so we thought (cue dramatic scene-transition music).

The South Pacific Gyre (SPG) accounts for 10 per cent of the world's ocean surface. The area covers about 37 million square kilometres and is the largest of Earth's five giant ocean-spanning current systems. Point Nemo stretches 17 million square kilometres. So, we're talking about a pretty significant chunk of our world. But due to its remote location, studying the area is extremely difficult.

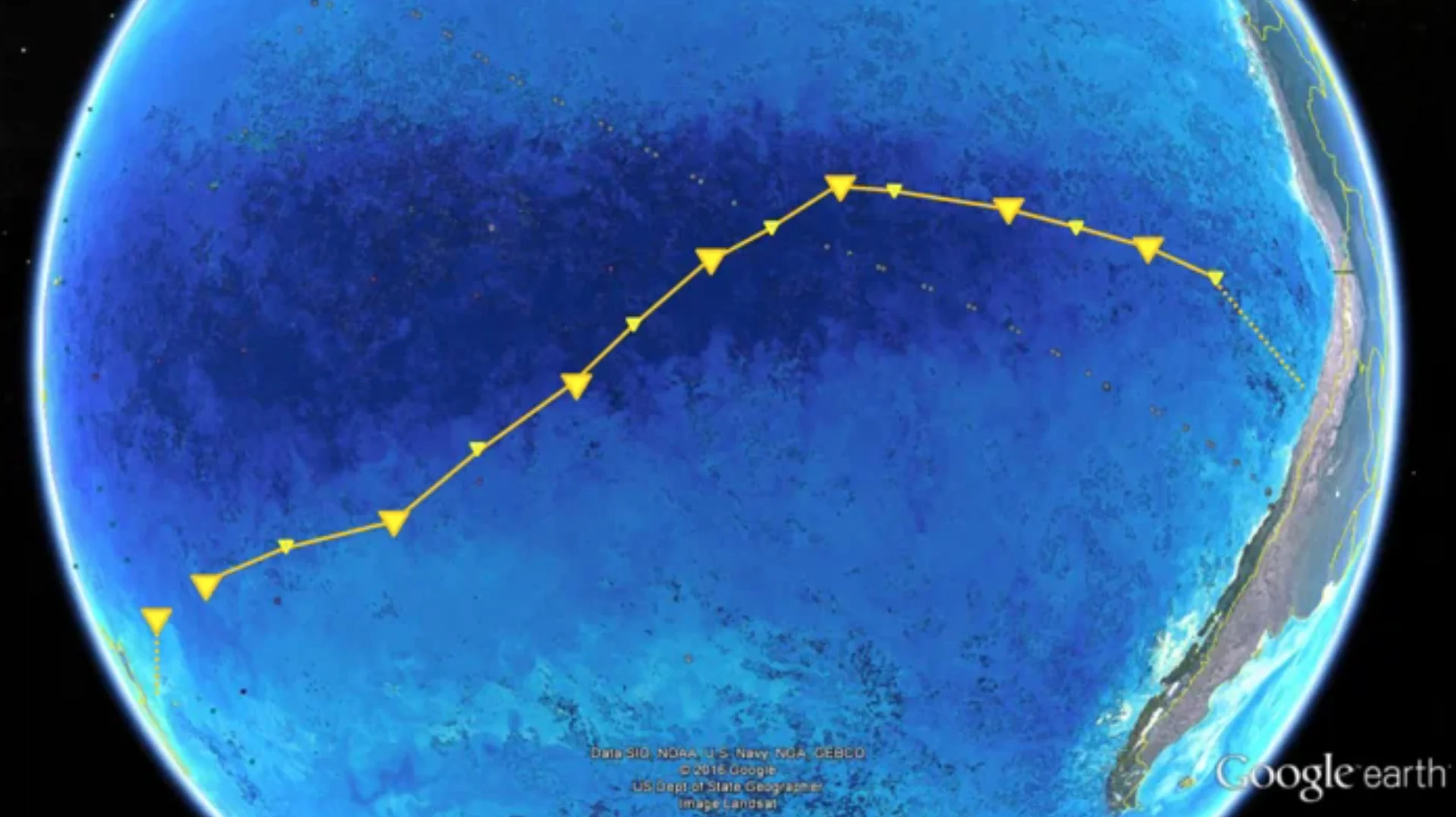

One 6-week study, spanning from December 2015 to January 2016, collected microbial samples from across the SPG. The crew, led by Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, sailed 7,000 kilometres from Chile to New Zealand. They collected samples from depths ranging from 65 to 16,400 feet. This is what they found:

Firstly, when comparing the South Pacific surface waters to ocean gyres in the Atlantic, they only found two-thirds of the microbial cells. Microbial ecologist, Bernhard Fuchs, said "It was probably the lowest cell numbers ever measured in oceanic surface waters."

Secondly, even though the area is geographically unique, the microbes that were found are the same found in other gyre systems. They found 20 major bacterial clades, such as, SAR11, SAR116, SAR86, and Prochlorococcus. None of which sound like a cute little-finned clownfish.

Lastly, and perhaps most significantly, one of the microbe populations collected, called AEGEAN–169, was a lot denser at the SPG's surface waters, compared to the usual 500-meter depth where scientists have previously located them.

The density of these populations are affected by the depth of the water, changes in temperature, nutrient concentration, and light availability.

So what lives in the South Pacific desert? Not much. It's a pretty "ultraoligotrophic" area, meaning sparse in nutrients. But microbiologist Greta Reintjes help explains the AEGEAN–169 phenom, saying it "indicates an interesting potential adaptation to ultraoligotrophic waters and high solar irradiance."

Reintjes adds that the discovery "is definitely something we will investigate further." Aka, just keep swimming.