'Living buildings' made of fungi? Could they help us adapt to climate change?

A team of Vancouver academics is fusing the fields of microbiology and architecture to create living building materials made out of oyster mushrooms and other edible fungi.

They say their research into "engineered living materials" could help curb the construction industry's high energy and environmental impact, replace traditional insulation, or even help regulate indoor temperatures as the climate warms.

DON'T MISS: Living in an Earthship, this Ontario couple inspired others to build their own

One day it could even potentially help filter air pollutants such as wildfire smoke, according to a postdoctoral fellow at the University of B.C.

"This idea of engineered living materials, it's a very new concept," said Nicholas Lin, an engineer with expertise in microbiology.

"These materials are assembled by combining raw materials with living cells and exhibit some certain properties of living systems," explained Lin, whose research straddles both UBC's microbiology and architecture schools.

His teammates at UBC's Biogenic Architecture Lab are creating various building materials filled with mycelium — the fuzzy-looking network of tiny, pale underground strands, or hyphae, that serve a function similar to plants' roots.

But fungi, one of the oldest organisms on the planet at more than a billion years old, are neither plant nor animal.

The team of researchers mainly work with edible species, such as oyster, reishi and turkey tail mushrooms.

A 3D printer at the University of B.C. creates layers of a hydrogel solution that is infused with reishi mushroom mycelium, a network of thin strands known as hyphae that are equivalent to fungi's roots. (Submitted by UBC Biogenic Architecture Lab)

"Oyster is probably the most popular one because we know it's edible, there's no known toxicity and it grows very fast," Lin said.

'Dynamic, tunable'

One of his supervisors is associate architecture professor Joseph Dahmen.

Dahmen said his main inspiration over his years researching what he calls "mycelium biocomposites" was to reduce the energy and environmental impact of construction materials.

"The lion's share of the energy going into buildings is in the materials themselves," he told CBC News. "Mycelium biocomposites offer a kind of biodegradable material to replace those."

To make the engineered living materials — whether bricks, gels that can take any shape, insulation, or drywall-like boards — he said the researchers mix mushroom spores with something high in cellulose, often a recycled or byproduct material such as sawdust, wheat chaff or rice husks.

(Nathan Coleman/The Weather Network)

While this has been done for years around the world with both fungi and bacteria, he explained, often the finished product is "cooked" to kill the organisms.

"We didn't invent the process," he said. "But what we're really interested in is the potential of these materials if they remain alive.

"So you could imagine a material that then becomes dynamic, tunable. We can make it different strengths. It goes on growing."

'Grows like mushrooms'

While Lin's PhD research had him killing microorganisms by creating antibacterial surfaces, now he's using 3D printers to help create a gel full of them.

"It's kind of similar actually, to kill something and to raise it," he mused. "Some parts of it are are quite similar in the way you maintain a pure culture.

"But one thing that's always really interesting is — if you if we neglect the fungi, or if we forget to check up on it — sometimes it'll fruit a little oyster mushroom."

Oyster mushrooms grow out of bricks molded from mycelium. They were used to build a wall for an art installation created by AFJD, the design studio of Joe Dahmen and his wife Amber Frid-Jiminez. (AFJD)

The speed oyster and other fungi can spread allows the researchers to test new ideas quickly.

And that's led the UBC lab to develop everything from a mushroom-based composting toilet to solid sawdust bricks and benches.

"The expression 'grows like mushrooms' is actually accurate," Dahmen joked. "They're very fast growing, and they tend to be hydrophobic so they can repel water.

"We can match them to the unique environmental considerations for where we want to employ them."

Dahmen said at present a whole house made of 3-D printed living mushrooms is purely hypothetical.

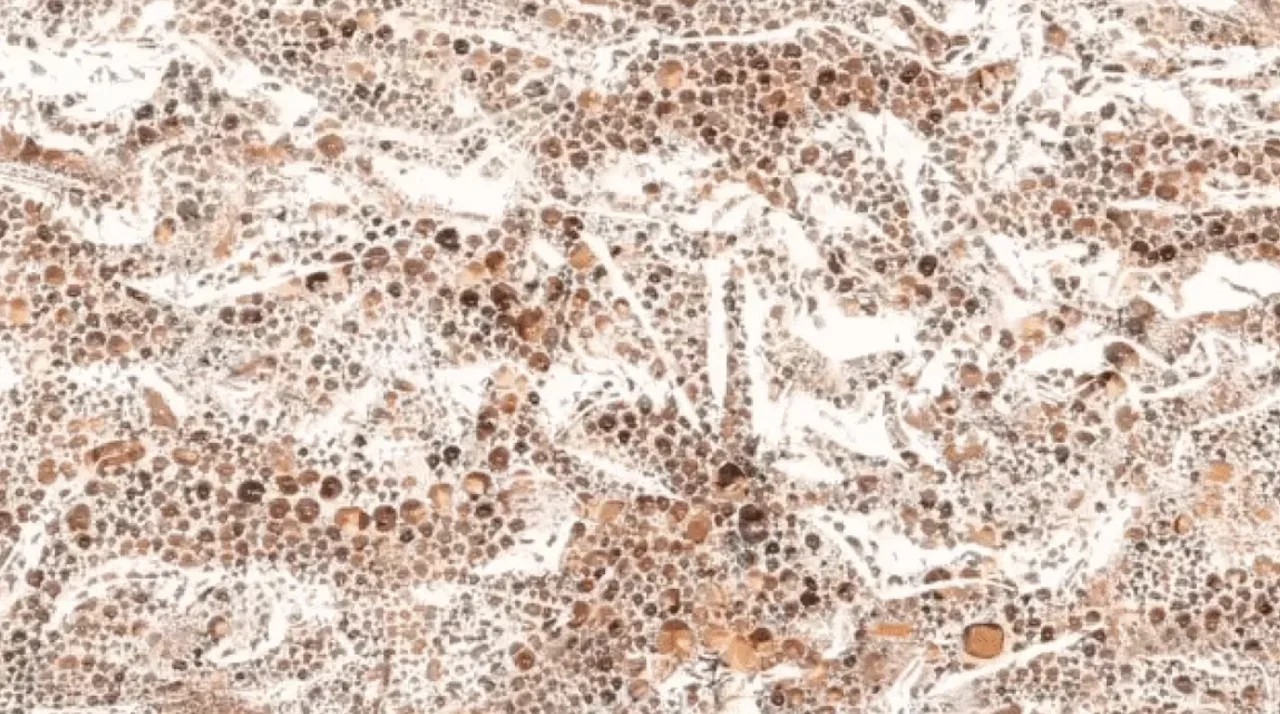

A microscope image shows how mycelium, the equivalent of roots for mushrooms, spread or inoculate a growth bag in a University of B.C. laboratory. (Submitted by UBC Biogenic Architecture Lab)

"I would say we're probably still a few years away from incorporation in mainstream buildings," he said. "But we're just starting to understand some of the potentials of these materials."

Built-in climate control

Lin said there are some even more complex functions the future may hold for living building materials — based on what he called the "environmental responsiveness" of fungi's hyphae.

A study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences this year found mushrooms could lower their temperature by an average of 3 C below their surroundings — which, Lin said, could point to climate control applications as the climate warms.

And with climate change worsening Canada's wildfire seasons, living materials filled with fungi might one day help clean the air in our homes.

An architectural artist rendering of a hypothetical home built using 3D-printed biocomposite materials filled with microscopic networks of fungi mycelium. (Submitted by UBC Biogenic Architecture Lab)

"Could we engineer these mushrooms so if there's a lot of smoke from wildfires, they could recognize that — and produce more of these fibrous fuzzy materials to capture this particulate matter?" he speculated.

That's an idea that's still mostly science fiction, but Lin believes it requires further research.

"In the very, very far future, these biological tools might give us new ways and new insights to produce materials that are faster, better, cheaper — and in the long term, more ecologically sound," he said.

WATCH: This B.C. family lives off the land, and off the grid in Freedom Cove

Thumbnail courtesy of UBC Biogenic Architecture Lab via CBC.

The story was originally written by David P. Ball and published for CBC News.