Scientists warn Earth warming faster than expected — due to ship pollution drop

The past five months have shattered global temperature records, taking scientists by surprise. Many are asking why.

A new study published in Oxford Open Climate Change, led by renowned U.S. climate scientist James Hansen, suggests one of the main drivers has been an unintentional global geoengineering experiment: the reduction of ship tracks.

SEE ALSO: Canada's 'Climate Barbie': How Catherine McKenna moved from insult to owning it

As commercial ships move across the ocean, they emit exhaust that includes sulfur. This can contribute to the formation of marine clouds through aerosols — also known as ship tracks — which radiate heat back out into space.

However, in 2020, as part of an effort to curb the harmful aerosol pollution released by these ships, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) imposed strict regulations on shipping, reducing sulfur content in fuel from 3.5 per cent to 0.5 per cent.

The reduction in marine clouds has allowed more heat to be absorbed into the oceans, accelerating an energy imbalance, where more heat is being trapped than being released.

In a call with reporters on Thursday, Hansen said Earth's energy imbalance is much higher than a decade ago.

"That imbalance has now doubled. That's why global warming will accelerate. That's why global melting will accelerate," he said.

When asked if this was evidence of the extreme warming we've seen over the past five months, Hansen replied, "Yeah. Absolutely it is."

WATCH: NASA illustrates the 2023 ozone hole over Antarctica

1.5 C limit 'deader than a doornail'

Hansen said the IMO regulations, which were designed to reduce aerosol pollution, will have a long-term warming effect on the climate, pushing global temperatures 1.5 C above pre-industrial levels and potentially even 2 C — the threshold governments said they would try to stay within under the Paris Accord — even faster.

"The 1.5-degree limit is deader than a doornail," said Hansen, whose 1988 congressional testimony on climate change helped sound the alarm of global warming. "And the two-degree limit can be rescued, only with the help of purposeful actions."

Before the reduction of sulfur in ships, the only way to calculate the effects were through modelling, Leon Simons, a climate scientist and co-author of the recent study, told CBC News, which is likely why scientists didn't see the rapid warming coming.

But since the reduction of sulfur in shipping, we're seeing the effects play out in real time.

"We've never done the experiment of reducing emissions over the oceans by 80 per cent before," Simons said. "So now we are starting to have the evidence. We now have about three and a half years of evidence of what happens … to the oceans if you reduce sulfur emissions from shipping by 80 per cent."

But not everyone agrees.

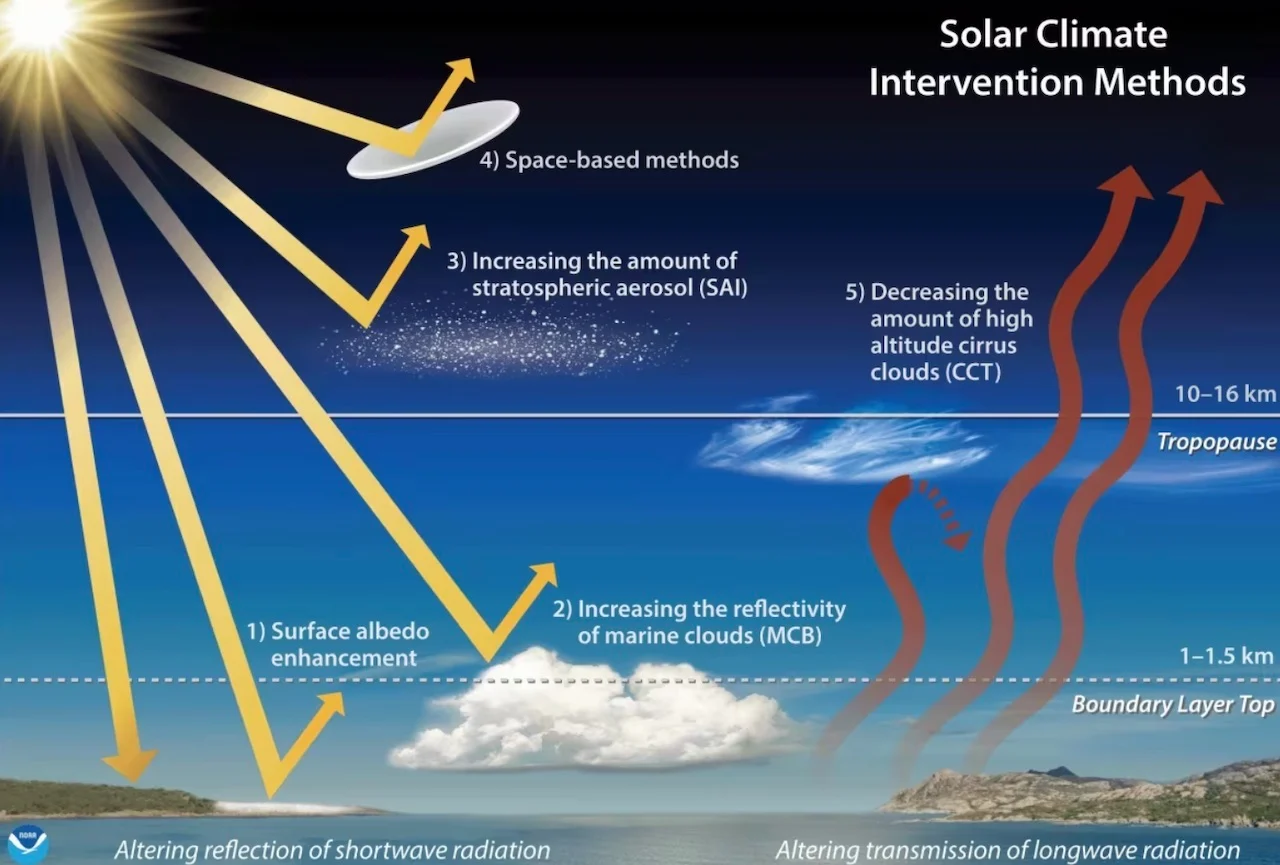

This image illustrates different forms of solar radiation management, a form of geoengineering. (Wikimedia Commons/NOAA)

U.S. climatologist Michael Mann wrote a blog about the paper's findings, saying, "[Hansen] and his co-authors are very much out of the mainstream with their newly published paper in the journal Oxford Open Climate Change. That's fine, healthy skepticism is a valuable thing in science. But the standard is high when you're challenging the prevailing scientific understanding, and I don't think they've met that standard, by a longshot."

Simons noted that Mann "hasn't studied this at all."

"He doesn't address the the most important scientific data, which is NASA satellite data," Simons said.

'Long-term warming effect'

Michael Diamond, an assistant professor at Florida State University's department of earth, ocean and atmospheric science who was not involved with the study, said he agrees that the IMO regulations "will have a long-term warming effect on Earth's climate, as will other reductions in air pollution, like the big air quality improvements we've seen over China since 2013."

In an email to CBC News, Diamond said that he agrees aerosol cooling has masked roughly one-third of warming from greenhouse gases.

"However, it's important to emphasize that we are not doomed to experience all of that 'masked' warming as we clean up air pollution, if we also reduce concentrations of shorter-lived greenhouse gases like methane at the same time."

The paper's authors suggest that there are only three ways to try to halt this rapid warming:

A global increasing price on greenhouse gas emissions, which would include carbon taxes.

Co-operation between eastern and Western countries "in a way that accommodates developing world needs."

Efforts to reduce Earth's radiation imbalance, which could include some form of geoengineering.

WATCH: Cruise ship ban will spare B.C. coast from extra pollution

Geoengineering efforts could include solar radiation management — such as spraying salty droplets into the air from sailboats — which could bounce the sun's rays back into space, which would in turn cause cooling.

But the authors noted vigorous research is needed to ensure there are no unintended consequences.

"There are ways to do it, and not just putting aerosols in the stratosphere," Hansen said. "Rather than describe those efforts as 'threatening' geoengineering, we have to recognize we're geoengineering the planet right now."

The paper's authors also noted that there is a need for more research, including satellite observations, and a need to communicate the potential consequences of such a massive energy imbalance and what policies should be put in place to mitigate the threat to people around the world.

"Even if there is uncertainty … that is a reason to take [the effect of fewer ship tracks] even more seriously," Simons said. "Because if there is uncertainty, we might also be underestimating what's happening."

Thumbnail courtesy of MODIS/NASA via CBC.

The story was written by Nicole Mortillaro and published for CBC News.