More birds are getting whipped around in stronger hurricanes, study finds

Large volumes of birds have been detected in hurricanes that are increasingly severe, radar data reveals.

For hundreds of years, people have witnessed birds being drawn into hurricanes and historical records dating back to the 1800s include observations from sailors that noticed the exhausted animals landing on the bow of the ship while travelling through the hurricane’s eye. Now that hurricanes are becoming stronger and more frequent, how are the birds being affected?

Matthew Van Den Broeke, an associate professor of earth and atmospheric sciences at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, explored the answer to this question in his latest study published in Remote Sensing in Ecology and Conservation.

Dual-polarimetric radars are used by forecasters to predict the weather, such as the volume and timing of incoming rain. These radars can also pick up on other animate objects such as bioscatter, which are organisms including insects and birds.

Van Den Broeke analyzed the dual-polarimetric radar data from 33 Atlantic hurricanes that struck the U.S. coast or Puerto Rico from 2011 to 2020 and noticed bioscatter in various parts of a hurricane, such as in the eye and outer rainbands. Bioscatter was found in every single hurricane, but Van Den Broeke says that the amount of bioscatter significantly differed based on the type of storm.

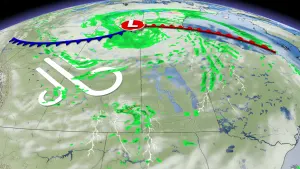

A radar image that shows Hurricane Michael making landfall in Florida as a destructive Category 5 storm on October 10, 2018. The blue cluster indicates bioscatter, birds in this case, and the small black dot above the blue cluster is the radar dish. (Matthew Van Den Broeke/ University of Nebraska-Lincoln)

“It seemed like these more intense hurricanes that had a really well-defined eye often had bigger, taller, more dense signatures which would indicate more birds in there,” Van Den Broeke said to The Weather Network.

Hurricane Harvey, which made landfall on Texas and Louisiana in August 2017 as a Category 4 storm, was cited by Van Den Broeke as an example of a particularly notable hurricane he analyzed. Harvey set the record for the wettest tropical cyclone ever recorded in the U.S., a trend that many climate scientists link to human-induced climate change.

Hurricane intensity was the variable that was most strongly associated with bioscatter, which the study says could be because birds are there when the storm forms or because it is unlikely they will try flying through the winds and thunderstorms that surround the hurricane’s eye.

It is dangerous for a bird to attempt to leave a hurricane with high wind speeds and Van Den Broeke stated that this causes birds to stay in severe hurricanes for significant lengths of time, which can be a week in the air and travelling thousands of miles. In fact, the study says that the researchers “speculate that a mature hurricane could transport a bird for as long as the hurricane is over water.”

Homes flooded after Hurricane Harvey (2017) in Texas. (michelmond/ iStock/ Getty Images Plus)

The study reported that the largest amounts of bioscatter appeared in hurricanes from July to October when many avian species are migrating south for the winter. On average, bioscatter was also larger and denser in hurricanes that made landfall on the Gulf Coast and in Florida, likely due to higher avian biodiversity and concentration of birds.

Van Den Broeke says that increasingly frequent and strengthening hurricanes could have impacts on bird diversity and avian ecosystems. “Population dynamics could hypothetically be skewed, or invasive species introduced, by a hurricane of the right intensity crossing a migratory route at the wrong time,” Van Den Broeke stated in the university’s press release.

There is still much to learn about how birds are transported by hurricanes. The study’s data analysis revealed that the cruising altitude of trapped birds also increases with hurricane intensity, but it is not clear why. Van Den Broeke suspects it could be because of hot, moist air near the ocean’s surface that rises in the eye until it reaches a boundary beyond which drier air from above is sinking.

Given the curiosities about how birds spend their time during the hurricane’s eye and how these twisters are changing as the climate warms, Van Den Broeke says that bioscatter data could be used to provide more details to forecasters and meteorologists that are studying hurricanes.

Thumbnail credit: piola666/ iStock/ Getty Images Plus