Five ways climate change will impact the booze we drink

The short answer: Less booze, pricier booze, and worse booze.

The effects of climate change are so all-encompassing, it can be hard to keep track of them all, but every now and then you'll hear of one that jolts your attention back to it.

For people who like a drink from time to time, here's that jolt: Climate change is set to do a real number on alcohol, from your favourite suds through to tequila. Here's five examples.

BEER

Here’s one that’ll hit a lot of people really hard: Beer, the world’s most popular alcoholic beverage, is set to be harder to come by, and thus, more expensive.

There’ve been a few studies over the years that have suggested climate change will do a number on your suds, the latest one from October 2018, when scientists at the University of East Anglia modelled what would happen to global barley yields in a world with more extreme heat and drought events.

They found the drop in the world’s barley supply ranged from three to 17 per cent. That doesn’t sound like much, until you remember beer isn’t the only thing barley is used for, and most countries won’t put booze at the top of their food security priority list. It also wouldn’t be evenly spread, ranging from an 83 per cent decline in Brazil to just nine per cent in Australia.

That means beer production will drop. But by how much? The researchers say, during the most severe events, the decline will be around 16 per cent, or 29 billion litres, with prices more or less doubling. Even in the mildest cases, consumption falls by four per cent but prices still jump by 15 per cent.

In terms of sheer volume of suds, some of the declines are staggering. China sees the biggest decline, a drop of around 4.3 billion litres (that’s with a “b”). Canada’s population may be tiny by comparison, but should still see a fall of 630 million litres, and about a doubling of prices.

And that’s literally not accounting for taste. When drought hit the U.S. West Coast in 2015, the country’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration took a look at the effect it had on hops production in Washington, where 73 per cent of the nation’s supply grows.

Hops are the key source of beer’s flavour, and the researchers found some varieties did poorly, but overall, the harvest was the largest in a century. It seems producers supplemented their usual water sources by drawing on more groundwater, which worked fine for 2015, but will become less sustainable as extreme drought events become more common.

Even so, there’s another kind of trouble brewing. Relying on groundwater rather than river water for production has an effect on taste, given the higher level of minerals, with one producer describing it like “brewing with Alka-Seltzer.”

So: Less beer, pricier beer, and potentially worse beer. It’s not looking good for beer lovers.

RELATED: WHICH WEATHER IMPACTS BEER SALES THE MOST?

WINE

For lovers of the vine, a warmer world will be a double-edged sword.

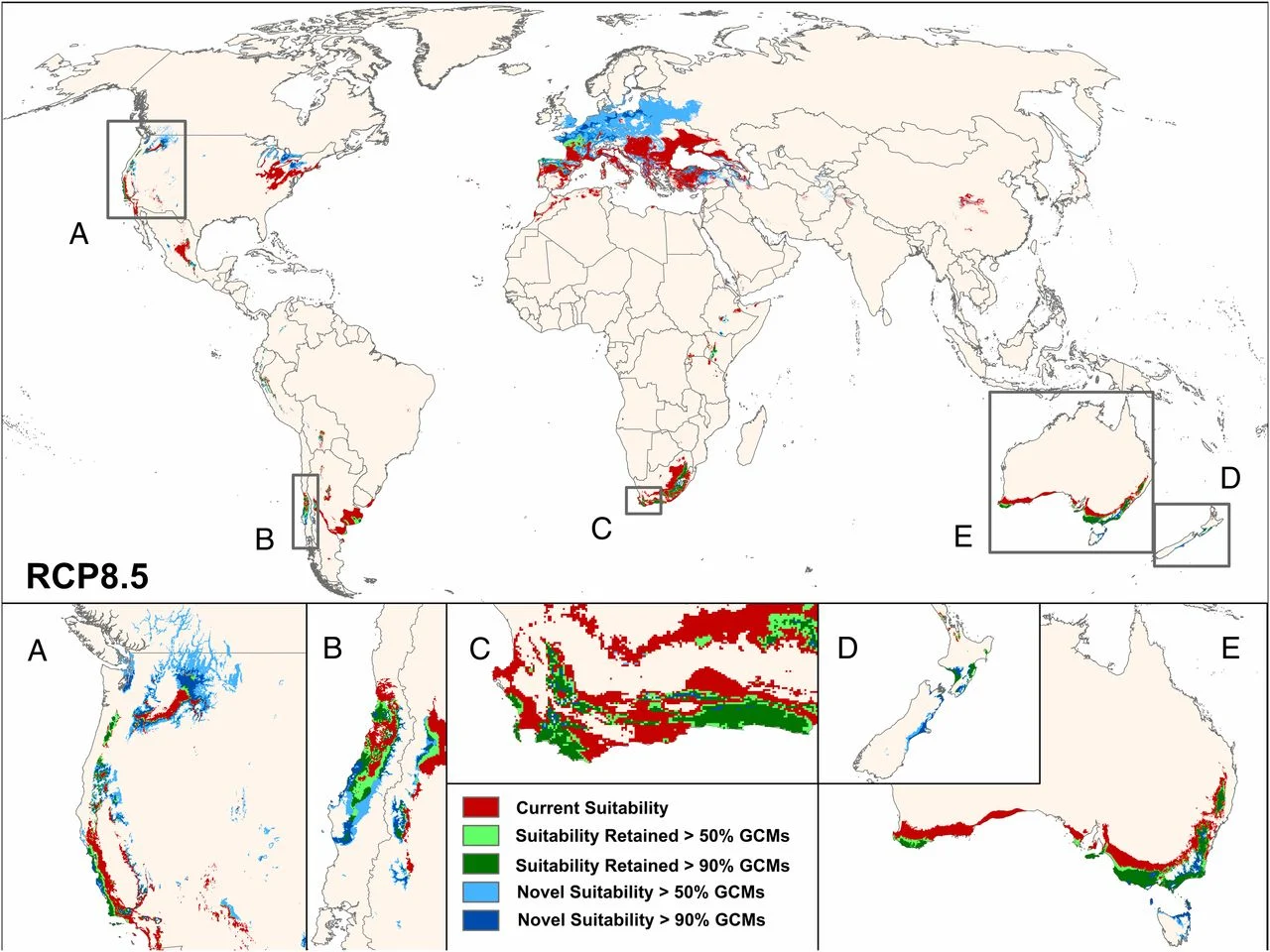

With far hotter summers expected, many of the “traditional” wine-producing regions of the world will lose out. A study from 2013 found that the amount of land suitable for viticulture in those regions drops by 25-73 per cent by 2050 in the worst-case scenario.

But large swaths of the world will become a new frontier for wine-growing as the climactic sweet spot moves further north, and to higher altitudes, and it looks like Canada will gain more vine land than it loses.

Areas in red represent decline in suitability for wine-growing, while areas in blue represent increase in suitability. Credit: Proceedings of the National Academy of Science

In Ontario, the loss of land suitable for vineyards in Niagara will be generally be more than offset by gains in the rest of southwest Ontario. In the West, B.C.’s mountain valleys will also be bigger players.

However, though future producers stand to gain, current producers in Canada's multi-billion-dollar wine industry will take a serious hit, as will the thousands of people who depend on it for employment. And even in those aforementioned new frontiers, it won't be great news for wildlife and local ecosystems that may be impacted by new, sprawling vineyards.

As always, climate change’s impacts will depend on location, but for some areas, warmer summers and earlier springs can mean grapes will ripen earlier. One study covering 400 years of harvest records in France and Switzerland found that, on average, harvests are now happening 10 days earlier than usual. The researchers say that’s good news for France where, traditionally, earlier harvests mean better wines, but it’s not guaranteed; The 2003 harvest happened a month earlier than average, but the wines were “not especially exceptional.”

But as a counterpoint, one winegrower in northern Italy interviewed by Bloomberg noted that wines in the region were becoming “fuller-bodied, more alcoholic, and riper in flavour,” as higher temperatures lower acidity, raise sugar levels and affect other elements in the grapes -- drastically affecting the taste and potentially turning off many wine-drinkers.

Like we said, a double-edged sword. And whichever way it falls, don’t expect your favourite vintage to remain the same.

WATCH BELOW: WHAT HOTTER AND COOLER WEATHER MEANS FOR WHITE OR RED DRINKERS

ICEWINE

Though Canada has a thriving wine industry, we’re not really a big player on the world stage. In fact, we’re number 35 on the list of wine exporters, far behind stalwarts like France, Italy, Spain, Australia, even Chile.

But one fruit of the vine that makes Canada a global standout is icewine. In fact, Canada is the largest producer of it, as the sweet nectar relies on very specific climate sweet spot that’s likelier to be found in Canada than anywhere else.

The beveridge is made from grapes which are partially frozen, requiring temperatures of around -8°C for three consecutive days. It’s highly regulated, and producers don’t have much wiggle room, as the grapes freeze completely around -12°C.

Image: Dominic Rivard/Wikimedia Commons.

But it’s looking like that narrow window is going to become even narrower, or at least less reliable.

A 2015 study by researchers at Canadian universities outlined a whole spate of challenges the icewine industry will have to prepare for, many centred around expected milder winters which would push ideal harvest times from December and mid-January to February and even March. That exposes the grapes for a longer period of time to pests, and impacts juice yield as grapes that are left longer on the vine become more dehydrated. Later harvests also make crop damage from extreme weather and starker freeze-thaw cycles more likely.

Already, research suggests the number of suitable days for picking the half-frozen grapes has been on a downward trend, and in recent years, vintners have grown more sensitive to the problem. A 2018 study found 60 per cent of wine growers believed climate change would have an impact on their business.

WATCH BELOW: HARVESTING HALF-FROZEN GRAPES FOR ICEWINE

However, that same study showed that those who expected an impact said there would be both negative AND positive effects, such as opening up more areas suitable for viticulture, as well as making it easier to grow new varieties of grapes.

As for the unpredictability of the seasons, in recent years vintners have told media that it’s been a challenge, but there are ways to adapt. In the Niagara Region, for example, some growers adapted to the shortened window of opportunity by investing in mechanical pickers, rather than relying on the slower process of picking by hand. Another installed wind machines, that can heat up an area by three or four degrees.

So the challenges do seem to be manageable, though we’d imagine growers would maybe prefer it if the climate behaved itself instead.

WATCH BELOW: WINEMAKERS ARE ADAPTING NEW CREATIVE METHODS BECAUSE OF CLIMATE CHANGE

SCOTCH WHISKEY

For those whose thirst runs toward a glass of whiskey every now and then, the birthplace of that mystic dram is already having to grapple with the expected and current effects of climate change.

It’s not quite all bad: While we’ve already talked about how barley, a key ingredient in Scotch, is set to decline worldwide, a 2016 study found most of the U.K. would actually see stable or even higher yields by the 2050s, even in high-emission scenarios.

But the same study also found that some parts of the U.K. could see a reduction in output due to excessive soil saturation -- including southwestern Scotland. Obviously, barley can be brought in from elsewhere, but that would be more costly -- and more costly inputs mean more costly outputs.

Speaking to Scotland’s Sunday Post, some experts said yields could be increased the old-fashioned way: Leaving fields fallow and planting crops such as oats and peas alongside barley to increase nutrients and reduce the need for pesticides. There’s also the prospect of breeding hardier varieties of barley.

But, barley or no barley, Scotch faces a bigger problem: Many distilleries rely on springwater, and as climate change advances, that’s expected to start running low.

In fact, that’s already happened as recently in 2018, when some distillers had to cut back on production when water levels of springs and rivers ran too low due to prolonged drought. One distiller went the entire month of September without producing anything; They owned a private spring, and it simply went dry. Less snowfall up in the mountains will also leave such springs thirsty when warm weather returns.

We’ve mentioned already that climate change will sometimes be a kind of whiplash, with more periods of extended drought, and individual severe weather events becoming more damaging, and Scotland won’t be an exception. Extreme weather events are expected not only to damage cropland, but also coastal and riverside infrastructure in key Scotch production areas.

As for fighting climate change, or at least blunting its worst effects, the Scotch whiskey industry seems to have banded together to make their little corner of the world economy greener, according to this assessment in Scotch Whiskey Magazine. Aside from reducing emissions, they’ve so far also succeeded in reducing water use by 14 per cent when compared to 2008.

It’s just one industry, in one small country, but it’s not a bad example of industry players at least making the attempt to adapt to the climate change juggernaut.

TEQUILA

Tequila has been skyrocketing in popularity in recent years, which is bad timing, given how the liquor’s source, the cactus-like agave plant, is facing a two-pronged onslaught.

First off, the unassuming Mexican long-nosed bat, a key pollinator for some species of agave, is in dire straits. Due to a combination of the usual factors like human activity, disease and invasive species, they’re considered endangered. A study from earlier this year projected a decline of at least 75 per cent in the overlap in its migratory routes between the southern U.S., and Mexico's agave-producing areas by 2070. Less pollination will harm agave plants in the long run by limiting genetic diversity.

WATCH BELOW: WITHOUT BATS THERE WOULD BE NO TEQUILA

Worsening the issue: The agave plant was already been known to have been in dire strengths due to rising heat. A 2014 study found temperatures had risen an average 1.1C from 1998, and it’s not got any cooler since.

You’d think a plant that evolved to live in deserts and semi-deserts wouldn’t sweat that increase, but the heat does impact the life cycle by harming the development of the plants’ flowers and embryo sacs, harming their fertility.

Not only that, those plants that do grow to adulthood are maturing faster, from 8-10 years to 5-7 years, reducing their sugar content and worsening the final tequila product.

A bleak outlook for the agave — which is ironic, given how scientists are starting to look at it as the key to agricultural survival in a warmer world.

Like other desert species, the agave ‘breathes’ by opening its stoma at night to prevent moisture loss during the heat — the specific opposite of most other plant species. That habit has scientists taking a second look at the agave’s genetic code, to see whether that trait can be transferred to other plants. In a 2016 study, the authors were hopeful the result would be plants that would be more resistant to the higher temperatures and more frequent droughts.