Using data from the Arctic to improve hurricane forecasting

Forecasters are continually looking for new and better ways to predict hurricanes. And now, they're focusing their search on distant locations.

It's been an exceptionally active hurricane season in the Atlantic basin. Since June, we've seen 25 storms and nine hurricanes, three of them major.

Forecasters are continually looking for new and better ways to predict hurricanes. And now, they're focusing their search on distant locations.

On September 5, 2017, Hurricane Irma strengthened into a Category-5 storm becoming, at the time, the most powerful Atlantic hurricane in recorded history, only to be surpassed by Hurricane Dorian two years later.

When Irma made landfall on Barbuda on September 6, it packed maximum sustained winds that peaked at 285 km/h, damaging 90 per cent of the buildings on the island. It destroyed nearly all forms of communication and left more than half of the population homeless.

A few days later, Irma turned northward and made landfall in southwestern Florida.

Understanding the timing and the position of the northward turn was important because it helped Floridians prepare for impact and potential evacuations. Forecasting the turn was a challenge, though, due to uncertainty surrounding the prediction of Irma's upper-level trough.

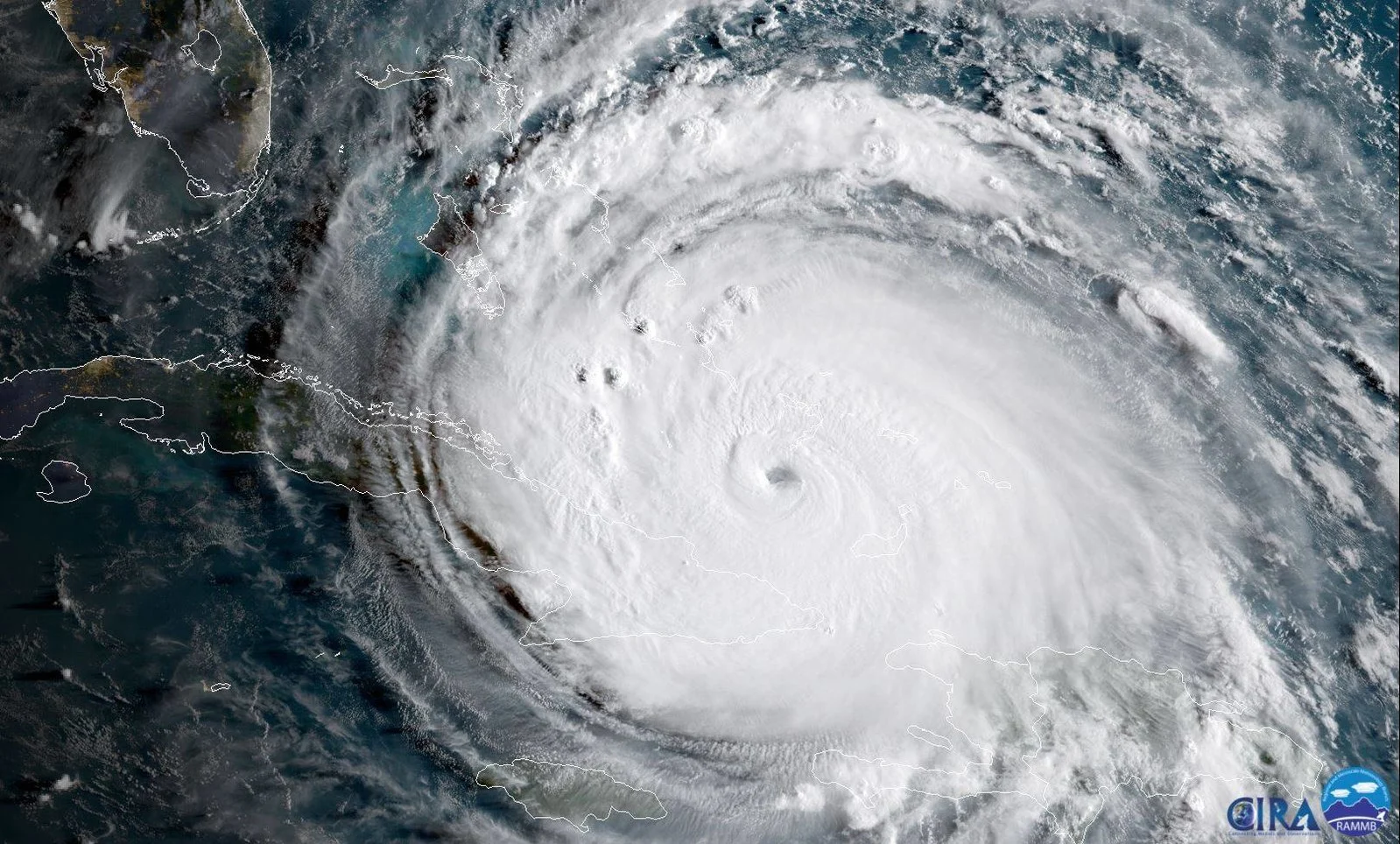

GOES-16 satellite image shows Hurricane Irma passing the eastern end of Cuba 08/09/2017. Photo by NOAA.

In a new paper published in the journal Atmosphere, a team led by the Kitami Institute of Technology in Japan found that collection of additional meteorological data from as far away as the Arctic could improve forecasts of future storms like Irma.

For their paper, researchers examined the accuracy of forecasts for 29 Atlantic hurricanes between 2007 and 2019, focusing on hurricanes that moved north in response to upper-level atmospheric circulation over mid-latitudes and approached the US.

"During the forecast period Hurricane Irma in 2017, there was large meandering of the jet stream over the North Pacific and North Atlantic, which introduced large errors in the forecasts. When we included additional radiosonde observation data from the Research Vessel Mirai collected in the Arctic in the late summer of 2017, the error and ensemble spread of the upper-level trough at the initial time of forecast were improved, which increased the accuracy of the track forecast for Irma," lead author Kazutoshi Sato explains in a statement.

VIDEO: IRMA AS SEEN FROM THE INTERNATIONAL SPACE STATION | SEPTEMBER 5, 2017:

Researchers say forecasting was also improved by collecting data that was taken near the hurricane and over the Arctic Ocean from the US Air Force Reserve and the Aircraft Operations Center of NOAA.

"Our findings show that developing a more efficient observation system over the higher latitudes will be greatly beneficial to tropical cyclone track forecasting over the mid-latitudes, which will help mitigate the human casualties and socioeconomic losses caused by these storms," co-author Jun Inoue, an associate professor of National Institute of Polar Research says in a statement.

The Atlantic hurricane season runs from June to the end of November. According to NOAA's Hurricane Research Division, the Atlantic 'season' has been in place since 1965 and provides a broad definition encompassing about 97 per cent of the storms and hurricanes that form in the Atlantic in a given year.