Pluto's mountain ice caps may result from weather flipped upside-down

"It is particularly remarkable to see that two very similar landscapes on Earth and Pluto can be created by two very dissimilar processes," says one researcher.

New research into Pluto's mountain ice caps has revealed how this bizarre little world turns meteorology onto its head.

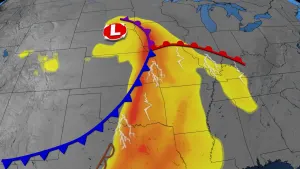

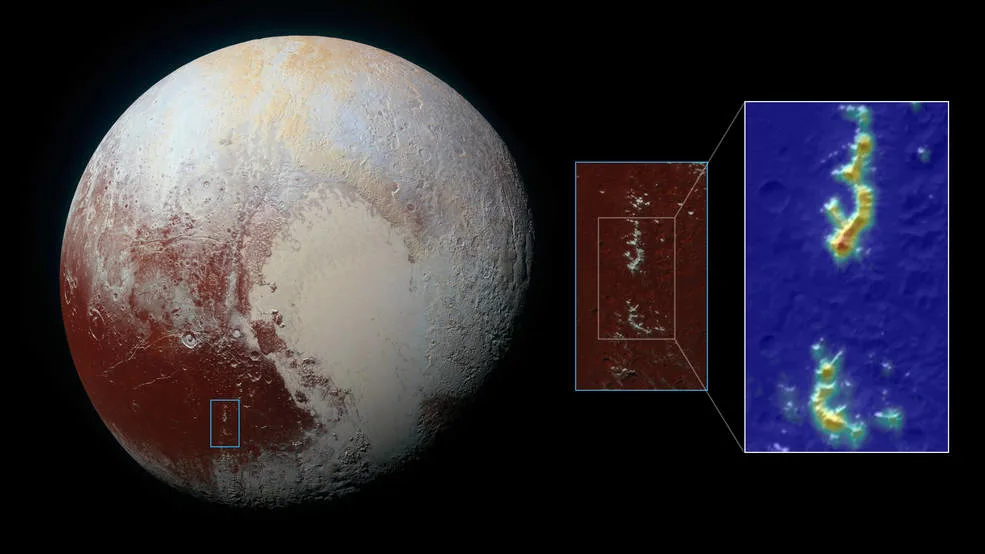

When NASA's New Horizons spacecraft flew past Pluto in 2015, it snapped images that showed mountain ranges on the dwarf planet that appeared brightly-capped with ice and snow. Given that Pluto is very different from Earth, how can we see two very similar sights on both worlds?

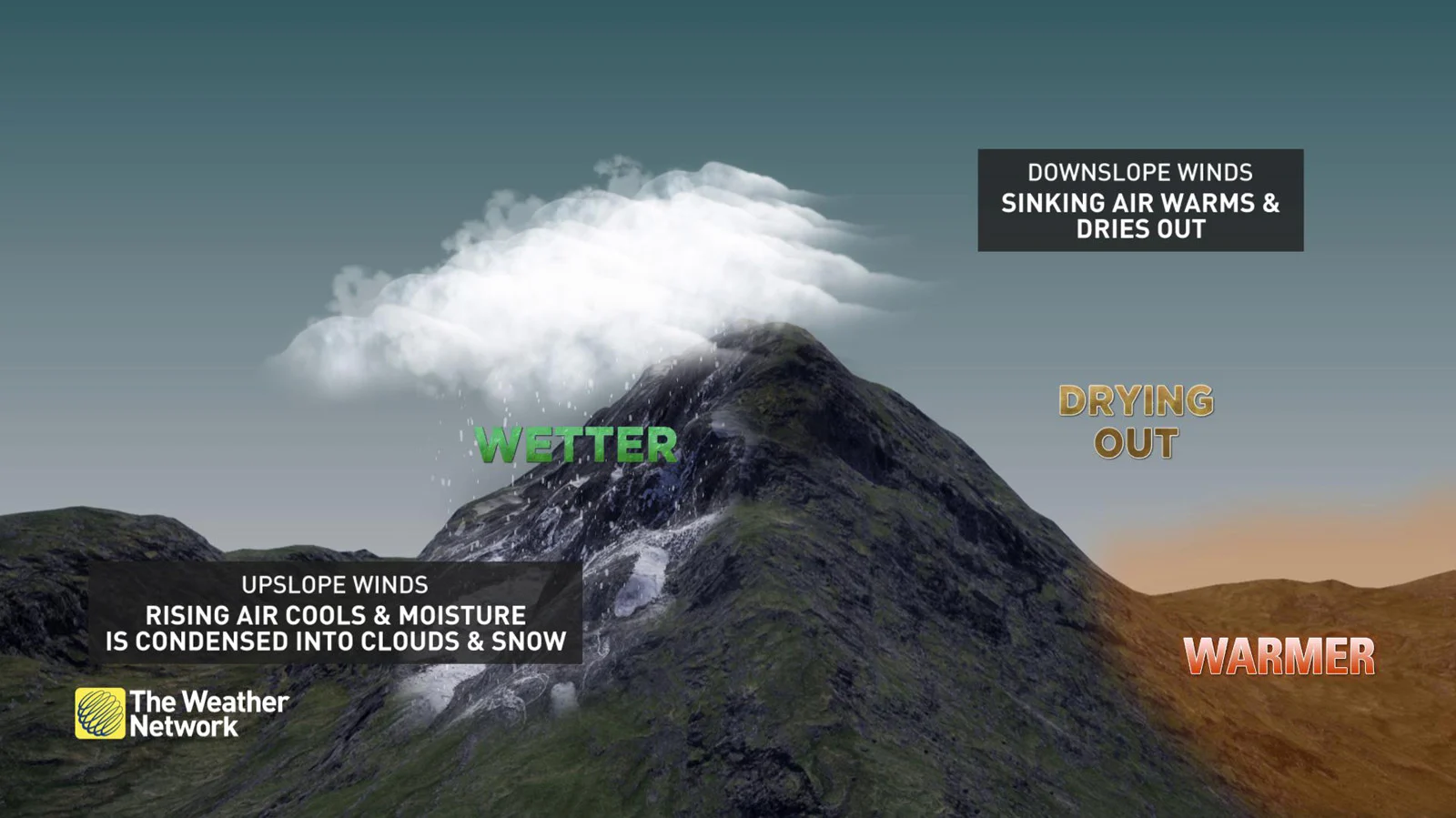

On Earth, the reason why we see snow-capped mountains is pretty straightforward. Winds carry humid air up a mountainside. This causes the air to cool. The cooling causes water vapour in the humid air to condense into clouds. Eventually, snow falls from those clouds onto the mountaintop. Due to the relatively thick atmosphere absorbing heat from the ground, this cooling with altitude also cools the ground, so the snow sticks around on the mountaintop, sometimes all year long.

On Pluto, things are topsy-turvy by comparison.

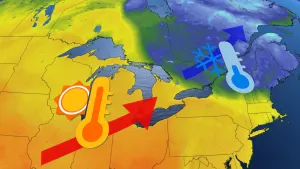

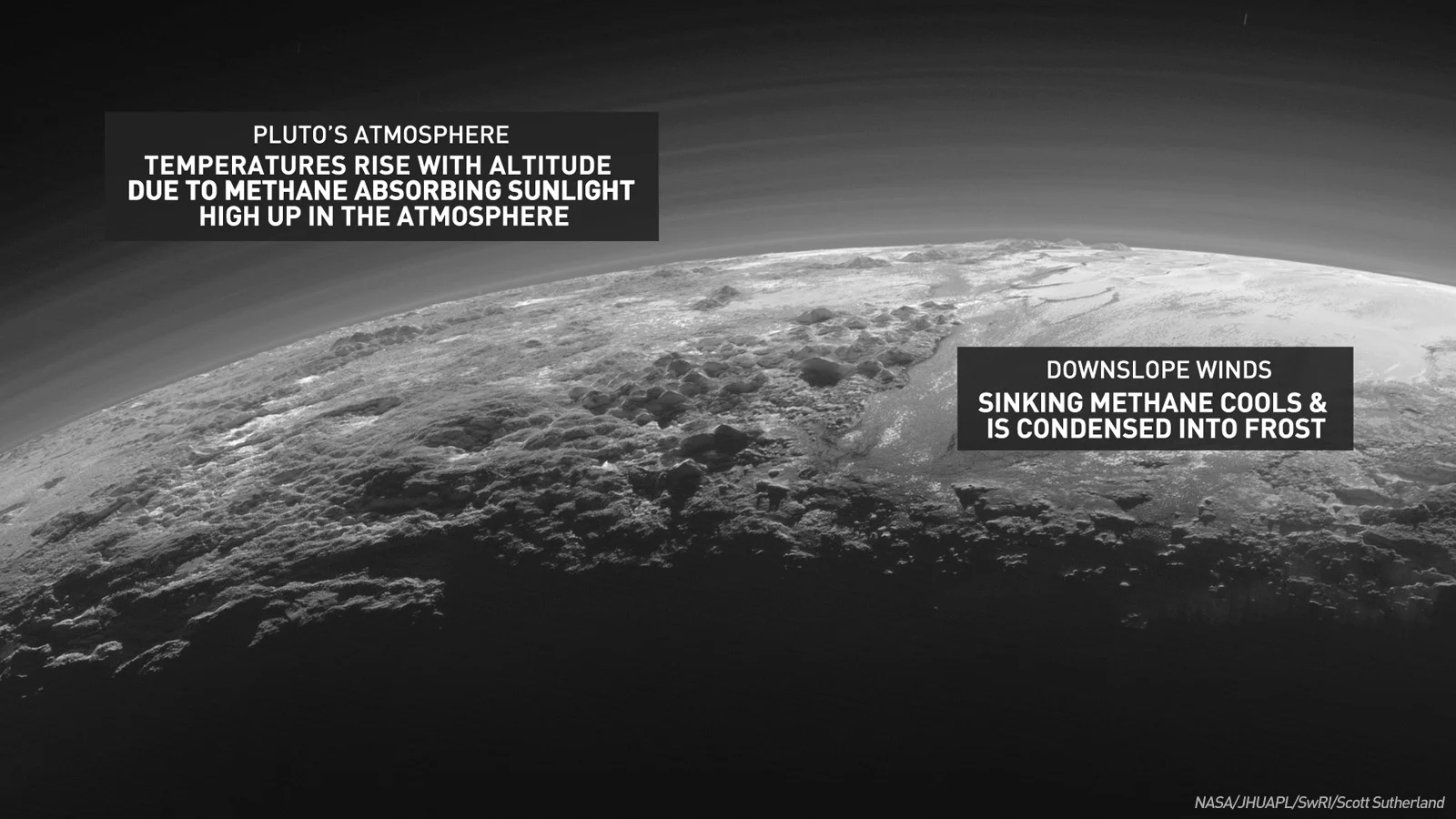

Pluto's thin atmosphere is mainly composed of nitrogen, but it has concentrations of methane high above the surface. This methane absorbs solar radiation at high altitudes, which leaves the surface colder. As a result, the temperature profile is opposite to Earth - temperatures increase with height instead of decrease.

By running detailed climate simulations, developed at Laboratoire de Météorologie Dynamique, in Paris, France, a team of scientists has figured out how Pluto could still develop ice-capped mountains, even with this 'backwards' situation.

Based on their study, the researchers propose that sinking air - rather than rising air - drives Pluto's weather. So, as atmospheric circulations cycle the air around, concentrations of methane sink towards the colder surface. The air cools as it descends, and methane freezes out of the air - turns directly from a gas into solid ice crystals - and settling as frost onto the mountain tops.

This image of mountains on Pluto, snapped by the New Horizons spacecraft just after it passed the dwarf planet on July 14, 2015, shows the terrain back-lit and reveals numerous hazy layers of the atmosphere. Text added to the image details how Pluto's unusual atmospheric processes produce methane ice-caps on mountains. Credit: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI

As the research team wrote, once a fresh patch of methane frost grows to a thickness of a few millimetres, the ice appears to reflect more than half of the incoming sunlight back towards space. The mountaintop even further, as a result, causing the air above it to cool further as well. This promotes even stronger sinking air, producing more methane frost.

"Overall, the formation of CH4 frost on top of Pluto's mountains appears to be driven by a process completely different from the one forming snow-capped mountains on the Earth, according to our model," they wrote.

According to the research, this same process may also be responsible for bright deposits seen along Pluto's craters rims and the bizarre 'bladed terrain' seen in the dwarf planet's equatorial region.

Watch below: NASA details Pluto's bizarre bladed terrain

"It is particularly remarkable to see that two very similar landscapes on Earth and Pluto can be created by two very dissimilar processes," Tanguy Bertrand, the lead author of the study, who is a postdoctoral researcher at NASA's Ames Research Center, said in a press release. "Though theoretically objects like Neptune's moon Triton could have a similar process, nowhere else in our solar system has ice-capped mountains like this besides Earth."