There's still a chance to see the Perseid Meteor Shower! Here's how to watch

Watch for fireballs streaking across the sky!

Still good for watching one of the best meteor showers of the entire year? The Perseid Meteor Shower is going on right now, and there are more chances to catch the show, even after its Tuesday night peak.

The Perseids are capable of delivering up to 100 meteors per hour at their peak, when viewed under ideal conditions. Now, in the days following the peak, that number is ramping down. We can expect to see around 60 meteors per hour on Wednesday night. On Thursday night, it will drop to around 50 per hour, and it will continue to diminish for the rest of the week. These numbers represent the ideal - viewed under absolute dark, clear skies, with the radiant directly overhead. The typical viewer, watching from a rural location, will likely see about half that number, which still one meteor every couple of minutes or so.

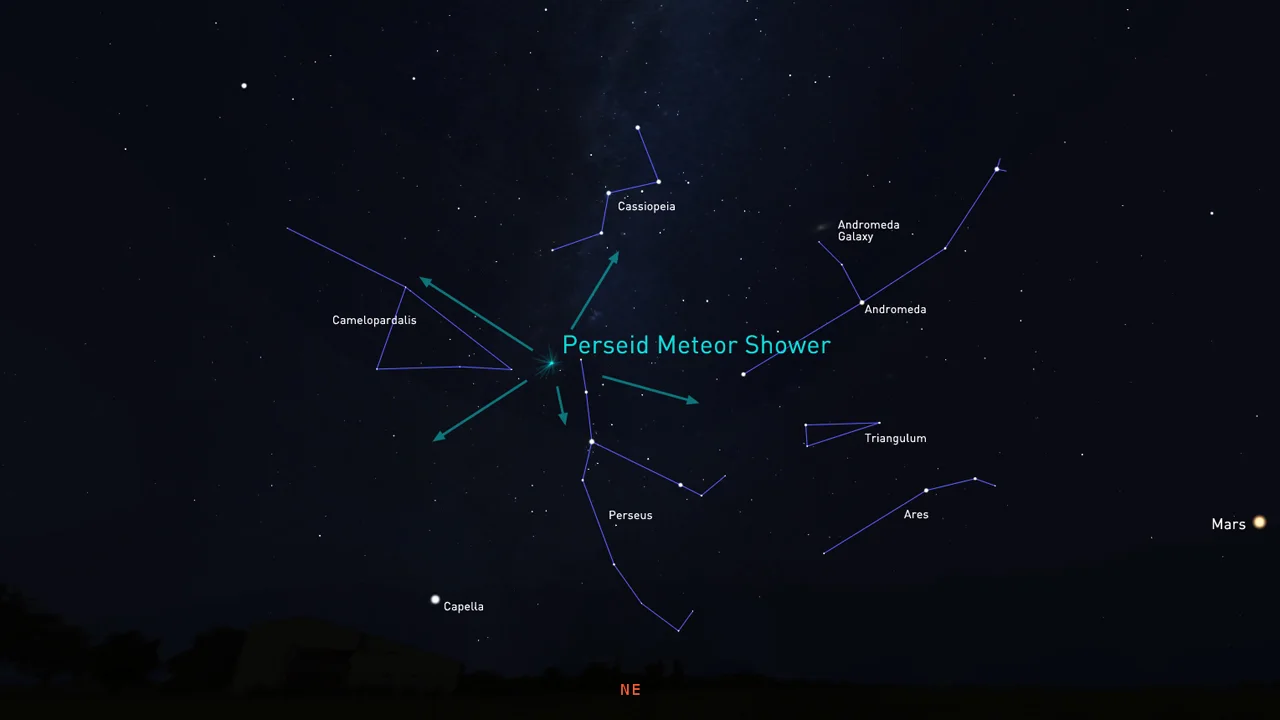

The radiant of the Perseids - the position in the sky that the meteors appear to originate from - never sets below the horizon at this time of year. So, it's only a matter of waiting for the Sun to completely set to watch.

The location of the Perseids radiant at around midnight on August 11-12. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

The absolute best time to watch the Perseids is usually in the hours between midnight and dawn. With the Moon rising around midnight right now, right now, its light will make it more challenging to see some of the dimmer meteors during those hours. Thus, viewers may see a better show between sunset and midnight each night this week.

As for the weather, the map above shows the expected cloud conditions across Canada for Wednesday night.

WATCH FROM ANYWHERE

If your skies are cloudy or you miss out on the opportunity to get outside for this event, don't worry! You can see the meteor shower from various online sources!

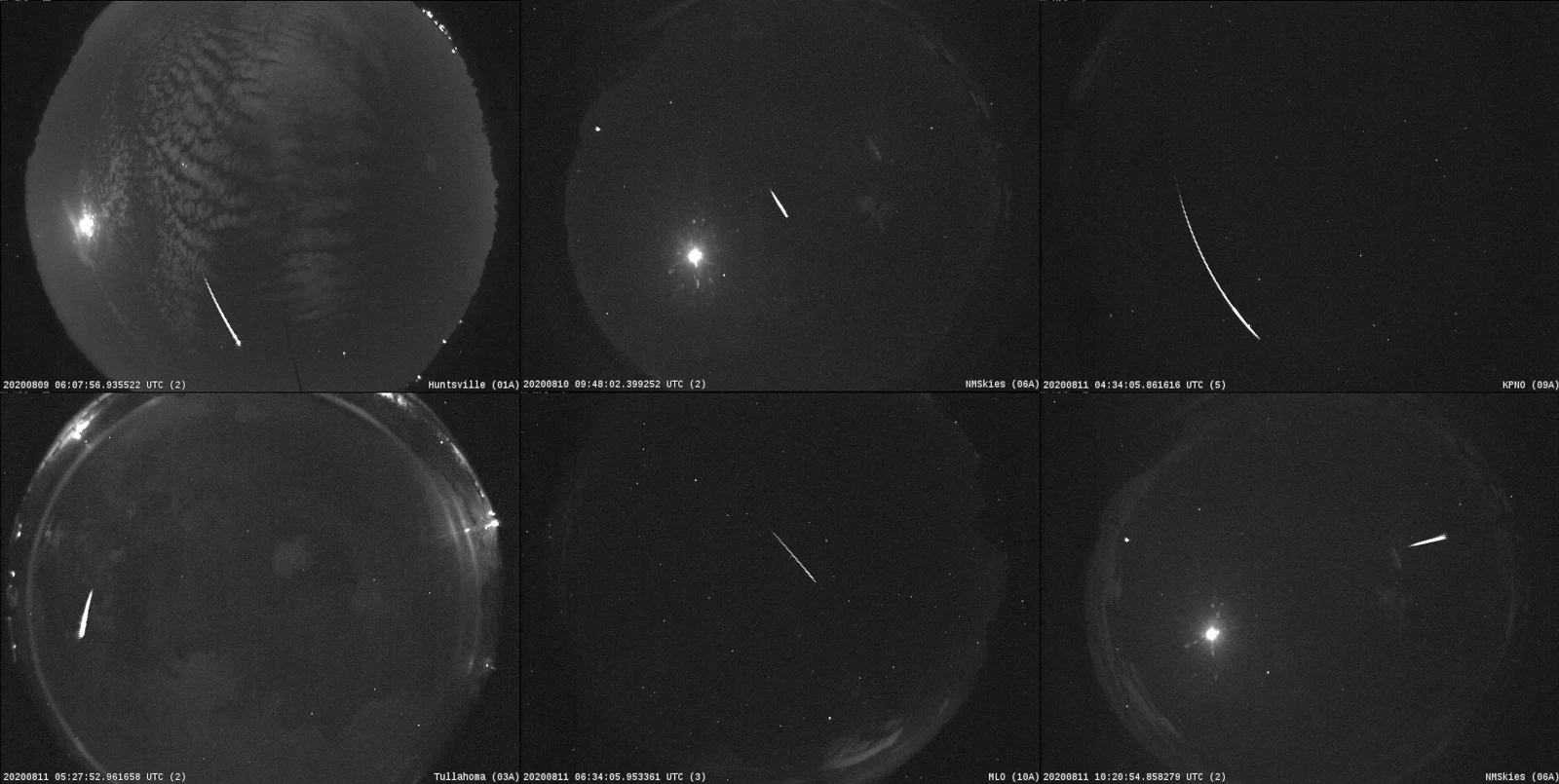

According to NASA's Watch the Skies blog, each morning, the public can also view fireballs recorded by NASA's All Sky Fireball Network from the night before. Use the links along the left side of the page, to view the collection of fireball movies recorded each night (going back three weeks!), or watch the liveviews each night to see the action as it happens.

This selection of six images captured by NASA's ALl Sky Fireball Network feature Perseid fireballs from the morning of Wednesday, August 11, 2020. Credit: NASA

The SpaceWeather website also has a collection of Perseid fireball images, submitted by astrophotographers around the world.

Finally, there's a fairly unusual and unique way to witness a meteor shower, day or night - using Meteor Radar! Live Meteors on YouTube live streams nightly, allowing us to see and listen to the radar echoes of meteoroids hitting the top of the atmosphere.

Read on for tips on getting the most out of watching a meteor shower.

SPECTACULAR PERSEIDS

The Perseids are not only known for the number of meteors that it produces. There are two other ways this meteor shower distinguishes itself from the others.

First, it is the annual meteor shower with the highest number of fireballs. These are very bright meteors, at least as bright as the planet Venus, which usually last for quite a bit longer than typical meteors.

Watch below: An all-sky camera captures a brilliant Perseid fireball

The second is the ability of some Perseid meteors to leave behind a phenomenon known as a persistent train.

A persistent train appears as a trail of glowing 'smoke', which remains visible after the meteor has done out. They can last from a few seconds, to several minutes, or possibly up to an hour or longer. While they have been observed fairly often, they have only rarely been recorded. Thus, with little hard evidence to study the phenomenon, scientists have only been able to narrow down their cause to one of two likely reasons: ionization and chemiluminescence.

In the case of ionization, an exceptionally fast-moving meteoroid is capable of producing enough energy to actually strip electrons from the air molecules it encounters, leaving them in an ionized state. When these ions pick up a stray electron to balance out their charge, they release a small burst of light. Chemiluminescence, on the other hand, occurs when metals vaporizing off the surface of a meteoroid chemically react with ozone and oxygen, producing a glow. Since these processes take much longer than the original meteor flash, the train can persist for some time after the flash goes out.

Watch below to see a persistent train produced by a December Geminids meteor

One of these explanations may account for these glowing trains, or both may cover different occurrences, at different times, and even between individual meteors. It will apparently take more sightings and recordings of this phenomenon to explain them fully.

WHAT'S GOING ON HERE?

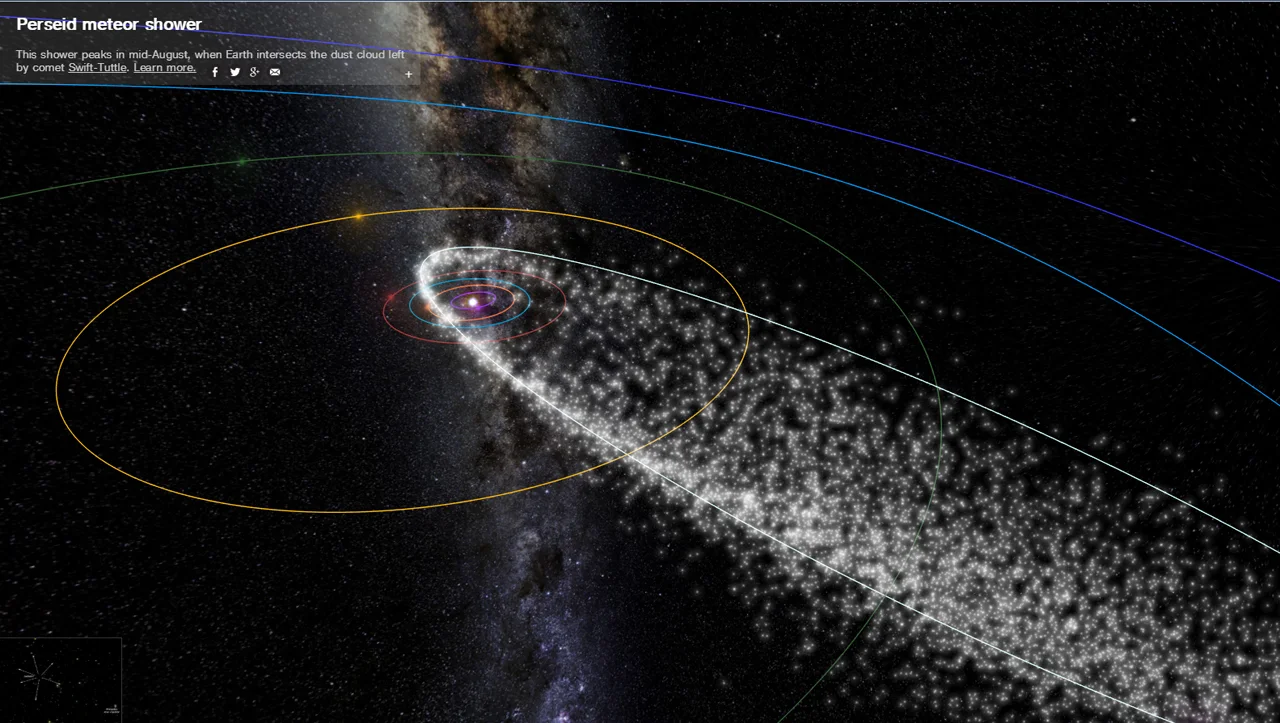

Meteor showers happen when Earth encounters a stream of ice, dust and rock left behind from a comet (or sometimes a special kind of asteroid) passing through the inner solar system. As Earth sweeps through the stream, the bits of debris plunge into the planet's atmosphere, travelling anywhere from 54,000 to 255,000 kilometres per hour. At that speed, these meteoroids compress the air molecules in their path, squeezing them together until they glow, white-hot.

The bigger the piece of debris, the brighter and longer-lasting the meteor will be.

This view of the solar system shows the debris stream of Comet Swift-Tuttle. The orbit of Earth is in blue. Credit: meteorshowers.org

The Perseids occur every year between July 17 and August 26, as Earth passes through the stream of debris from a comet known as 109P/Swift-Tuttle. Comet Swift-Tuttle swings around the Sun every 133 years and was last seen in 1992. On August 11-12, Earth encounters the debris stream's densest part, resulting in the highest number of meteors observed during the shower.

METEOR? METEOROID? METEORITE?

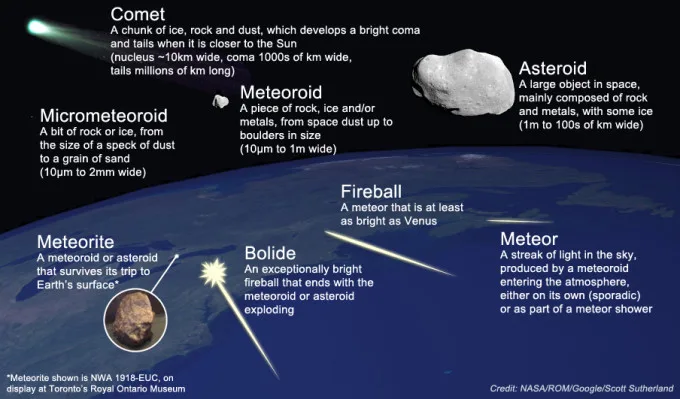

The bright streaks seen from these showers are called meteors.

A meteoroid is a piece of dust, rock or ice floating through space, left over from the formation of our solar system. The smallest - only a few millimetres wide - tend to be called __micrometeoroids. Anything larger than a metre in diameter is usually called an asteroid.

A primer on meteoroids, meteors and meteorites. Credits: Scott Sutherland/NASA JPL (Asteroids Ida & Dactyl)/NASA Earth Observatory (Blue Marble)

The more massive an object is as it enters Earth's atmosphere, the brighter the resulting meteor will be. The brightest are called fireballs, while a fireball that ends with an explosion is known as a bolide.

Some fireballs and bolides result in bits of the meteoroid reaching to the ground. When these are found, they are called meteorites.

Related: Got your hands on a space rock? Here's how to know for sure

TIPS FOR WATCHING A METEOR SHOWER

Here is an essential guide on how to get the most out of meteor shower events.

First off, there's no need to have a telescope or binoculars to watch a meteor shower. Those are great if you want to check out other objects in the sky at the same time - such as Jupiter, Saturn and Mars. When watching a meteor shower, though, telescopes and binoculars actually make it harder to see the event, because they restrict your field of view.

Here's the three things needed for watching meteor showers:

Clear skies,

Dark skies, and

Patience.

Even a few hours of cloudy skies can ruin an attempt to see a meteor shower. Since the weather is continually changing, be sure to check for updates on The Weather Network on TV, on our website, or from our app.

Related: Want to find a meteorite? Expert Geoff Notkin tells us how!

Living in cities makes it very difficult to see meteor showers. If you live in a suburban area and have a dark back yard, shielded from street lights by trees and surrounding houses, you may see the brightest meteors. It's best, though, to get as far away from city light pollution as possible.

For most Canadians, simply driving out into the surrounding rural areas is usually good enough to get under dark skies. However, if you live anywhere from Windsor to Quebec City, that is going to be more difficult. Getting far enough outside of one city to escape its light pollution, unfortunately, tends to put you under the light pollution dome of the next city over.

Watch below: What light pollution is doing to city views of the Milky Way

In these areas, there are a few dark sky preserves. A skywatcher's best bet for dark skies is usually to drive north and seek out the various Ontario provincial parks or Quebec provincial parks. Even if you're confined to the parking lot, after hours, these are usually excellent locations to watch (and you don't run the risk of trespassing on someone's property).

Once you've verified you have clear skies, and you've gotten away from light pollution, this is where having patience comes in.

For best viewing, give your eyes time to adapt to the dark. Typically, this takes about 30 minutes of avoiding any source of bright light (includes cellphone screens). Just looking up into the sky during this time works fine, and you may even catch some of the brighter meteors in the process.

Lastly, the graphics presented for meteor showers often give a 'radiant' point on the field of stars, showing where the meteors originate. Meteors can flash through the sky anywhere above your head, though. So, don't focus on any particular point in the sky. Just look straight up and take in as much of the sky as you can, all at once. Also, since our peripheral vision tends to be better at night, you may be surprised at how many meteors you can catch from the corner of your eye!

Sources: American Meteor Society | RASC | With files from The Weather Network