'Upside-down' rivers are eroding Antarctica's ice shelves from below

Climate models and forecasts do not yet account for this troubling scenario, which is already underway

Ice shelves along the coastlines of west Antarctica are already suffering a worrisome amount of ice loss, but researchers have identified a new way that appears to be making this ice loss even worse.

In a new study published this week, scientists working with the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES) at the University of Colorado Boulder, show how 'upside-down rivers' of warm ocean water are carving into ice shelves from below, making them more vulnerable to collapse.

"Warm water circulation is attacking the undersides of these ice shelves at their most vulnerable points," said study lead author Karen Alley, according to a CIRES press release. "These effects matter," she added. "But exactly how much, we don't yet know. We need to."

Previous studies have shown how warm subsurface ocean water is whittling away at ice shelves from below. Some of this warm water is due to plumes that rise up from the deeper layers of the ocean.

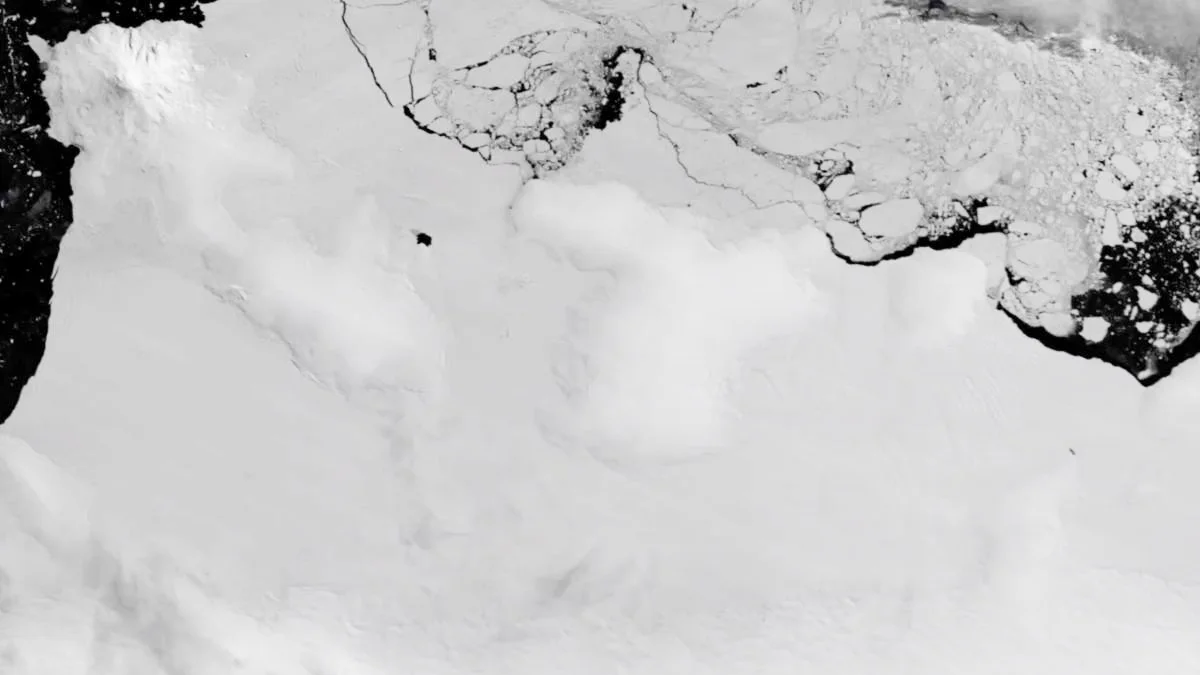

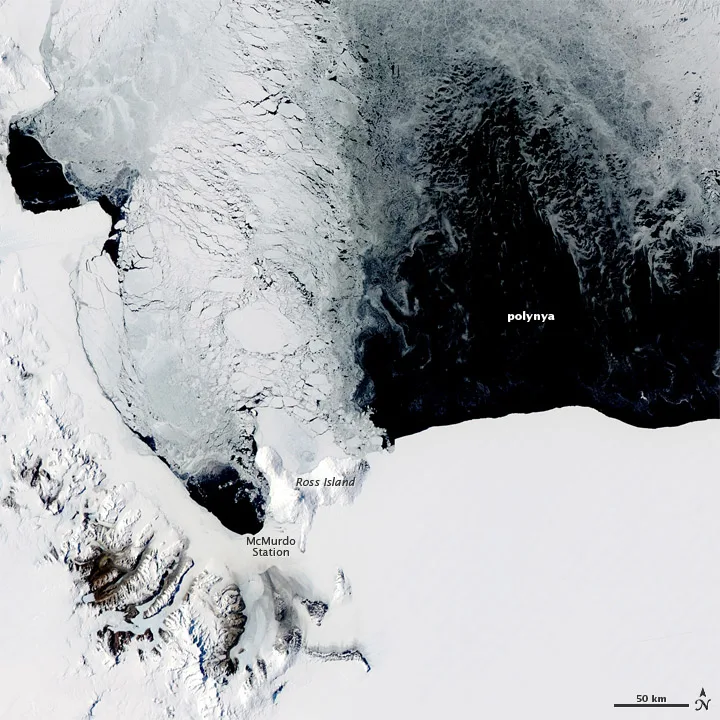

When these warm water plumes encounter sea ice, they melt the ice to form open patches known as 'polynyas'.

NASA’s Aqua satellite captured this natural-color image of a polynya off the coast of Antarctica, near Ross Island and McMurdo Station on November 16, 2011. Credit: NASA Earth Observatory

When a plume rises surfaces under an ice sheet, it floats on top due to having a lower density than the cold water beneath it, and flows into the higher points in the uneven underside of the ice sheet. In some cases, the flowing warm water can carve channels into the underside of the ice, forming an 'upside-down river', which can be more than a kilometre wide and tens of kilometres long.

This new work by Alley and her team is showing how these warm water plumes are much more common under ice shelves than previously thought, and can actually 'take advantage' of natural weak points in the ice shelf, to speed up the process of its collapse.

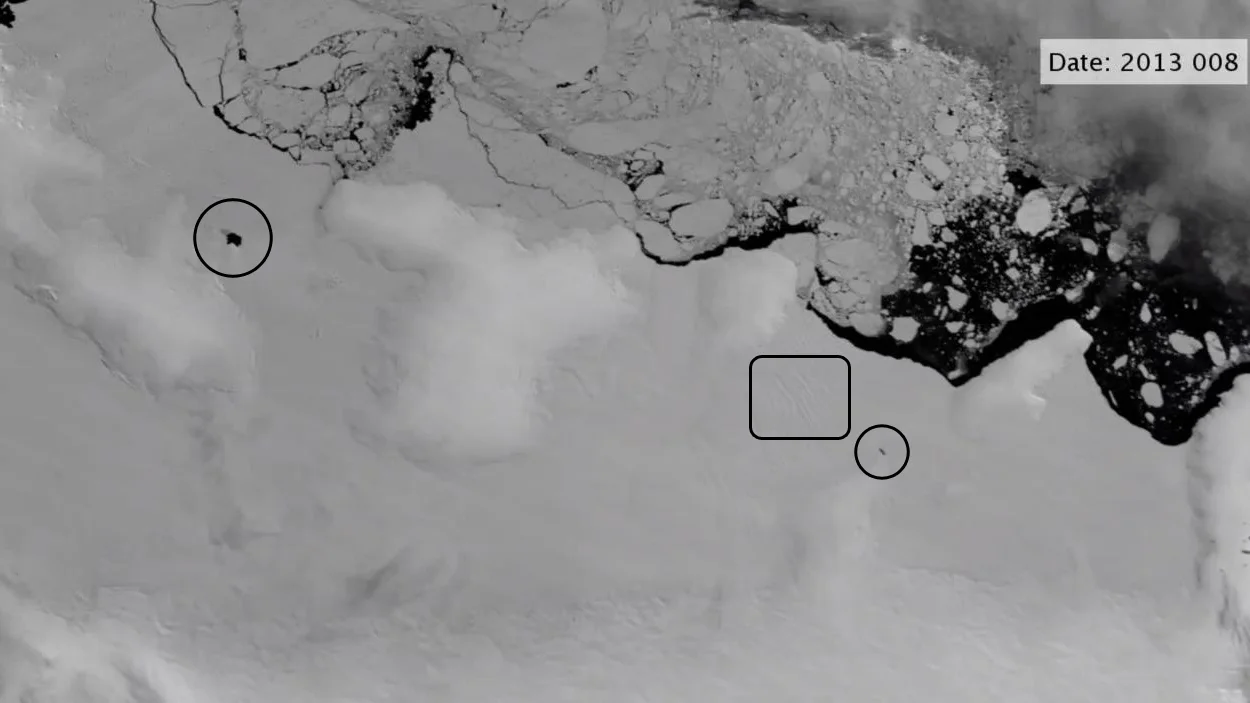

According to the study, when fast-moving glacial ice flows down from land to form an ice shelf over the water, shear stresses along the margins of the shelf open up cracks and crevasses in the ice. Based on satellite imagery taken over years, Alley and her co-authors found that these 'upside-down rivers' - formally called 'basal channels' - are much more likely to form along the crevasses at these margins.

This satellite image of the East Getz Ice Shelf shows two persistent polynyas opened up in the ice (circled), with the wrinkles of basal channels evident along the surface of the ice sheet (inside the rectangle). Credits: Karen Alley/The College of Wooster and NASA MODIS/MODIS Antarctic Ice Shelf Image Archive at the National Snow and Ice Data Center, CU Boulder/Scott Sutherland

"Like scoring a plate of glass, the trough renders the shelf weak," study co-author Ted Scambos, who is a CIRES senior scientist at CU Boulder, said in the press release, "and in a few decades, it's gone, freeing the ice sheet to ride out faster into the ocean."

While ice breaking away from ice shelves does not directly impact sea levels, the melting of that freshwater ice into the saltwater ocean does cause a small amount of sea level rise.

Of greater concern, as Scambos points out, is the effect if an ice sheet completely collapses, allowing more ice to quicly flow down from the glacier. That new ice flowing from on land to over the water has a direct effect on sea level rise.

If the effects of these 'upside-down rivers' are not yet accounted for by climate models and forecasts, as the researchers say, we may not have the full story when it comes to sea level rise in the future.

Sources: CIRES | NASA Earth Observatory