The mystery behind what powers the Northern Lights has now been solved

New research shows that solar particles get their aurora-sparking energy by 'surfing' on plasma waves.

New research into the Northern and Southern Lights has uncovered the energy source that powers these remarkable displays, solving a long-standing mystery about their origins.

Each display of the auroras that stretches across the night sky is caused by a bombardment of solar particles from space. These particles originate from the solar wind and become trapped in Earth's geomagnetic field as they flow past the planet. They then stream down into the upper atmosphere, where they smack into atoms and molecules of oxygen and nitrogen, causing them to emit tiny flashes of coloured light. It's these flashes of light — millions upon millions of them — that combine to form the auroras.

This view of the Aurora Borealis was captured from Yellowknife, NWT, on October 24, 2011. Credit: AuroraMAX/Canadian Space Agency

One vital piece of this process has been missing up until now, though. When the solar particles (typically electrons) become trapped in Earth's magnetic field, they don't have the energy required to produce auroras.

So, somewhere between becoming trapped and when they stream down into the atmosphere, they must gather tremendous amounts of energy. The question is, what is the source of this energy?

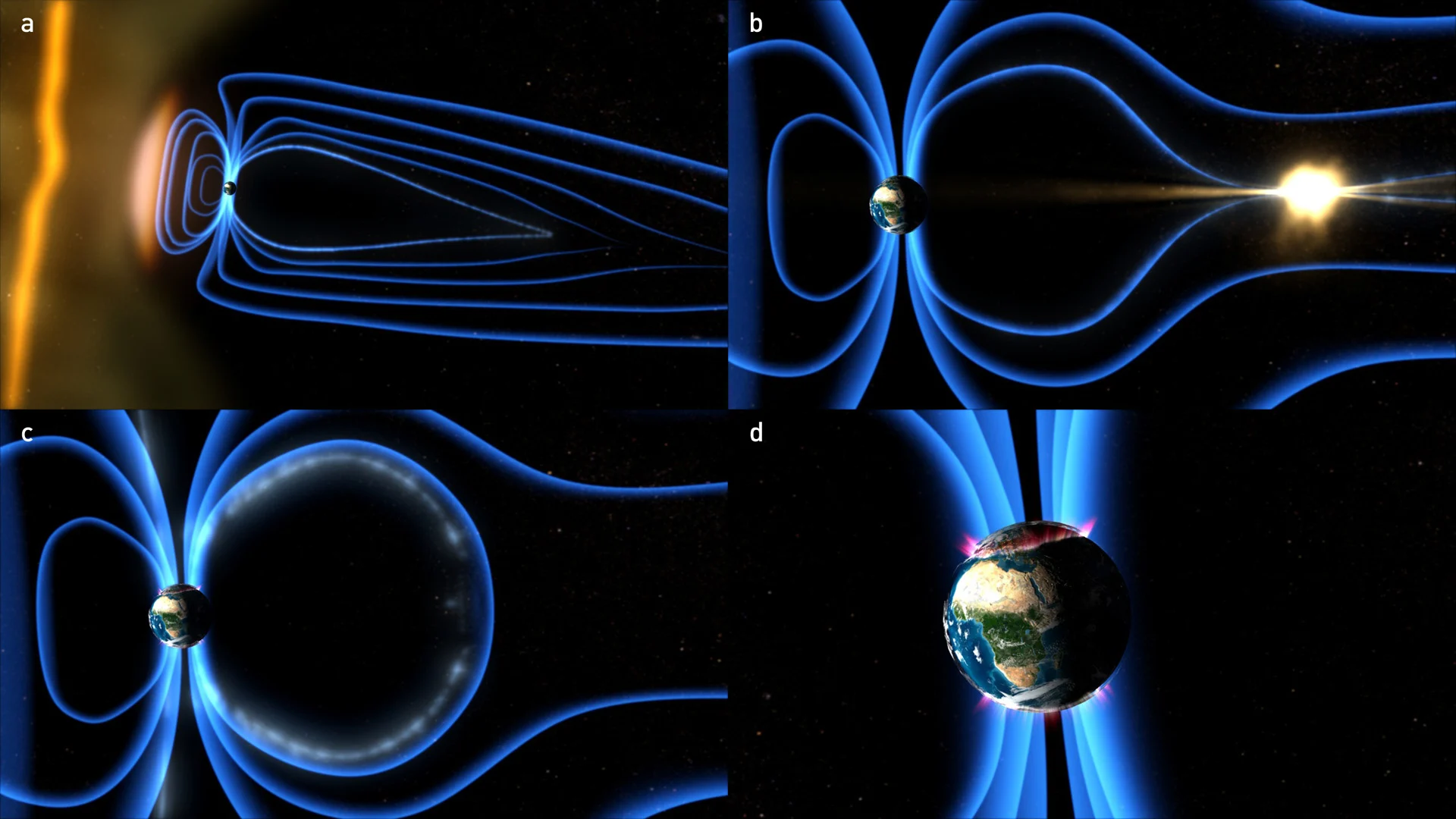

The basic processes that lead to auroras are illustrated here, from (a) solar wind particles becoming trapped in Earth's magnetic field, (b) a "magnetic reconnection" of as magnetic field lines are pressed together, (c) particles trapped on that field line stream down into the atmosphere, and (d) produce auroras. Credit: NASA

According to NASA, satellite measurements of the auroras and Earth's magnetic field led to the idea that this energy could come from a specific type of plasma wave, known as Alfven waves.

First proposed in 1942 by Swedish physicist Hannes Alfven, an Alfven wave is a wave of motion travelling through a plasma, due to the influence of electric and magnetic fields. In the case of auroras, the plasma is the particles flowing on the solar wind, and the magnetic field is Earth's geomagnetic field. As the two interact, it generates a physical wave of motion through the plasma, which travels along the magnetic field.

Even with satellites spotting Alfven waves at the same time that auroras were occurring, the measurements couldn't directly link the two phenomena.

To more directly test this connection, Dr. Jim Schroeder, an Assistant Professor of Physics at Wheaton College in Illinois, led a team of scientists in performing laboratory experiments. Using the Large Plasma Device (LAPD) at UCLA's Basic Plasma Science Facility, they sent Alfven waves travelling down the device's chamber at high speed, matching how these waves travel in space. Observing the electrons in the plasma chamber, they saw the particles being picked up and carried along by the Alfven waves, drawing energy from the waves as they 'surfed' along.

"Picture electrons surfing on waves," Schroeder said in a Wheaton College press release. "Just as a surfer gains speed on an ocean wave, we found that electrons are propelled from space toward Earth by powerful electromagnetic waves."

Their research was just published in the journal Nature Communications and is being presented this week at the 238th annual meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

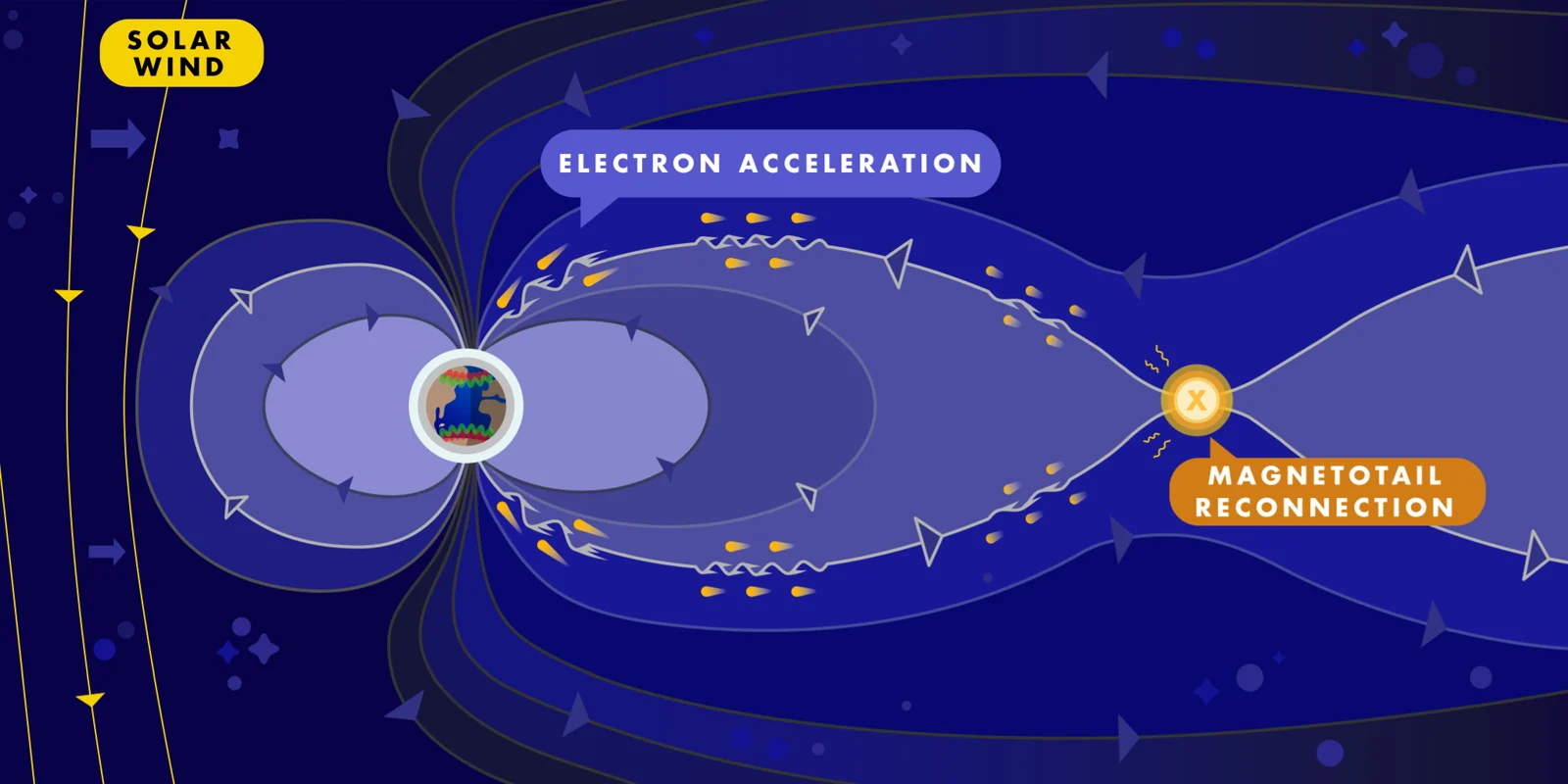

This diagram shows the same basic processes of the solar wind producing auroras, but adding in the vital component of Alfven waves travelling down the magnetic field towards Earth. These Alfven waves pick up electrons along the way, accelerating them and providing them with the energy they need to produce vivid auroras. Credit: Austin Montelius, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, University of Iowa

"The idea that these waves can energize the electrons that create the aurora goes back more than four decades, but this is the first time we've been able to confirm definitively that it works," study co-author Craig Kletzing, a professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Iowa, said in a press release. "These experiments let us make the key measurements that show that the space measurements and theory do, indeed, explain a major way in which the aurora are created."