Massive solar storm set to spark auroras across Canada

A spooky Halloween light show may shine in our skies thanks to an immense eruption from the Sun.

We may be in for a special Halloween treat on Sunday night. Auroras may be dancing across our skies thanks to an immense solar storm the Sun blasted out into space.

Update (Nov 4): although the solar storm did arrive at Earth, it took longer to reach us than space weather forecasters had anticipated. Perhaps as a result of its slower speed, and possibly due to the effects of it passing through a denser region of the solar wind, the CME's impact on Earth's geomagnetic field was weaker than predicted. Storm levels only reached G1 (weak), rather than the forecast G3 (strong) levels, thus the auroras produced remained farther north. As we are just entering a new solar cycle, increasing solar activity will result in more opportunities to see auroras in the future. The original story continues below.

On Thursday, October 28, NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory was in the midst of its careful watch over the Sun. Of particular interest to space weather forecasters was a large, volatile sunspot cluster in the southern hemisphere, which they named Active Region 2887 (AR2887).

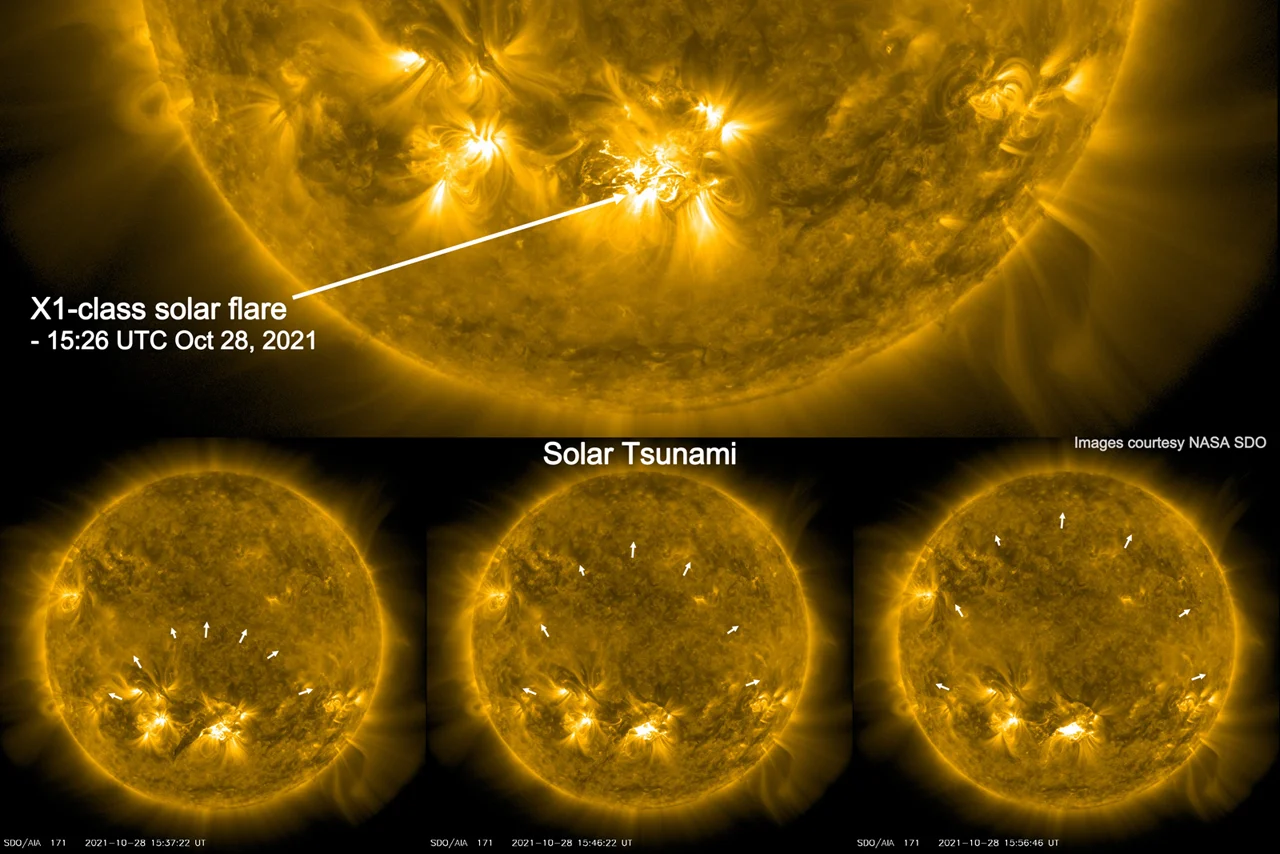

This cluster had been sparking and sputtering with minor and moderate flares for days. Around midday on Thursday, though, it suddenly blasted out an intense X1-class solar flare. The release of energy during the flare set off a 'solar tsunami' — a shockwave that spread out across nearly the entire face of the Sun.

The top panel of this composite image shows a closeup look at the southern hemisphere of the Sun and Active Region 2887, at the moment Thursday's X1 solar flare began. The three panels below track the solar tsunami that immediately radiated out across the Sun's surface over the next 30 minutes. Credit: NASA SDO/Scott Sutherland

Immediately following the flare, the top of Earth's atmosphere was bombarded by intense ultraviolet radiation and solar x-rays.

According to NOAA's Space Weather Prediction Center, this resulted in a strong radio blackout on the day side of Earth. Radio blackouts occur in the aftermath of strong solar flares, as the UV and x-rays from the flare disturb Earth's ionosphere, causing it to degrade or completely absorb high-frequency radio signals. This can completely disrupt radio communications between points on Earth's surface, and between the surface and satellite in orbit. A minor solar radiation storm has also been impacting Earth since the flare, due to solar protons being accelerated away from the flare region.

WATCH FOR THE NORTHERN LIGHTS!

Although the flare, the solar tsunami, and the radio blackout occurred roughly at the same time on Thursday, and the solar radiation storm began a short time after, there's one more impact from this event that we're still waiting for.

In the aftermath of the flare, an immense coronal mass ejection (CME) erupted into space, aimed more or less directly at Earth. A CME, sometimes called a 'solar storm', is a cloud of charged solar particles that can blast away from the Sun during a solar flare.

The initial CME eruption on Thursday was caught by SDO, but it was the NASA/ESA Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) that captured its full scope (as seen in the tweet below).

SOHO has a special camera known as a coronagraph, which blocks out the direct light from the Sun using a small disk positioned in front of the camera lens. This allows the instrument to image the streamers of the solar wind. It can also capture coronal mass ejections as they erupt from the Sun's surface, revealing their size, what direction they are travelling, and even the speed at which they are expanding away from the Sun.

While it only takes around 8 minutes for the light and x-rays from a solar flare to reach us, and solar protons arrive tens of minutes after, it takes CMEs a bit longer to cover the distance between the Sun and Earth. Typically, they pass us a few days after the eruption. CMEs from exceptionally strong flares, however, have taken as little as 16 hours to reach us.

Watch Below: Chris St Clair talks to TWN science writer Scott Sutherland about the Sun, CMEs, geomagnetic storms and the Northern Lights

According to NOAA's Space Weather Prediction Center, based on data from the ACE satellite (in orbit of Lagrange Point 1, between the Earth and the Sun), it appears the CME from Thursday was slower than initially estimated. It finally arrived just after 5 a.m. EDT (around 0900 UTC) on October 31.

In their latest update, NOAA space weather forecasters are now predicting G1 (minor) geomagnetic storm levels starting around midday Sunday (EDT). These are expected to ramp up to G2 (moderate) through the afternoon, and reach G3 (strong) levels Sunday evening (EDT).

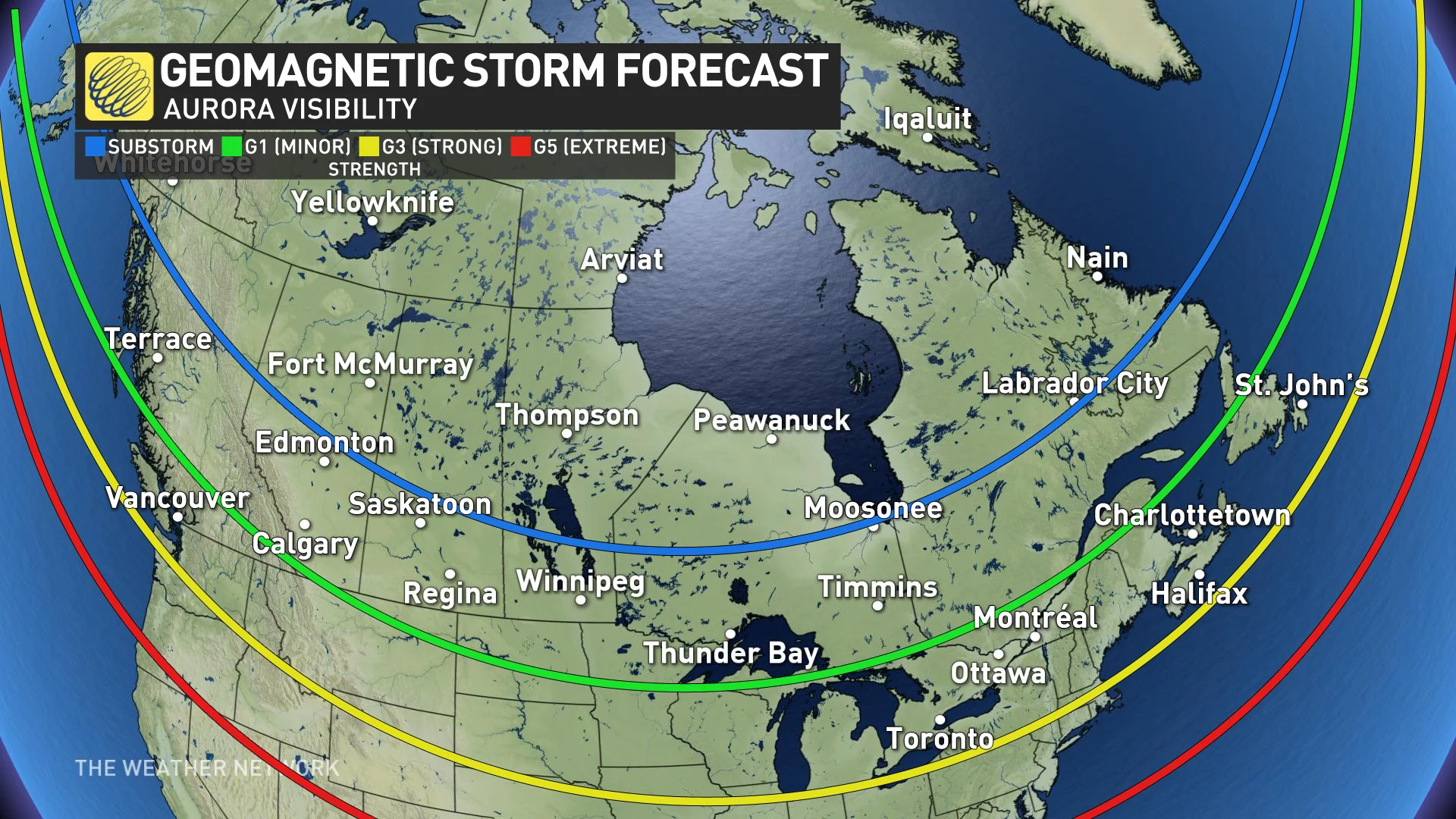

NOAA SWPC ranks geomagnetic storms on a 5-point scale, from G1 (minor) through G5 (extreme). The severity is based on the predicted density, energy, and speed of the CME or solar wind.

Geomagnetic storms are capable of causing issues with power grids here on the ground and they have been known to cause problems with orbiting satellites as well. The probability of seeing these effects goes up with the severity of the storm. Most often, though, the most noticeable impacts of a geomagnetic storm are the vibrant displays of aurorae we call the Northern and Southern Lights.

Auroras can be seen at pretty much any time of year in the far northern regions of Canada. However, during a geomagnetic storm, the arc the auroras follow is pushed southward. The stronger the storm, the farther south the auroras can be seen.

For a G3 geomagnetic storm, the auroras stretch down across all of Canada. They may even be seen from parts of southern Ontario, which are usually too far south to view these displays.

Cloudy conditions will block visibility, of course. Be sure to check your local weather forecast for sky conditions before you head out. Also, even with clear skies, city light pollution makes it very difficult to spot auroras. They may appear very bright and vivid in photographs, but often those images are long-exposure images, and the auroras were only barely visible to the unaided eye. As such, even if you have clear skies, it's best to get away from city lights to view these events.

Read more: For more sights to see in the sky this season, and complete guide on how to get the most out of viewing auroras and meteor showers, see our Fall Night Sky Guide.

Thumbnail image provided by Alberta aurora chasers Tree and Dar Tanner.