The Eta Aquariid meteor shower peaks tonight. Here's how to watch from anywhere!

Under clear, dark skies tonight? Look up to see bits of Halley's Comet streaking through the air!

Comet Halley is probably the most well-known comet in the world, but did you know that each year, it produces two different meteor showers? The first of those, the eta Aquariids, peaks tonight!

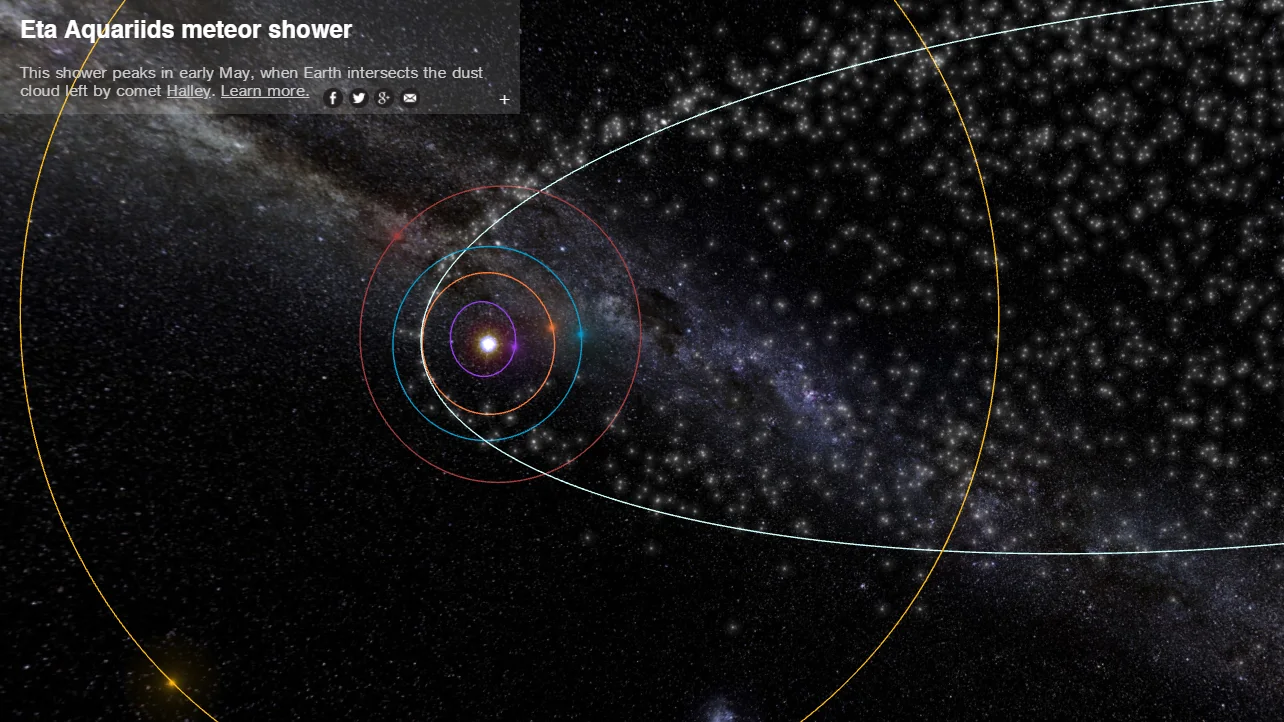

As comets fly through our solar system, they leave behind trails of dust and ice along their path. This is especially true during the time they spend in the inner solar system when they make their periodic pass around the Sun. There are also a few known asteroids that do this. As Earth travels along its orbit, the planet passes through more than two dozen of these trails each year. Each time this happens, it produces a meteor shower in our skies.

This simulation shows the trail of meteoroid debris left behind by comet 1P/Halley on its 75-year journey around the Sun. Earth's orbit is depicted in blue. Credit: Ian Webster/Peter Jenniskens/meteorshowers.org

The eta Aquariids is the first of two annual meteor showers we see due to comet 1P/Halley (more commonly known as Halley's Comet). The meteor shower's name comes from the part of the sky where it appears to originate from, which is near the constellation Aquarius. As the debris stream from the comet is fairly spread out, we can see meteors from this shower on nights between April 19 to May 28 each year.

On the night of May 5-6, though, we reach the most concentrated part of the stream, and thus we see the peak of the meteor shower. The best time to watch the eta Aquariids is in the hours before dawn on May 6, since the shower only begins around 2:30 to 3:00 a.m. local time.

The eta Aquariids typically produce around 50 meteors per hour. Since the meteors vary in brightness and most flash by in less than a second, most observers report seeing about half that total number.

The radiant of the eta Aquariid meteor shower, in the hours before dawn, on May 6. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

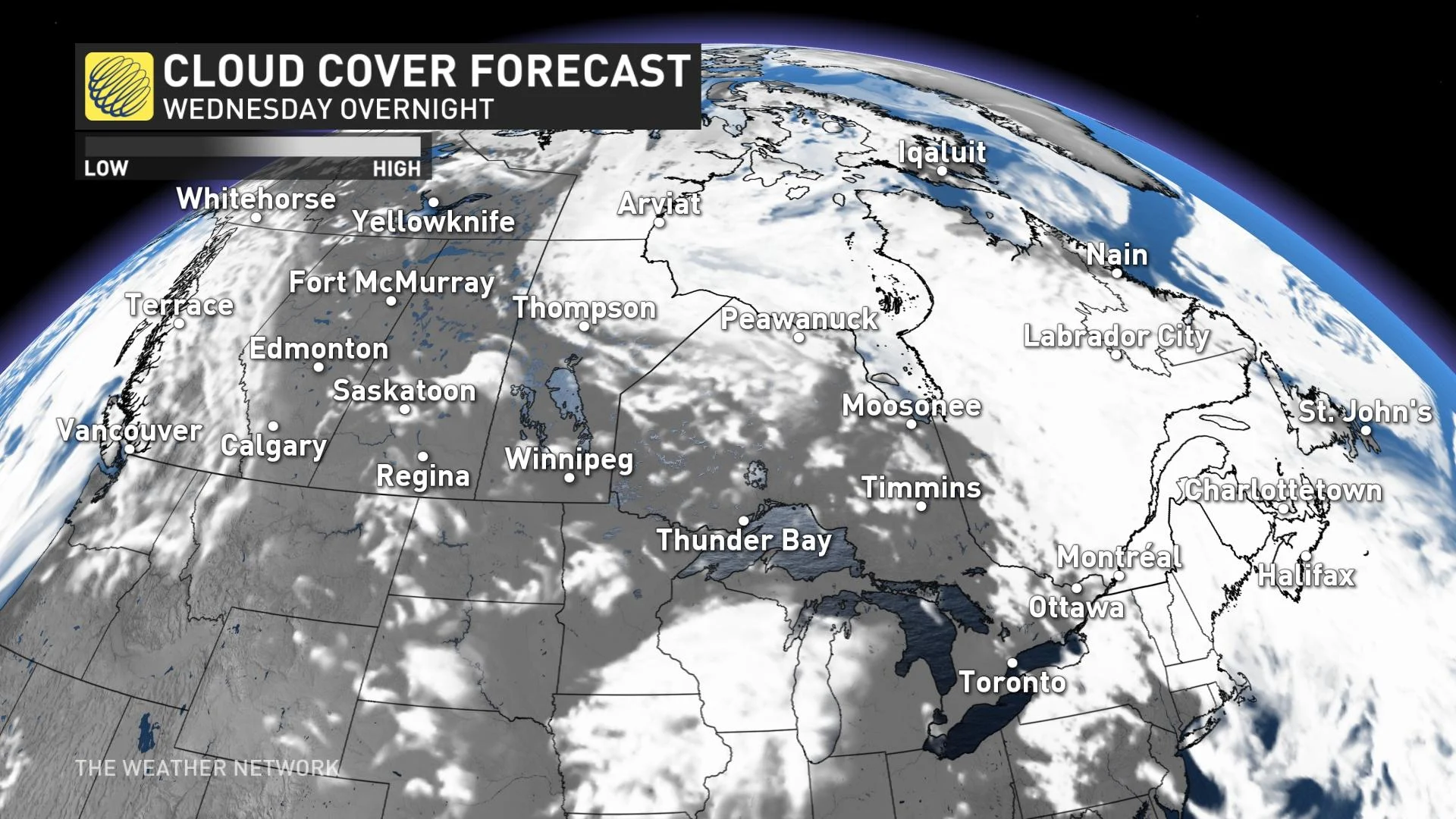

WILL WE SEE IT?

Since clear skies are essential for watching meteor showers, check your forecast and the map below to see if your view will be reasonably free of clouds. Also, be sure to read on below for tips on meteor watching.

If it is cloudy where you are, there are other ways to 'watch' meteor showers, right from your computer at home.

When meteoroids plunge into the atmosphere, they produce tiny disturbances that can be picked up by radar. The Meteorscan website streams a constant live feed of these radar detections, which show up as multicoloured spikes. The bigger the spike, the bigger the meteoroid, and the brighter the meteor. We can also listen via the Meteor Echoes Livestream, which presents these disturbances as quick pings (and it can also pick up passing satellites from time to time).

Astronomy Live Stream also streams nightly views of the sky over Colorado. Watch below to see one meteor (in the top-right quadrant of the view) captured on the night of May 4-5, 2021.

Related: Got your hands on a space rock? Here's how to know for sure

PERSISTENT TRAINS

Unlike the Lyrids, which peaked a few weeks ago, this meteor shower does not tend to produce bright fireballs. The meteoroids are moving so quickly when they hit our atmosphere, however, that they can produce a phenomenon called persistent trains.

Watch below to see a persistent train from a Geminid meteor

When a typical cometary meteoroid hits the top of Earth's atmosphere, it moves fast enough to produce a meteor flash (as mentioned above). Eta Aquariid meteoroids hit Earth's atmosphere, travelling nearly two and a half times as fast, though!

Streaking through the air at 240,000 km/h, Comet Halley meteoroids produce the usual brief meteor flash, but they can also result in a bonus. Once the meteor goes out, a glowing trail is left behind, floating in the air, called a persistent train. Some persistent trains last for minutes after the meteor flash, while others can remain visible for hours.

Since persistent trains have only rarely been recorded, scientists still aren't quite sure what causes them. There are two possible explanations, though.

The first is that the meteoroids are travelling fast enough to strip electrons from the air molecules, leaving them in an ionized state. As the air molecules snatch up electrons from their surroundings, they release energy in the form of light. Since this process can take much longer than the original meteor flash, the 'train' appears fainter, and it can persist for some time after the meteor flash ends.

The other idea involves what is known as 'chemiluminescence'. Metals vaporizing off the fast-moving meteoroid's surface can chemically react with ozone and oxygen in the air to produce a glow.

One of these explanations may account for trains, or both may cover different occurrences at different times and even between individual meteors. It will take more sightings of these to explain them fully.

METEOR? METEOROID? METEORITE?

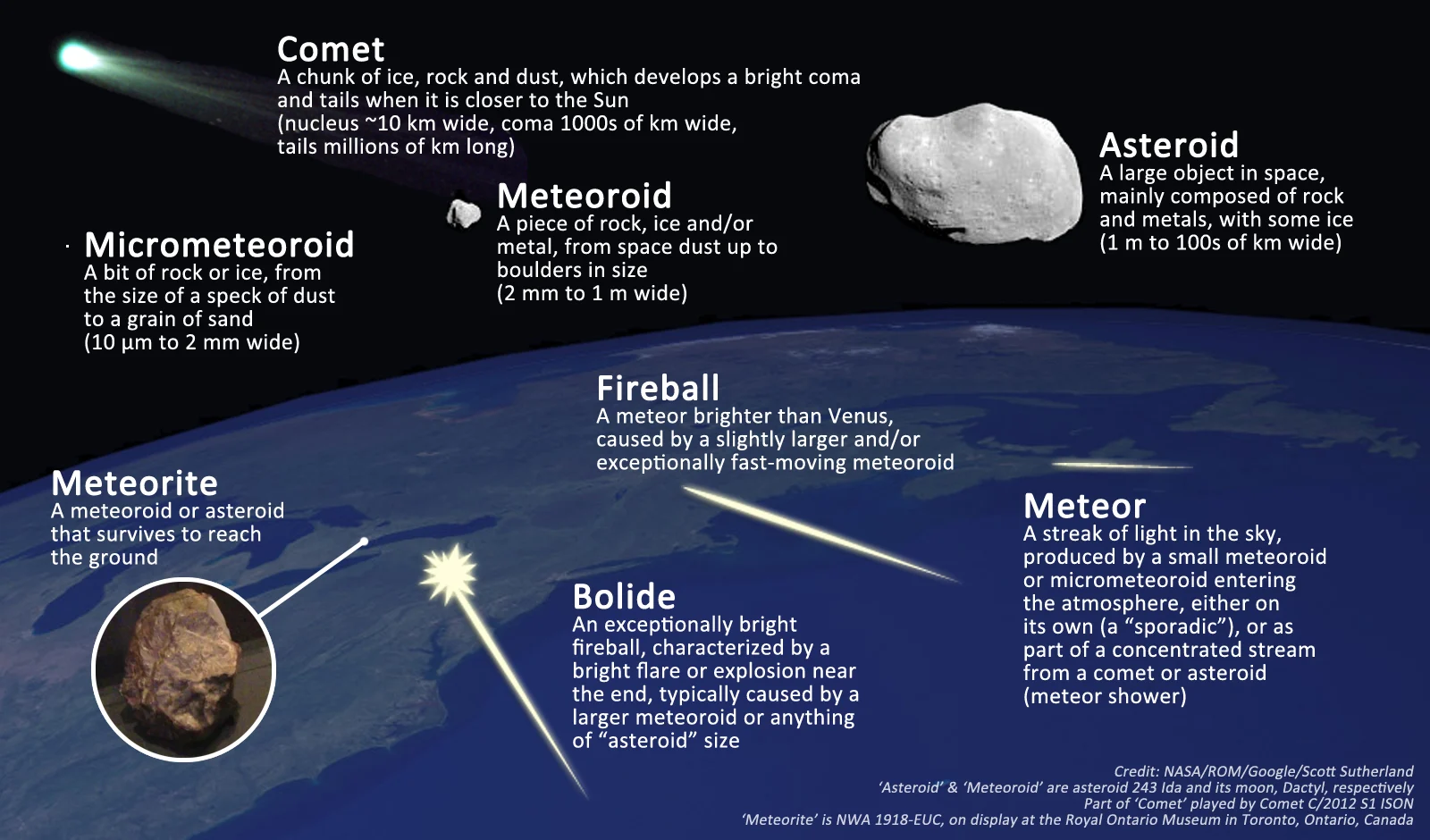

The bright streaks we see during this event are known as meteors. Each occurs due to a meteoroid plunging through Earth's upper atmosphere.

Meteoroids travel at incredible speeds through the atmosphere, ranging between 11-71 km/s. As they do, they compress the air in their path, causing that air to glow white-hot. A typical meteor flash tends to last a second or less, and it is caused by a tiny speck of dust or ice. In general, the larger and faster a meteoroid is, the brighter the meteor from it will be. Larger meteoroids tend to cause longer-lasting meteors, as well, but this can depend greatly on the angle of the object's plunge into the atmosphere.

These brighter meteors are called fireballs, and if it explodes, it is often referred to as a bolide.

Regardless of how bright it is, a meteor 'winks out' when the meteoroid vaporizes or when it slows down enough so that it can no longer compress the air to the point where it glows. Once this happens, any part of the meteoroid that survives enters what's known as 'dark flight'. It basically becomes a rock falling from the sky, and if we find these rocks on the ground, we call them meteorites.

Related: Want to find a meteorite? Expert Geoff Notkin tells us how!

TIPS FOR METEOR WATCHING

First, some honest truth: Many people who want to watch a meteor shower end up missing out on the experience. Follow this guide to get the most out of these events.

Here are the three 'best practices' for watching meteor showers:

Check the weather,

Get away from light pollution, and

Be patient.

Clear skies are very important for meteor spotting. Even a few hours of cloudy skies can ruin an attempt to see a meteor shower. So, be sure to check The Weather Network on TV, on our website, or from our app, and look for my articles on our Space News page, just to be sure that you have the most up-to-date sky forecast.

Next, you need to get away from city light pollution. If you look up into the sky, are the only bright lights you see street lights or signs, the Moon, maybe a planet or two, and passing airliners? If so, your sky is just not dark enough for you to see any meteors. You might catch a bright fireball, but there's no guarantee, and those are typically few and far between. So, get out of the city, and the farther away you can get, the better!

Watch: What light pollution is doing to city views of the Milky Way

For most regions of Canada, getting out from under light pollution is simply a matter of driving outside of your city, town or village until a multitude of stars is visible above your head. In some areas, especially southwestern and central Ontario and along the St. Lawrence River, the concentration of light pollution is too high. Getting far enough outside of one city to escape its light pollution tends to put you under the light pollution dome of the next city over.

In these areas of concentrated light pollution, there are dark sky preserves. However, a skywatcher's best bet for dark skies is usually to drive north and seek out the various Ontario provincial parks or Quebec provincial parks. Even if you're confined to the parking lot after hours, these are usually excellent locations from which to watch (and you don't run the risk of trespassing on someone's property).

Sometimes, based on the timing, the Moon is also a source of light pollution, and it can wash out all but the brightest meteors. We can't get away from the Moon, so we can just make do as best we can in these situations.

Once you've verified you have clear skies and you've gotten away from light pollution, this is where having patience comes in.

For best viewing, you must give your eyes time to adapt to the dark. Give yourself at least 20 minutes, but the longer, the better. Warning: if you skip this step — even if you follow the rest of this guide — you will miss out on a lot of the action.

This Perseid meteor was captured on August 11, 2019, from Lockeport, Nova Scotia. Credit: Barry Burgess/UGC

During this adjustment time, avoid all bright light sources - overhead lights, car headlights and interior lights, and cellphone and tablet screens. Any exposure to bright light during this period will cancel out some or all the progress you've made, forcing you to start over. Shield your eyes from light sources. If you need to use your cellphone during this time, set the display to reduce the amount of blue light it gives off and reduce the screen's brightness as much as possible. It may also be worth finding an app that puts your phone into 'night mode' to shift the screen colours into the red end of the light spectrum, which has less of an impact on your night vision.

You can certainly look up into the starry sky while you are letting your eyes adjust. You may even see a few brighter meteors as your eyes become accustomed to the dark. If the Moon is shining brightly, turn so that it is out of your personal field of view.

Once you're all set, just look straight up!