Here's why NASA sent a clutch of tiny baby squid into space this month

The experiment will study how the tiny animals' relationship with certain kinds of symbiotic behaviour changes in zero-G.

B-grade sci-fi films might sometimes feature tentacled extraterrestrial visitors, but the tentacled beings currently orbiting the planet have a completely mundane Earth-bound origin – not to mention being tiny.

Among the many experiments aboard a SpaceX rocket launched toward the International Space Station earlier this month was a cluster of baby bobtail squid from Hawaii.

Their specific role will be to help researchers examine how their typically symbiotic relationship with the bacterium Vibrio fischeri changes in zero gravity. The hatchlings were set to be exposed to the bacterium after launch.

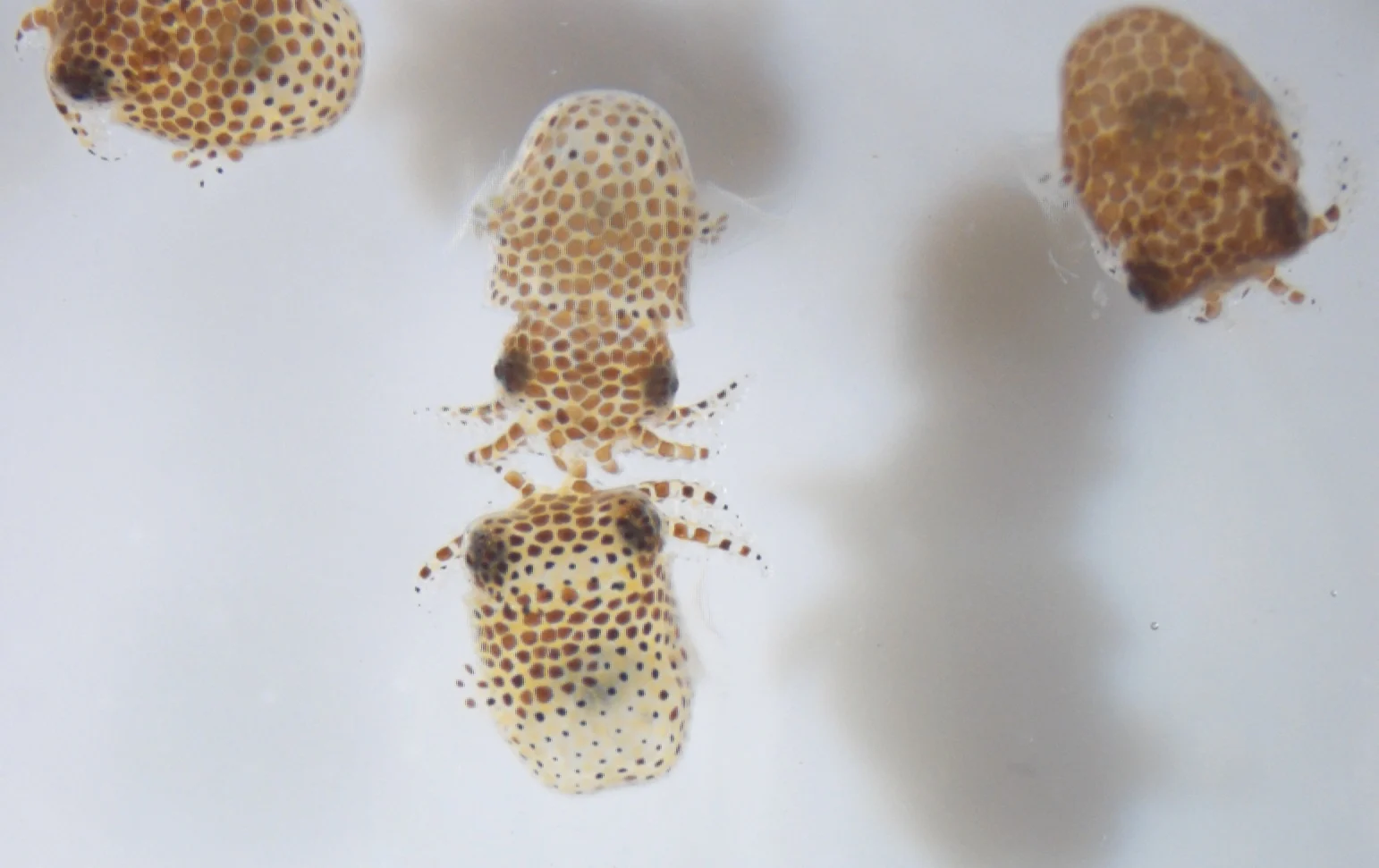

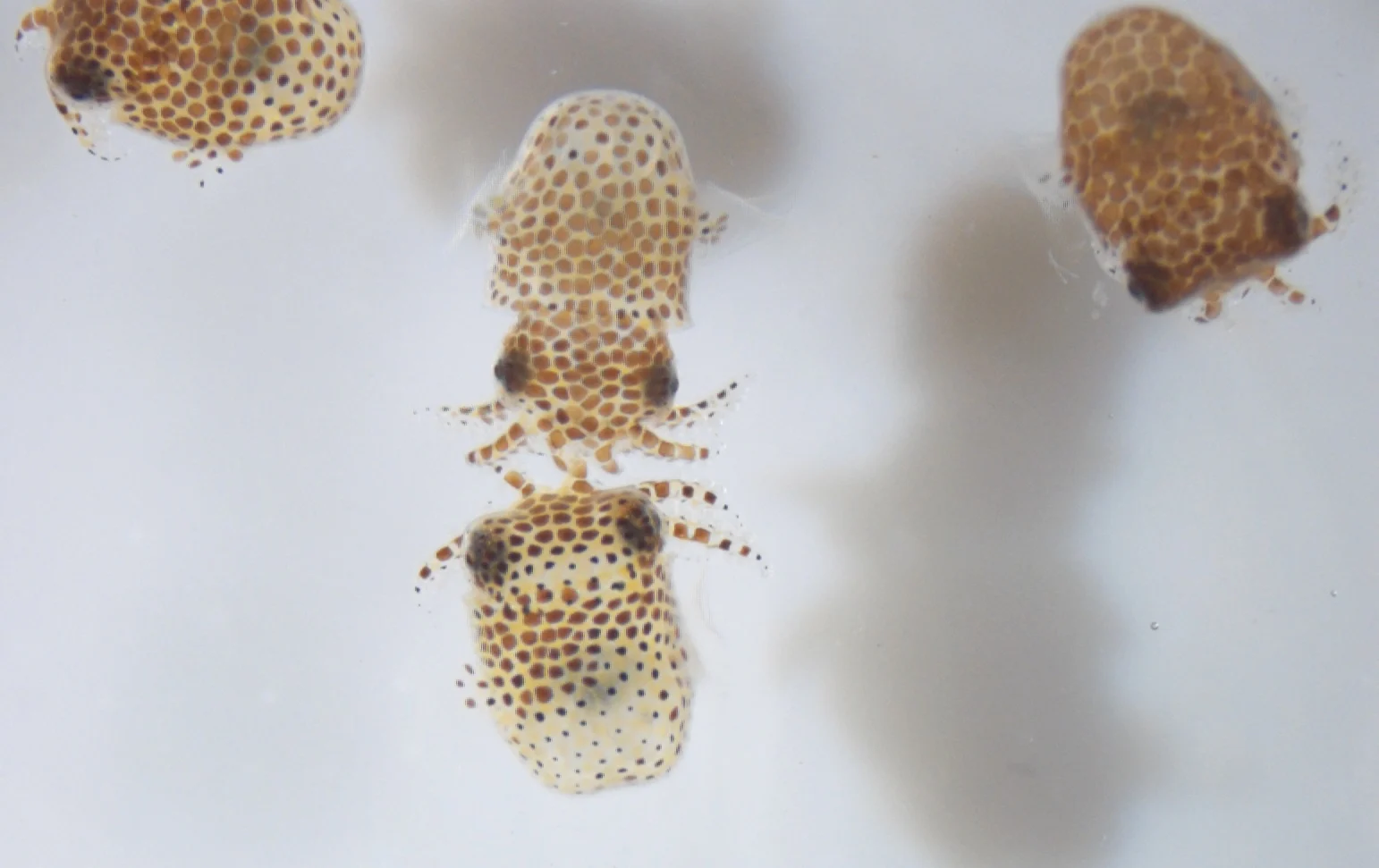

These immature bobtail squid (Euprymna scolopes) were launched to the International Space Station as part of an experiment to see how being in space alters their symbiotic relationship with the bacterium Vibrio fischeri. (Jamie S. Foster, University of Florida/NASA)

How that relationship unfolds in zero-G will have implications for humans, hopefully closing the gap in understanding of those kinds of biological interactions.

"There are more than 2000 identified bacterial species that form associations with humans but are fewer than 100 species identified as human pathogens; yet most microgravity studies have focused on pathogens," the researchers write. "This leaves a large array of undescribed beneficial microbes that form interactions with animal cells which may or may not be impacted by microgravity conditions."

Sending the squid into space isn't beyond the pale for NASA, which has a long track record of including animals of all kinds on a wide variety of missions, including spiders, roundworms, mice, and famously indestructible tardigrades – microscopic creatures known for being able to survive exposure to the vacuum of space.

In fact, this month's mission included a contingent of tardigrades, also known as water bears, which hoped to identify the genes involved in the creatures' hardiness.