Endangered plant found only in N.W.T. 'doing nicely': Recent survey

Seeds from an endangered plant that's found only in the N.W.T. were sent to a seed bank in the U.K. last week to give the rare species a sort of life-raft, if it ever needs it.

But a researcher who collected hairy braya seeds on a remote coast northeast of Tuktoyaktuk, N.W.T., last summer says the field survey left her feeling more confident in the plant's ability to survive. The plant's population estimates have doubled after it was found to be growing in several more sites.

SEE ALSO: Earth's tree of life expands after 146 species discovered in 2022

"When we started to … find all of those plants growing inland, I think we felt better about the future of the species," said Joanna Wilson, a wildlife biologist with the N.W.T.'s environment and natural resources department.

Also known as the braya pilosa, the hairy braya is a flowering plant in the mustard family that is listed as threatened in the N.W.T. and endangered in Canada.

The hairy braya's main threat, said Wilson, is erosion — which is a pressing problem, because the plant is only known to grow in the coastal area of Cape Bathurst and the nearby Baillie Island on Inuvialuit private lands.

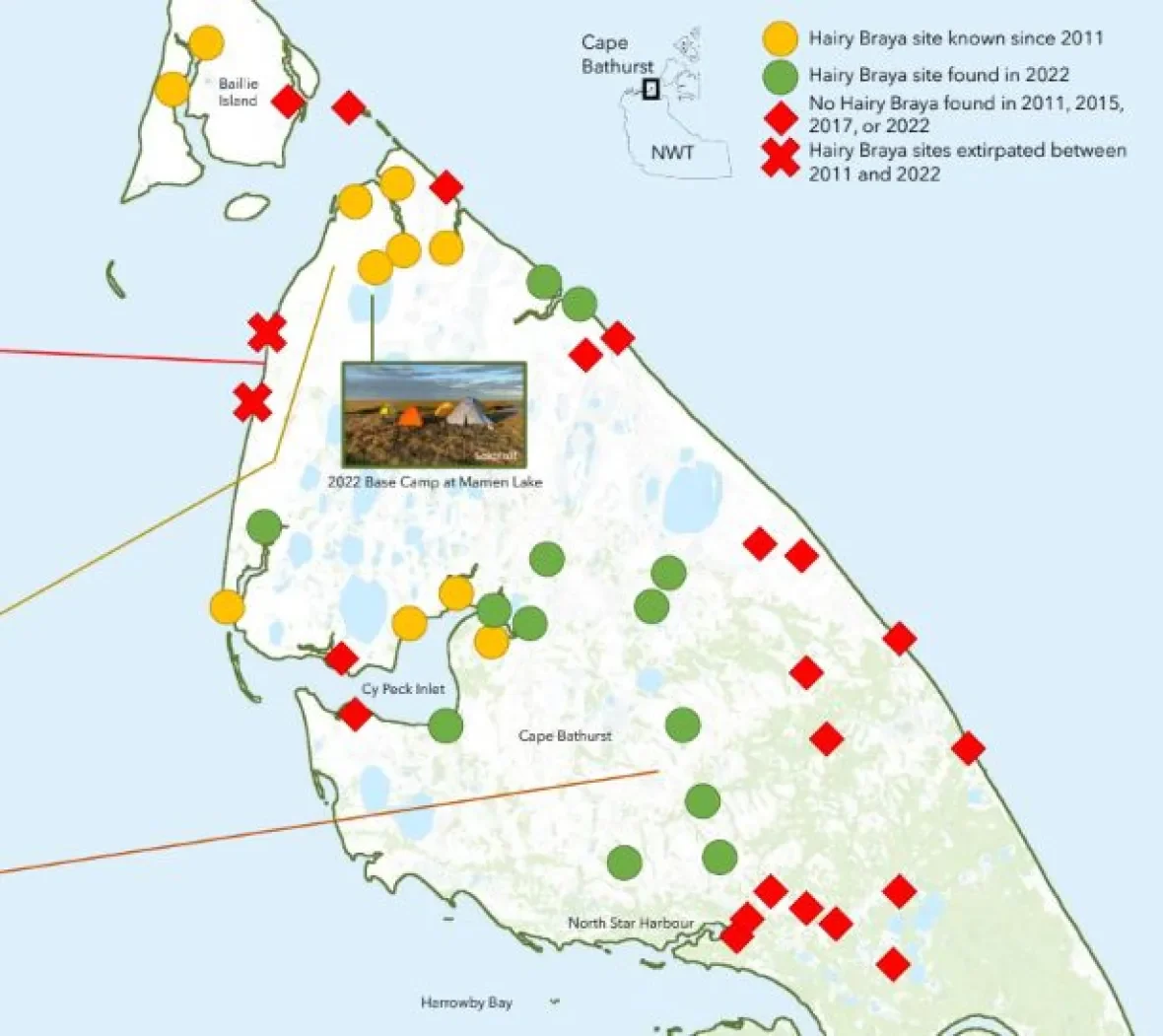

The survey showed two sites where the plant was growing before — on the west coast of Cape Bathurst — have completely eroded away in the last decade, said Wilson.

A hairy braya field survey in August 2022 included 5 days of combing the Cape Bathurst landscape on foot, and 4 days using a helicopter. (Joanna Wilson)

But after spending five days on foot and four days in a helicopter searching for the plant, Wilson said she was happy to discover the hairy braya's range extended further south than previously thought.

"Most of the plants are growing away from the coast, so they're not subject to that really obvious threat. They're more secure," she said.

Now growing in 19 sites

Jim Harris describes the hairy braya as the highlight of his botanical career. It was the subject of his PhD in the early 1980s, and during a field survey on Cape Bathurst in 2004 he discovered the species had not gone extinct.

Harris has since retired from teaching botany at Utah Valley University, and was part of the small team that headed to Cape Bathurst last year — his third time seeing the plant in its natural habitat.

A hairy braya plant on Cape Bathurst in the N.W.T. in 2022. The rare species is vulnerable to coastal erosion and salty spray from the sea. (Jim Harris)

The 2022 survey established the hairy braya is growing in 19 sites. Harris confidently estimates the population has at least doubled to between 25,000 and 50,000 plants.

"To be able to rediscover the plant and then from there, learn that it's actually been doing quite nicely for the last couple hundred years in its home there on Cape Bathurst, it's just really been interesting and exciting to me," he said.

What we don't know

There's a lot that remains a mystery about this small little mustard plant. For example, why is it only found in a small part of the N.W.T.?

"Cape Bathurst, large portions of it at least, were apparently not glaciated during the Pleistocene [Ice Age] and so it appears that the plant survived in kind of a little refuge there," said Harris.

He said it's a "bit odd" it hasn't spread much, because most other types of braya expand easily across Arctic and alpine habitats.

A map of locations where the hairy braya has been found during field surveys. Thirteen new sites were found during the 2022 trip, but some were in close proximity to other locations — which is why there are now considered to be 19 sites on Cape Bathurst and Baillie Island where it is growing. (Submitted by Joanna Wilson)

Wilson said the hairy braya is eaten by some critters, but researchers don't know which ones. They also suspect muskox and caribou disturb the soil on the coast with their hooves in such a way that it creates or maintains the type of conditions the plant needs — but Wilson said that's just an observation that hasn't been studied yet.

"The more muskox we see, the more hairy braya we find," said Floyd Dillon, a man from Tuktoyaktuk who was hired as a wildlife monitor for the trip and who was trained to identify the plant as well.

Dillon hadn't heard of the hairy braya prior to the survey and said it didn't have a meaning he was aware of in Inuvialuit culture.

A caribou travels on Cape Bathurst in the N.W.T. Joanna Wilson, a wildlife biologist for the territory, says caribou and muskox hooves appear to churn the region's soil in a favourable way for the hairy braya to grow — but that it's just an observation researchers have made so far. (Jim Harris)

The value of a life-raft

Wilson said it's important to protect species like the hairy braya because they contribute to the territory's biodiversity.

"When we start to lose parts of that …we're worse off," she said, adding that intact ecosystems — with undamaged webs of animals, plants and microorganisms — are more resilient to threats.

A hairy braya plant clings to the edge of a bluff, where the soil is eroding. A root connecting two parts of the plant is exposed. (Joanna Wilson)

Sending twenty packets of hairy braya seeds to the Millennium Seed Bank in England was part of the territory's recovery strategy for the endangered hairy braya. The seed bank has a mandate to protect wild species, particularly ones that grow in small areas or are threatened by climate change, said Wilson.

The work she and her team did will also help the N.W.T. assess the hairy braya's threatened classification in 2024 — which is something that is revisited every ten years.

WATCH: How the evolution of land plants helped to shape Earth

Thumbnail courtesy of Jim Harris.

The story, written by Liny Lamberink, was originally published for CBC News.