Digging into the drought: Why one massive Prairie rainstorm doesn't help

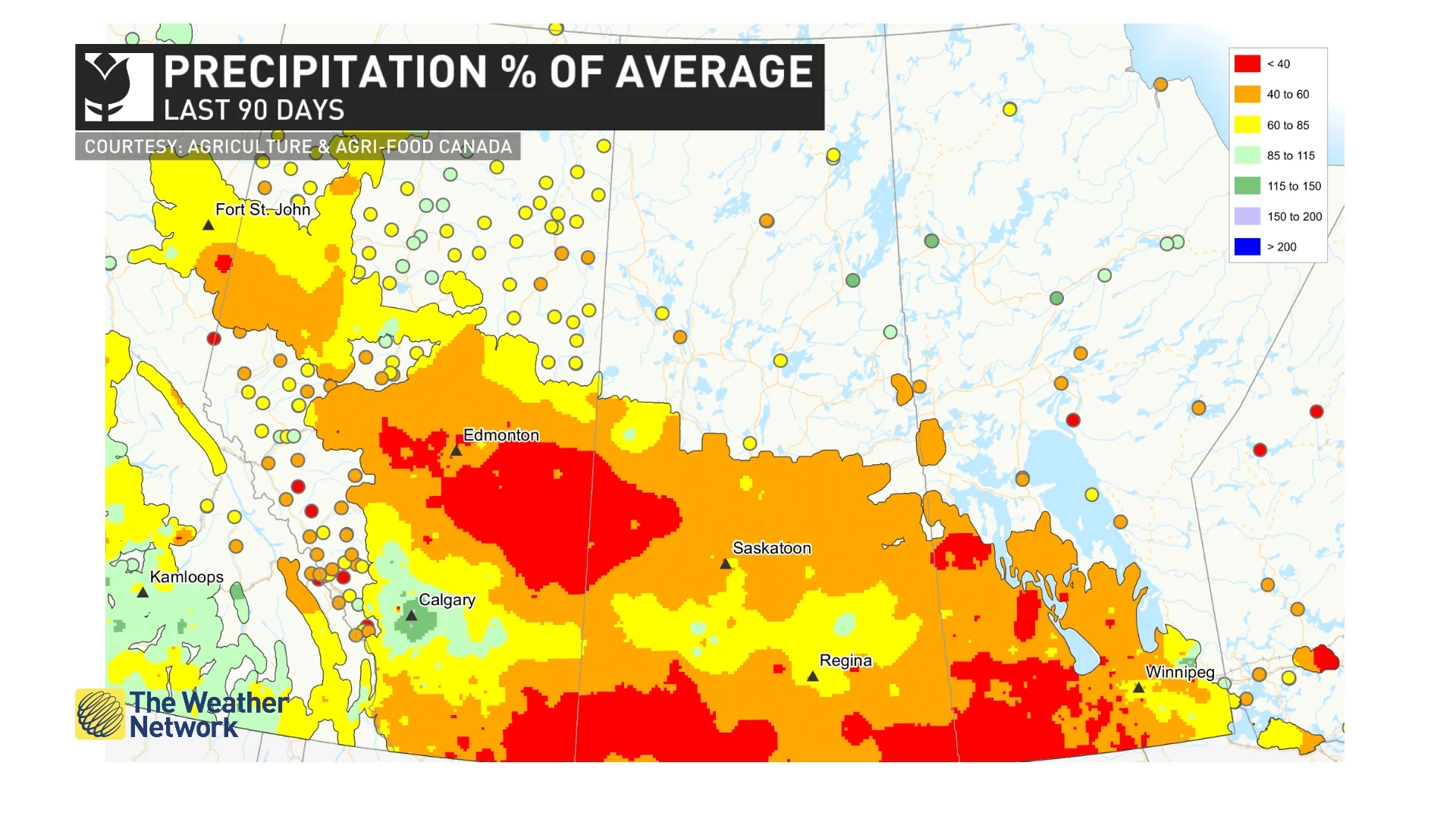

Much of the Prairie region has received below-average precipitation over the past three months.

Precipitation, of all kinds, is the lifeblood of the Prairies, but the region’s wellbeing relies on a delicate balance – too much, and too little, are both consistent concerns.

The need for precipitation exists year-round, even outside the actual growing season. Winter snow is needed to ensure plenty of soil moisture and full reservoirs to kick things off in the spring, while welcome summer rains top up reserves and ease the burden on irrigation systems.

This past winter, however, the snows haven’t held up their end of that bargain. Around 80 per cent of the Canadian Prairie have received less than half their seasonal average rainfall.

While a less voluminous snowpack means somewhat drier soil in the spring – a boon for farmers hoping for early access to their fields – there’s less moisture on hand as the spring turns to summer, with its hotter and drier days set to strain water supplies.

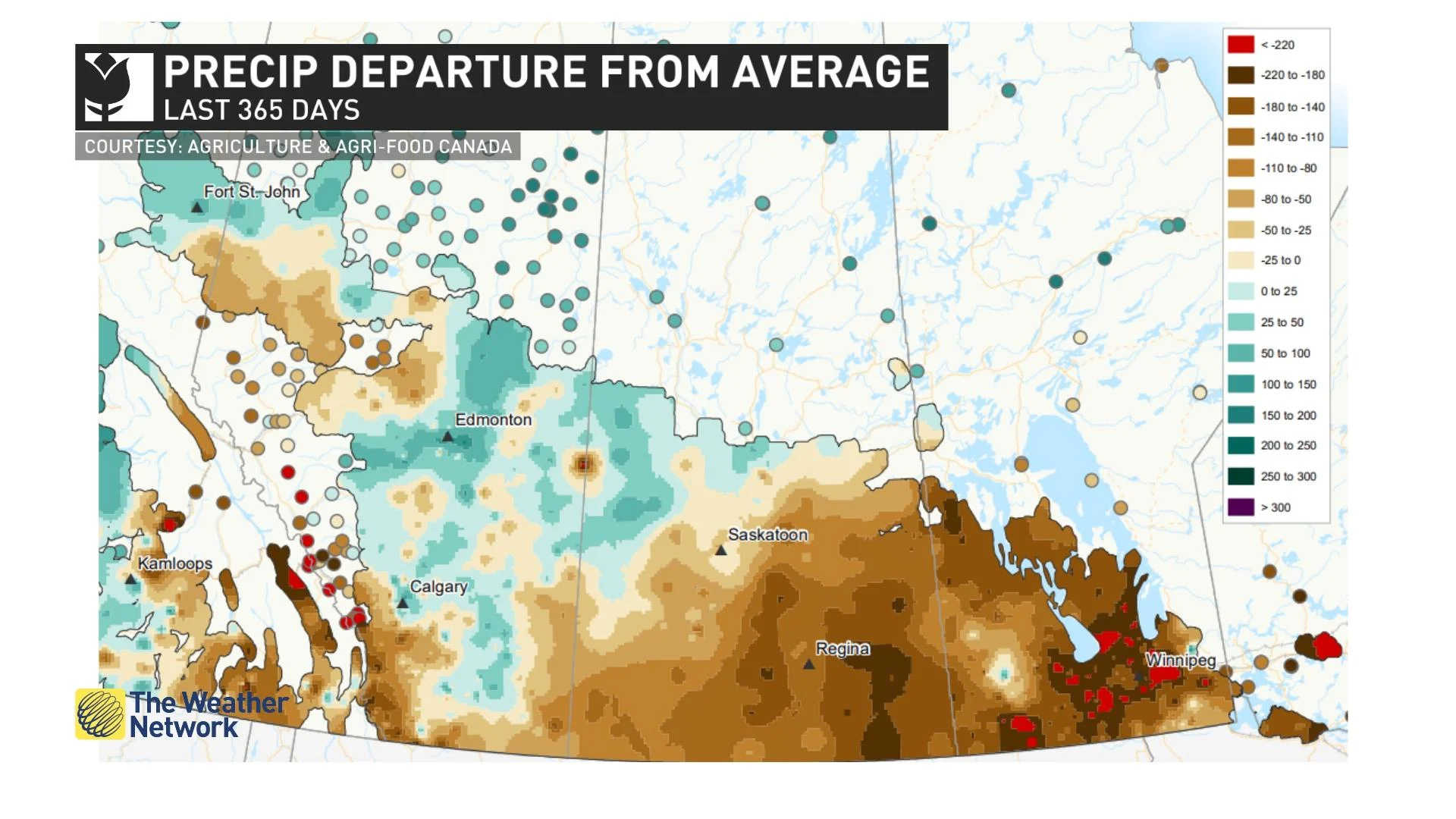

And prior to the winter, it was a mixed bag across the region. Over the past 12 months, the western Prairies saw above-average precipitation, while areas from roughly Regina and eastward to northern Ontario were below by 100-200 mm depending on location.

But there’s one glaring outlier that is a good example of how getting an enormous amount of precipitation all at once is not as preferable as having it spread out more consistently: Brandon, Man., which unlike the rest of the eastern Prairies saw above-average precipitation.

What could be behind this?

Digging into the data, we can find records of a single storm that dropped an astounding 155 mm of rain on June 28th last year in a 10-hour window, nearly double the monthly average and 30 per cent of all precipitation over the last year.

However, that doesn’t mean Brandon escaped the drought conditions. Normally, the Prairie region’s summer precipitation comes from convective and frontal thunderstorms from June to August. Ideally, they don’t become severe, avoiding damaging hail and flooding rain, instead providing manageable pulses of moisture.

Brandon’s deluge, however, was simply too much water. In such cases, flash flooding can occur when heavy rain falls on very dry soil, forcing the bulk of the water into drainage systems, so the soil only really benefits from a small portion of it, whether directly or through reservoirs, which themselves wouldn’t have snagged 100 per cent of it.

Flash flooding can occur when heavy rain falls on very dry soil, acting more like concrete. This forces the water to run down the drainage system, bypassing the parched soil. Yes, a portion of the rainfall was snatched up by the farmland and reservoirs but not 100% of it.

So, no, Brandon didn’t escape its drought. Seasonal precipitation timing, event duration, temperature, and crop status all play an additional role when analyzing the significance of a drought, and that single deluge wasn’t enough for farmers.

With files from Daniel Martins.