Four terrifying disasters waiting to happen

Digital Reporter

Monday, March 21, 2016, 8:30 AM - To step out the door of your house is to invite some measure of risk.

It's not that the gods have it in for you. It's just a question of location, probability, time of year, and lots of other things that factor into the chances of some hassle befalling you.

This article, though, isn't about a car collision, or your computer at work going on the fritz, or slipping on an icy sidewalk. This is about the kind of catastrophe that can put a serious dent in your civilization.

We took a look at four terrifying disasters just waiting to happen.

The supervolcano lurking beneath Yellowstone

Image credit: Jim Peaco/National Park Service/Wikimedia Commons

When someone says "Yellowstone National Park," three things come to mind: The colourful Grand Prismatic Spring (up above), the geyser at Old Faithful, and the terrifying possibility of an erupting supervolcano.

The park sits on a large magma chamber, part of a supervolcano that has, in the past, belched out around 1,000 cubic kilometres of ash in one of several eruptions, enough to fill Lake Erie twice over. The last time an eruption that powerful happened, about 640,000 years ago, it carved the 55 by 80-kilometre Yellowstone Caldera out of the Earth.

Since then, it's experienced around two dozen smaller eruptions, though the last one about 70,000 years ago, long before the peopling of the Americas.

Image source: Wikimedia Commons

If another major eruption happens, however, expect some serious blowback, literally and figuratively.

A recent study found that if the supervolcano does erupt, it'll toss enough ash into the atmosphere to bury nearby cities up to a metre deep, with a dusting of a few millimetres in cities on the coasts, hundreds and thousands of kilometres away.

And many of the aerosols emitted by the volcano will linger in the atmosphere, dimming the sky and lowering global average temperatures by just enough to impact the climate.

So when can we expect this catastrophe? Despite the occasional dire warning you see in some media, volcanoes don't exactly run on a set schedule, so the truth is it likely won't happen for quite some time.

Image: Daisy Geyser, Yellowstone National Park, by Brocken Inaglory/Wikimedia Commons

A recent study that found a massive reservoir of hot rock, with a similar volume to the Grand Canyon, beneath the magma chamber, calculated a "repeat time" for a caldera explosion of around 700,000 years, according to the Washington Post.

Earthsky reports another study put the risk at one or two million years in the future, while still another study, reported in the International Business Times, was about 99.9 per cent certain it wouldn't happen in the 21st Century.

Such an eruption could cause economic and climatic devastation on a global scale. Just don't lose too much sleep over it just yet.

Africa's deadly, exploding lakes

Lakeside living is an attractive prospect for many -- provided you’re not beside the kind of lake that can kill you, and everyone you know, without warning.

That’s what happened in the West African country of Cameroon in 1986, around the shores of Lake Nyos. It was the site of an exceedingly rare event known as a limnic eruption, the result of a long buildup of dissolved CO2 due to nearby volcanic activity.

Image: Wikimedia Commons/Frédéric Mahé

In most cases, lakes in volcanically active areas divest themselves of harmful gases due to regular turnover of the water. But Nyos, nestled in a 400-year-old volcanic crater, was unusually still, according to Atlas Obscura. So with nothing to help disperse it, the CO2 just kept accumulating, until an as-yet unknown trigger caused it to blow.

The force of the blast set off a small tsunami and tossed a plume of water hundreds of metres into the air, but it was the emitted gas, about 1.2 million cubic kilometres’ worth, that was the real killer.

Though many escaped to higher ground, more than 1,700 people were killed, suffocated by the gas, some as much as 25 km inland. Whole villages were all but wiped out, along with around 3,500 livestock. And after the eruption, the roiling waters brought iron deposits to the surface, making the lake appear blood red.

French scientists moved to prevent it from happening again by running a 200 m pipe down into the lake’s depths. The CO2-rich water fizzes upward like a pop in a shaken bottle, dispersing the gas when it spouts outward on the surface.

Image: USGS/Bill Evans

But they’ll need a lot more pipes to take the pressure off of Lake Kivu, a much larger lake between Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo that is believed to have some 60 billion cubic metres of methane dissolved within it.

Two million people live on and around the lakeshore, and even without a full-scale eruption, CO2 vents claim lives every now and again.

But necessity and entrepreneurship may have a solution. The methane of the lakewater is a potential source of energy, and in recent years, pilot projects have sprung up to extract it, and CO2, for use in local power plants.

According to the Guardian, extracted methane from the lake met around four per cent of Rwanda’s power needs in 2010, with plenty of room to grow.

Image: Wikimedia Commons/David Stanley

Giant space rocks hitting the Earth

Everyone knows about the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs, but even an asteroid that’s too small to cause a mass extinction can do bad things to Earth’s present-day climate.

One study published in early 2016 took a look at what would happen if an asteroid one kilometre in diameter were to make a direct hit on our planet.

The results were sobering. Aside from gouging a 15-kilometre crater into the surface (And annihilating any towns and infrastructure that might have been at ground zero), the dust it would kick up would stay in the air for six years, according to the worst-case scenario. If it fell in a forested area, the soot from the wildfires would take a decade to disperse.

The impact would be twofold, according to Discovery News. First, particles suspended in the stratosphere would heat up, speeding a chemical reaction that would temporarily strip 55 per cent of Earth’s ozone layer, more than halving our protection from harmful UV radiation.

Image: NASA/JPL/Wikimedia Commons

Second, the extra particles in the atmosphere could block up to 70 per cent of sunlight in the first couple of years. That’ll be the true catastrophe: Global average temperatures could drop by 8oC, plunging us into an ice age. Precipitation could drop by 50 per cent, wrecking agriculture. It would be a global catastrophe.

If it hit the ocean, the climate impact would be somewhat less (aside from a destructive tsunami), but salt water vapour could harm the ozone layer to an even worse degree, such that UV radiation would be even worse for the first year before recovering.

How likely is this to happen? The answer to that is both reassuring and worrying.

NASA says it knows of nearly 900 near-Earth asteroids that are kilometre-sized or larger, which models suggest is around 90 per cent of the total, according to Discovery News. A report by Wired suggests there’s a 0.01 per cent chance one of these rocks will hit the Earth in the near future.

Problem: Those are just the ones NASA knows about, and an asteroid doesn’t need to be the size of a mountain to cause massive devastation.

Wired says, out of about a million asteroids large enough to cause a catastropically powerful Tunguska-level event (more on that in a bit), only around 10,000 are tracked.

The aforementioned Tunguska event involved an asteroid NASA says was only 36 metres across when it exploded over the Siberian wilderness in 1908, with the force of up to 20 megatons of TNT. The blast was powerful enough to knock people down dozens of kilometres away, and toppled an estimated 80 million trees. Those believed to have been directly below the blast were stripped of their limbs, like a forest of telephone poles, according to the Soviet researchers who visited the site.

And as for the present day, remember the Chelyabinsk meteor?

When that rock exploded over the Russian town of the same name, it injured more than 1,500 people, burned skin and retinas and damaged more than a thousand buildings. The blast was rated at around 500 kilotons of TNT.

And remember, nobody had any idea the asteroid was in the neighbourhood: All eyes at the time were on another, totally unrelated asteroid, 2012 DA14, which passed near the Earth at around the same time as the Chelyabinsk meteor.

This doesn’t mean something like that will happen tomorrow, just that there’s still plenty of night sky that needs watching, and not enough eyes to watch it.

An unbelievably powerful earthquake is brewing off the B.C. coast

To anyone standing right next to one, an earthquake of Magnitude 9.0 or greater is what the end of the world looks like.

They’re exceedingly rare, and incredibly destructive. The 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake, which may have been as strong as M9.3, sparked a tsunami that killed more than 200,000 people. The Magnitude 9.0 Tohoku quake in Japan claimed 16,000 lives and triggered a nuclear meltdown.

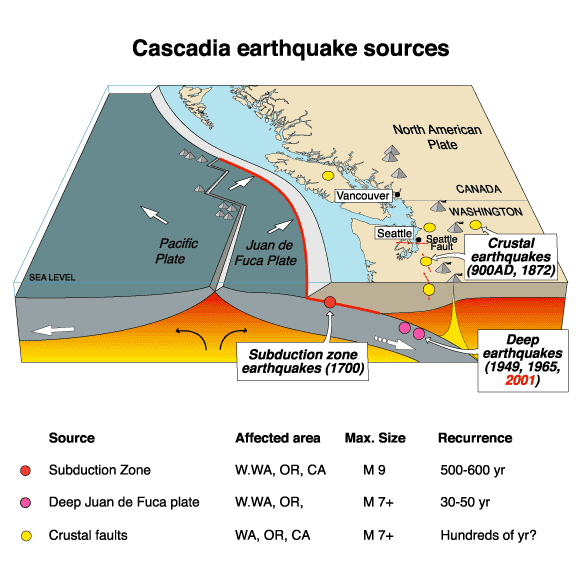

Most quakes of that strength are “megathrust” quakes. And there’s almost certainly one brewing near British Columbia and the U.S. Pacific Northwest.

Image: USGS/Wikimedia Commons

Offshore of that region, the Juan da Fuca plate is slipping slowly beneath the North American plate. And part of the plate has been “stuck” for quite some time, with the pressure building and building. When it finally jerks forward, the result will be a destructive earthquake, right on Vancouver’s doorstep.

CBC reports there’s around a 1 in 100,000 chance a Magnitude 9.0 earthquake can happen on a given day. The City of Vancouver puts the odds of an offshore quake at 1 in 40 over the next 50 years, though there’s also a chance of a smaller, but just as damaging quake in the Georgia Strait (a shallow M7.3) or beneath the Coastal Mountains (a deep M6.3).

"When it [happens], we can expect damaged buildings and infrastructure, flooding, fires, and thousands of people forced from their homes,” the city says on its earthquake preparedness website. “Our transportation systems will be disrupted, and there will likely be interruptions in our electricity and telecommunications systems, too."

The Insurance Bureau of Canada says an M9.0 quake striking 75 km offshore would inflict estimated losses of $75 billion, a massive hit that would ripple throughout Canada’s economy. The New Yorker estimates some seven million people would be impacted in B.C. and the northwestern U.S., including some 13,000 dead and 27,000 injured.

And, in fact, a Magnitude 9.0 quake has happened in that region before, likely in late January 1700.

How do we know? Aside from geological and other evidence, Japanese records speak of an “orphan tsunami” round about that time, large enough to cause minor coastal damage and flooding without anyone feeling a “parent” quake. That’s how large a tsunami the quake sparked.

Europeans had not yet penetrated that part of North America, but Native Americans and First Nations were devastated, with the quake entering the lore of many communities. According to the New Yorker, some peoples tell of whole villages drowned. Others, of tsunamis high enough to leave canoes caught high in the trees.

So if you live in B.C. and your government or business is running you through an earthquake drill, take it seriously. They are absolutely not kidding around.

SOURCES: Earthsky 1 | Earthsky 2 | USGS | Washington Post | International Business Times | Atlas Obscura | USGS | The Guardian | Discovery News | Wired | National Geographic | Science at NASA | Space.com | CBC News | City of Vancouver | Earthquakes Canada | Insurance Bureau of Canada | New Yorker | USGS