150 Sable Island wild horses died last winter, Parks Canada reports

A "severe" but not unprecedented die-off of feral horses on Sable Island last winter reduced the herd by about 25 per cent.

Parks Canada estimates 150 horses died on the remote crescent of sand in the Atlantic Ocean about 290 kilometres southeast of Halifax. That's more than twice the annual average.

Sable Island ecologist Dan Kehler says the horses are most vulnerable in late winter when their energy reserves are lower and grass is harder to find.

"They do carry a parasite load and in the wintertime there isn't a lot of forage for them. So those factors, together with cold, wet, windy weather can create some challenges and lead to mortality," Kehler told CBC News.

He says there have been similar sized die-offs in the past yet the horse population of Sable Island National Park Reserve has continued to grow.

"That's really the best indication of what the consequences of those past actions have been. But no doubt there are some impacts on the genetic structure of the horse population. So you lose probably the weakest individuals, but then again, you have fewer breeding opportunities for the remaining," he says.

RELATED: How the wild horses fared during Fiona

The Sable Island Institute counted the dead horses over a two-week period this summer. Volunteers hiked the dunes searching for the bodies, collecting age and sex data. The results of their survey were sent to Parks Canada.

(Credit: Jewelsy. iStock / Getty Images Plus)

'Correction' from record-high population

The number of horses on the island fluctuates.

Last year, the population reached 591 — the highest ever recorded.

"I would view this as a correction," says Philip McLoughlin, a University of Saskatchewan biologist who has studied Sable Island horses for years.

"It's not unusual for wild populations to go through declines, sometimes severe declines, especially this population which has had a well documented history of going through periods of stable growth and then it declined. It's completely expected," McLoughlin told CBC News.

(CBC)

He says 30 foals were born this summer, and does not feel the herd is in any way threatened.

Since 2007, a team from the university has been naming and tracking the life histories and movements of every horse on Sable Island.

SEE ALSO: New study on Sable Island looks at role of wild horses in ecosystem

Fitter animals likely survived

Last month, he returned from an annual field study on Sable Island.

He says the herd is where it was about eight years ago.

"I would say one of the things we could expect when we look at who survived is that these are likely the fitter individuals. The ones that might be less inbred are the ones that survive. We have to still look at this and it'll be several years before we see how this might have played out."

Parks Canada took over management of the island in 2013, although the Sable Island horses were formally protected in 1961 following a public outcry at a plan to ship them off the island to become work horses or sell them for food.

The horses on Sable Island today are believed to be descendants of animals that were seized by the British from the Acadians during their expulsion from Nova Scotia in the late 1750s and 1760s. A Boston merchant and ship owner who was paid to transport the Acadians to the American colonies also dropped some horses and other animals on the island.

Now Ehler says the horses are being monitored, but must otherwise survive on their own.

"The horses are considered a wild species, so they're protected just like every other species under the Canada National Parks Act. So in general, we let natural processes occur on the island just like we would in another national park."

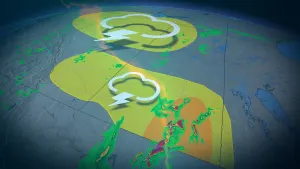

WATCH: How do wild horses of Canada survive our harsh winters?

This article, written by Paul Withers, was originally published for CBC News.